Coyhaique, Chile

The endless dirt roads of the Ruta 40 stretched into infinity ahead of me, winding through dry mountaintops and flat grasslands. The last truck had passed by three hours before – a sheep rancher headed a few clicks ahead to his farm. I turned down the ride; I needed something a little further up, closer to Bajo Caracoles and Perito Moreno. I sat for a time on the side of the road in the deathly silent Patagonian pampa. Then, simply to occupy myself, I began walking north. The high, yellow sun of Argentina’s wild western territories loomed over my head, a brilliant ball of heavenly fire over the empty grasslands and distant snow-capped peaks.

Back on the road. The words send shivers of excitement down my spine. In the days leading up to my departure from Punta Arenas, I was so excited I could hardly sleep. Six months of living in the same place….opening the same door, with the same set of keys. Sleeping on the same bed. Pissing in the same toilet. At first it was a welcome break. But soon, it evolved into just another prison. Presently I had obligations: a job, calling me to the office every morning at seven, errands, bills, phone calls. Then came liberation, in the form of what at first seemed like just another complication…

First, a woman came into my life. The eloquent and sultry T, with her movies and stories and addictive personality. Evey day she was gone felt just a little bit colder and windier than it did when she was there to keep me warm. Then, the administration at work cut my paycheck.

For me that was the last straw. I gutted out the last two weeks at work, picked up my last paycheck for $418.000 pesos, and on the first day of June was back in my natural habitat: on the shoulder of the highway, puffing on a cigarette and scanning the horizon for approaching vehicles. My pack was in the gravel at my feet, and my scarf flapped merrily in the morning breeze.

The first ride came quickly. After less than fifteen minutes of waiting, a red pickup pulled over and the driver motioned for me to store my pack in the bed. I did so, then yanked open the door and hopped into the front seat. I thanked the driver for stopping, feeling my tongue slip back into the familiar routine of hitchhiker-driver small talk. The truck motored slowly off the shoulder of the road, and the tires hummed as they rolled steadily north on the black asphalt of the Ruta 9.

I stole a glance behind me as we drove away; Punta Arenas faded silently into the distance. My home for six months, swallowed gradually up into the uniform tan of the South American grasslands. They say home is where the heart is – at that moment my heart was no longer in Punta Arenas. And so, the Patagonian town of 160.000 dropped out of view and out of my life forever.

And so, that early morning of June 1st, 2011, The Modern Nomad was back on the road once again. His destination? Simple…

North.

Santiago de Chile was the first stop, for there awaited the woman he craved so. From there the plan was, as usual, vague. Just the way he liked it.

______________________________________________________________

There are two ways to get to Santiago from Punta Arenas. The first, and easiest, is to take the Ruta 3 in eastern Argentina to Bariloche, later crossing the Chilean border into Osorno. I had in fact taken this route before; any frequent readers of these stories will remember the jolly, onion-loving Juan, my convivial Chilean trucker friend who drove me across thousands of kilometres of Argentina to Tierra del Fuego back in November. It was, without a doubt, a fantastic memory – perhaps even one of the best rides I’ve ever had. However, due to my yerning to visit as much of the world as humanly possible, I decided to opt for the second, more difficult route…

Ruta 40. A winding, practically unused dirt highway, the Ruta 40 runs from El Calafate in southern Patagonia to the northern border with Bolivia, along the entire western sector of Argentina. It is widely reputed as the most beautiful route in the country, passing through some of the most remote and pristine wilderness the Argentine Republic has to offer.

As some of you might recall, I had explored a little bit of the Ruta 40 before. Back in December I made a foray into Argentina to renew my Chilean visa and kill a few days. After just one day of walking along this desolate yet dazzling dirt track, I knew that one day I would have to explore more.

That day had come.

And so the red pickup motored off towards Puerto Natales. I would get off a few kilometres outside of town and hitchhike my way to the nearby Argentine border, which lay about ten kilometres to the east, passing into the Argentine town of Rio Turbio. My ride dropped me off at the crossroads to the border. I waved farewell and began walking east.

Ah, the feeling! It had returned! The wind was cold, but I cared not. The weight of my new pack on my shoulders, loaded with all my essentials, was a friendly burden; a welcome load which whispered affably into my ear, I am here! You’re detachable other half! Now walk, eternal wanderer! This is what you were born to do!

On I walked. Presently a short ride for three clicks in the back of another pickup took me to the top of a grassy hill, where cows and horses grazed peacefully on either side of a broken fence. A construction vehicle, loaded with earth, drove me the rest of the way to the Argentine border after a five-minute smoke break on my part.

I unzipped my pouch and extracted my passport and Chilean ID card, ready to perform the necessary rituals of customs and immigration. The middle-aged woman behind the counter smiled at me, wishing me a pleasant stay in Argentina and a safe return to Chile, which was according to my documentation, my place of residence. I thanked her, trotted out of the small building, and began walking up the steep hill to the official border between the two countries.

Patches of snow dotted the sparsely forested hillsides. An hour later, after two cars passed me by without picking me up, I crossed on foot the imaginary line which divided Chile and Argentina.

“Bienvenidos a la Republica Argentina,” declared the sign matter-of-factly. Welcome to the Argentine Republic; land of grass, land of mountains, land of jungle. Land of endless, open roads which stretch forever into the vast horizons of the second-largest country in South America. I hiked up my pack and kept walking, the ice on the road crunching grudgingly beneath the soles of my boots.

A car-full of talkative middle-aged woman brought me the rest of the way to Argentine customs, and later, Rio Turbio. Natalinos, on their way to by cheap gas and dry goods from the supermarket, for these things can be bought for half the price in Argentina. I made a stop in the supermarket as well, stocking up on bread, ham, and cheese for the long journey up the Ruta 40 to Perito Moreno.

After lunching on a cold bench near the plaza, I hiked out of town and to the highway leading east towards Rio Gallegos. A quick ride brought me to the intersection with the Ruta 3, heading south one way to 18 de Noviembre, and east in the other to La Esperanza. Expecting a long wait, I prepared myself to be at that intersection for a long time. But it was not to be – after only two minutes, a small black Toyota driven by a woman with straight black hair skidded onto the shoulder and graciously took me in.

And so I met Adrianna, a divorced mother-of-four with a love for travel and a burning drive to live life to it’s fullest. Adrianna chatted my ear off for a good two hours on the way to La Esperanza. I didn’t mind, because she had interesting things to say. She shared a coffee with me in La Esperanza, then zoomed off towards Rio Gallegos.

By this time the Patagonian night had it’s claws hooked deep into the sky, and a tapsetry of stars and constillations covered the freezing emphyrean, with the southern cross hovering in it’s usual place somewhere over Antarctica. I went inside the nearby gas station and wrote a bit in my journal, then began sewing a few rips that had appeared in my brand-new backpack during the day.

The pack was by no means a bad pack; it just had poorly manufactured straps, which were already starting to rip after just one day on the road. I reinforced the tears with roughly fifteen miles of thread per rip, so as to ensure no new strap failures would come to pass during the long walks that lay ahead on the Ruta 40. Around ten, I retired to the back of the gas station and set up my tent about fifty meters behind it, so that the light from the street lamps was not shining into my campsite.

I awoke the next morning around nine to find myself covered with ice. It was everywhere – on my sleeping bag, coated thickly around the inside of the tent, and sprouting flouridly on my pack. My water bottle was frozen solid. I unzipped my sleeping bag (which cracked oddly) and put on my boots, which were also populated with colonies of ice crystals. I pulled myself out of the tent to discover that the entire structure resembled something that had been sitting in a cave in Antarctica for several mellinia. I groaned and began the excruciating task of breaking down camp.

I had lost almost all feeling in my fingers and toes by the time I had shaken the thick frost off of all my gear and packed it back into my bag. I shivered and went back into the gas station to warm my extremities and have a hot cup of coffee. Around ten-thirty, I resumed hitchhiking north to the gaucho town of Gobernador Gregores, which required me to take the Ruta 3 for short period.

Once again a ride was short in coming, a minor miracle for Argentina. The old man passed me by at first, then changed his mind and hit the brakes.

“It’s illegal to pick up hitchhikers, but what the hell!” he said merrily as I placed my pack into the back seat.

Don Juan was 83 years old and from Rio Gallegos. An avid outdoors enthusiast, he told me tales of hunting mountain lions and guanacos in the wilderness of western Santa Cruz. It was a pleasant surprise to talk about hunting, as I hadn’t had many drivers who were too enthusiastic about the activity in the past. I responded with my own tales of hunting illusive 12-point whitetail bucks and vicious wild boars in my homeland of East Texas. Don Juan dropped me off at the crossroads to Piedra Buena.

“Good luck, and happy hunting!” he shouted before he drove off towards Gallegos. I smiled and waved back as his truck disappered into the horizon under the yellow rising sun.

My next ride came after about twenty minutes of walking north. Carlos was a native of Jujuy, in the north of Argentina near the border with Bolivia.

“You’re the first hitchhiker I’ve ever picked up,” said Carlos as he pulled back onto the highway from the gravel shoulder. “I’m not against hitchhiking or anything – I’ve just never seen one before, especially not in this time of year. It’s freezing out!”

I agreed, and told him about the ice. “Gringo popsicle!” he said, giving a colossal chuckle.

Carlos was the owner of a number of semi trucks, and was on a last-minute trip to Piedra Buena to organize a load of rice and beans to Brazil.

“I’ve got six trucks – all from Brazil.” He lit a cigarette and accelerated over a cresting hilltop. “Brazil is the best place to do business, and the best place to buy trucks. They’ve got Macks there, and for cheap.” He pointed at me and said, “Macks are the best kind of trucks.”

Carlos talked more about his business for awhile, then asked where I was from in the U.S.

“Near Houston,” I informed him.

“Houston!” he practically shouted. “I’ve been to Houston, you know that? Yep, went there back in 2006 to take some sort of driving course. Man, that place is hot! It’s hotter than Brazil, and that’s the truth, I swear!”

“It’s a humid heat – the worst kind.”

“That’s it, it’s the humidity. Kills me, and I’m from Jujuy so I should be used to it!” Carlos gave a huge fake pant. “The US Government should declare Houston unfit for human habitation. Miserable! No offense,” he added.

I agreed, but for different reasons.

“Funny story about the airport in Houston,” Carlos went on, “Before leaving Argentina, somebody told me that you can’t buy yerba mate in Texas. Wierd, right?” He didn’t wait for me to answer before going on. “Anyways, so I packed a few kilos in my suitcase for the trip. We arrive to the airport, man, my bag goes through customs, guys in latex are fooling around with it – the whole shebang. Well, one of the X-Ray guys asks me what those kilos of green plants were doing in my bag. I said, ‘What plants?’ Then this big black security guy materializes out of nowhere, (he was a mountain!), and asks me in this deep, big-man voice in English, ‘What you got in you’re suitcase?'”

“Now, I don’t speak much English – none at all, actually. But I got the drift of what he was saying. So I say back to him, ‘Yerba! I’ve got yerba!” He blew out a thick plume of smoke and guffawd.

“Suddenly, four more security guys come up out of nowhere, they’re saying something like, ‘This Mexican’s got three kilos of yerba in his suitcase!’ And I say,’What’s the problem? It’s not illegal!’ Finally, someone who speaks Spanish shows up and explains to them that I meant yerba mate, not yerba marijuana!

“They’re still all suspicious, so they make me open up the kilos and show to them exactly what yerba mate is. After fifteen minutes they still don’t get it, now they think I have three kilos of coca leaves in my suitcase.” Carlos gave a snigger.

“So I have to pull out all my equipment, bomba and all, and prepare a mate for these big fellas!” Carlos cupped his hand around his mouth and shouted to an imaginary waitor. “Garson, hot water, if you will!” He howled with laughter and shook his head. “After that, they were all right – even said it tasted pretty good! Nice guys, after it all was over with. Dumb as posts, though.”

TSA: confusing yerba mate with pot since 2001. Classic.

Carlos left me at the crossroads to Gobernador Gregores an hour later. He shook my hand firmly and gave a toothy grin. “Hey man, drink a mate for me when you get back home, eh? And tell those security guys the next one’s on them!”

“Will do, Carlos. Good luck on your cargo to Brazil.”

“Good luck on your crazy world travel thing! See you later!”

He sped off into the distance, leaving me to walk up the road to Gobernador Gregores, which was dominated by a huge sign that advertised all the Argentine government was doing to improve this route. At least they let you know what they’re up to; in the States, you’re left to wonder what the hell all those bulldozers are doing alongside the highway until finally, months later, some development materializes.

After a brisk hour walk along the mostly deserted highway, an old Mercedes semi pulled over, it’s tires crunching through the salt scattered on the road to melt the ice. Rodrigo was on his way to Gobernador Gregores, taking his load of dirt to be used for the improvement of the upcoming highway.

“Glad to have a little company!” said Rodrigo happily as he downshifted the truck and climbed a small hill. “Here, you can be the mate man – I hate pouring hot water while I’m driving.”

I smiled as I performed the familiar ritual of sipping, pouring, and passing. It’s not hitching in Argentina if you don’t drink 50 gallons of mate with a long-haul trucker!

Rodrigo dumped his load of dirt somewhere along the highway about halfway to Gregores. The huge hydraulic pump raised the tons of dirt as easily as one might pick up a glass of water. “Some days in the summer, we can’t work,” said Rodrigo as he concentrated on the load in the rearview mirror. “That wind’ll catch the trailer and tump it right over!”

We arrived to Gobernador Gregores just before nightfall. Rodrigo dropped me off at the local YPF gas station, where I stashed my pack behind the attendant’s counter, after the attendant promised to look after it. I don’t think I had much to worry about in this tiny town in south-central Patagonia, anyways. I put on my scarf and gloves and set out to explore the town, planning on heading north to Perito Moreno in the morning.

Gobernador Gregores was founded in 1911 for gauchos and sheep ranchers. It’s population in 2001 was 2,000 citizens. However, in 2002, gold was discovered in the surrounding areas, and mines were promptly established, bringing in new citizens from Peru, Bolivia, and the north of Argentina. Now, in 2011, the population was just around 7,000.

I went into the first place that interested me: the library. It was a small building made of red stone. The staff asked me what I was looking for, and I said anything with relatively simple language to help kill a few hours. They recommended to me Juan Sin Rudio, the story of a wild man who lived in the Patagonian pampa and goes on a quest to rescue the beautiful daughter of the Army capitan from savage Red Indians.

I have gotten to the point where I can read books in Spanish, as long as they use simple language and have a lot of dialogue. Juan Sin Rudio was marked under “Juvenile Fiction,” and fit the description perfectly. I was halfway into the fourth chapter when the staff began asking me curious questions. Apparently they don’t get too many outsiders who are mildly proficient in reading Juvenile Fiction in Spanish at their library.

“What are you doing in Gregores?” asked one of the attendants, and I explained to her the whole story.

“That’s incredible!”

“Thanks,” I said. ” So, what can you tell me about Gobernador Gregores?”

“Oh, well that’s a job for Angelica. Wait just a moment, let me go get her for you. She knows everything about this town.” The attendant disappered for a moment and returned a few moments later with a tall woman in her late twenties; this was, apparently, Angelica.

She gave a huge smile and said, “So, what do you want to know about our town?”

“Oh, everything, I suppose,” I replied.

Angelica beamed and launched into a detailed explination on the history of Gobernador Gregores. Founded by the Argentine government in 1911 for gauchos and sheep herders, Gobernador Gregores was most infamous in the Argentine history books for being the site of the Massacre of Lion Canyon, which took place in 1922. Government soldiers slaughtered hundreds of rebelling ranchers in a nearby canyon, shooting down from the ridges at the trapped campesinos below.

“It’s a very sad moment in our history. What exactly happened to provoke the massacre is unclear, as there are very few left alive today who remember it. My grandmother happens to be one of them,” she said proudly. “She told me stories when I was a child.”

“What an awful story to tell to a child,” I said.

Angelica shook her head. “Argentine women must grow up to be strong! Our history is our culture, and our culture is who we are!”

Well-put. “Touché,” I said.

Angelica giggled. “Well, enough standing around here in the library! Let’s go to the kitchen and have some mate! Also, we can smoke in there.”

Now we were talking! Mate and cigarettes! The perfect way to close a day of hitchhiking in Patagonia. We relocated into the kitchen and Andrea continued with her narrative.

“Here in Gobernador Gregores are the strongest winds in Patagonia,” she said as she lit a cigarette and began preparing the mate. “Last summer, they reached 280 kilometres per hour! We couldn’t even go outside, and had to board up the windows or the wind would blow the glass in.” Impressive, and I said so.

“Like I said, we Argentines are strong folk! Any other people would’ve been blown clear across the Atlantic!”

After an hour or so Angelica’s story turned to the history of the library. “You may think I’m crazy when I say this, but this place – hell, this whole town – is haunted.”

“Haunted!” I exclaimed. “By whom?”

She lowered her voice, as if frightened the spirits would hear her. “Well, here in this library, a little girl died a few years ago. During the day, we hear…” she glanced furtively around her, “Footsteps. You can hear them going from room to room. Little pitter-patters, like those a little girl of five or six might make. And I’m not the only one!” Angelica pointed at the other girl whom had given me Juan Sin Rudio. “Vanesa, she’s heard it too! Haven’t you, Vanesa?”

Vanesa nodded. “I was so scared. I told Andrea I would quit if I had to work here alone again.” She shivered.

“Sorry, honey. I didn’t mean to leave you alone,” said Angelica consolingly, patting her knee. “And it’s not just the footsteps! Here, come back here, I want to show you something.” She got up and headed down a narrow hallway to the back of the building. We came to a small room lined with books. In the centre was a padded swivel chair.

“This is the archives room. It’s the most haunted room in the whole building.” Angelica pointed to the chair.

“See this? If you sit in it while you’re alone in the room, she’ll spin it around. While you’re in it.”

“Really?” I said doubtfully.

“Really.”

I was still skeptical. Angelica grinned. “Don’t belive me? Here, sit down, good sir!”

I sat.

“We’ll be back in ten minutes, and you can tell us what happened.” She proffered her pack of Marlboros to me. “Have a cigarette,” she smiled mischievously, “you’re going to need it!”

I rolled my eyes and took the smoke. “We’ll be listening for you’re screams!” said Angelica as she closed the door behind her.

I sat in the chair and lit my cigarette. This is silly, I thought. But at least I got a free cigarette out of the deal. I smoked and stared at the walls around me, which were occupied by ceiling-high bookshelves, packed to their capacity with literature.

Suddenly I felt cold. Not like an outside-cold, but a deep, bone-chilling cold. I looked around me. There was a gas heater a few feet away that was on the highest setting. Strange…

All at once, I felt myself moving. At first I thought it was just the momentum of me moving my arm to drag on my cigarette, but then the chair swiveled a full three inches to the left. As if someone was….pushing it?

I suddenly got a feeling of extreme discomfort. Then the chair moved again, this time a good eight inches to the right.

I definitely didn’t do that.

Fuck this, I thought, and bolted out of the room, slamming the door behind me and sprinting back to the kitchen.

“Hey, you’ve still got nine more minutes!” said Andrea, looking at the clock.

“You win,” I said. “This place is fucking haunted.”

“Told you!” said Angelica triumphantly, and handed me the mate with a smile.

_______________________________________________________________

Angelica told me more ghost stories about Gobernador Gregores until late into the night. Around ten it was time to close the library, and Angelica insisted I let her drive me back to the YPF where I had stashed my pack.

“It’s cold out tonight! Where are you staying?” she asked, starting her little Honda.

“I figure I’ll pitch my tent somewhere. Somewhere far away from the library.”

She laughed. “Well, there’s a good spot on the other side of town near the police station. Ask the officers, they’ll show you were it is.” We pulled up to the YPF and I got out of the car. “Good luck with your travels Patrick!” said Angelica brightly. “And come back soon so we can show you the ghosts in the hospital!”

“No more ghosts,” I said. “But I’ll bring this back tomorrow before I go.” I held up Juan Sin Rudio, which Angelica had loaned me for the evening.

“Just put it in the drop-box, I’ll be with my grandmother on the farm tomorrow.” She waved. “See you around, Patrick!” Angelica revved the engine of the Honda and rolled back towards the town.

I went back inside the YPF and retrieved my bag from behind the counter, which was just as I had left it. I sat down at one of the tables and finished Juan Sin Rudio by two am, then left to go find my campsite and get some sleep. I found it without issues, pitched my tent, and was asleep in minutes.

_______________________________________________________________

The next morning there was more ice, though not as much as in La Esperanza. I packed up camp and started walking out of town, dropping Juan Sin Rudio in the library drop-box and hurrying away from that creepy old building.

Most of the day was spent walking. The traffic was light, but most of the cars that stopped for me were taking a different road to El Chaltén. Around 3 pm a pickup stopped and began driving me north towards Perito Moreno.

My driver was Mauricio, a native of Buenos Aires who worked as a vet in the remote estancias around Gobernador Gregores. “I specialize in sheep and cows.” said Mauricio. “I’ve got all my equipment in here.” He patted a worn leather bag sitting next to him. “This bag’s been in the family for two generations. Made by my great-grandfather, one of the origional settlers of Santa Cruz, in 1886.”

Mauricio filmed practically everything. “One day, I’m gonna splice all my video together and make a 20-year movie about my life,” he said when I asked him why. The vet drove me about fifty kilometres down the Ruta 40 and dropped me off near an estancia named “Santa Thelma.” He made a quick video before driving off.

“This is my friend Patrick,” said Mauricio to the camera, “he’s hitchhiking up to Perito Moreno. I picked him up outside of Gobernador Gregores. Good fella! We talked about sheep and my bag.”

He cut off the camera and we shook hands. “Later Mauricio!” I said.

“Che, ¡nos vemos!” he responded, and hopped back into his truck. The engine rumbled and Mauricio, the vet from Buenos Aires who’s going to make a 20-year movie of his life, faded away into the distance, leaving me alone on the dusty tracks of the Ruta 40.

It was nearing dark and I had forgotten to restock on food in Gobernador Gregores, so I decided to hike over to Estancia Santa Thelma to see if I could work for a hot meal and some water. Upon arrival, I heard voices speaking loudly in French echoing down the gravel road. I approached cautiously.

A man in his early fifties wearing a beret was working sheep’s wool under a small tin roof. The source of the shouts in French were coming from a blonde girl in her mid-twenties wearing a destroyed pair of jeans and covered from head to toe in dirt. They looked up at me as I cleared my throat loudly and said, “¿Hola?”

The girl covered in dirt smiled at me and asked in heavily French-accented Spanish, “Yes? Where did you come from?”

I pointed behind me to the road. “I was hitchhiking.”

“Oh! Very nice! What are you doing here?”

“I was wondering if I could do some work for bread and water?”

The girl gave a neurotic little leap. “Why yes, of course! I was just about to go and make some bread!” She motioned to me. “Come, come, you can help me! Put your pack down over there.”

I did, and we went into a small nearby house with an ancient wood stove burning in the corner.

“I’m Antoinette,” she said.

“Patrick.”

“Very good, Patrick, very good!” Antionette disappered into a small pantry and came out with a sack of flour. “So tell me, Patrick,” started my dirty hostess, “do you know how to make bread?”

“I’ve worked as a baker a couple of times.”

“Great! Let’s get started, then!”

We began kneading the flour, and Antoinette told me the story of the Estancia Santa Thelma. It was owned by the man with the beret whom I saw working the sheep’s wool.

“His name is Jean-Claude, and he bought this place about eight years ago,” said Antionette as she added more water to the mixture. “He found it when he was riding his horse from Tierra del Fuego to Bariloche, and loved it so much he decided to buy it!”

“Wow!” I said, impressed. “Tierra del Fuego to Bariloche on horseback? That’s quite an adventure!”

Antoinette nodded. “He’s published a book. It’s a very good read.”

I imagine so,” I said as I punched the sticky dough mixture, which stuck to my fist and didn’t let go.

“More water,” said Antoinette. I poured more in, and the dough released it’s hold.

“Usually, this is a WOOFF farm,” continued my baker hostess, “I thought you were a volunteer at first! Is that how you found the place?”

“No, I’ve never done WOOFF before. I prefer to do it the old-fashioned way, just passing by and asking. I happened to get dropped off nearby, is all.”

“Very good, very good,” nodded Antoinette as she mercilessly beat the dough. “Yes, I am a WOOFF volunteer here. I have been working at Estancia Santa Thelma for almost three months now. I love it! Life is so simple here. And I’m the only volunteer. Jean-Claude and Maude (his wife) are very choosy about their workers.”

Antoinette and I continued kneading the dough for about half an hour, until there was a knock at the door. In came the black beret of Jean-Claude, followed soon by the rest of him. He looked at me.

“I would like you to chop some wood,” he said, then dissapered back outside.

“You’ll have to excuse him,” said Antoinette breezily, still brutalizing the dough. “He’s really a nice man. Just not very big on words – spoken ones, that is. Better get on that wood!”

I washed the flour off my hands and went outide to the woodpile. There was an old axe laying against a nearby tree. I shrugged, picked it up and split firewood for the next two hours. Later, just before dark, I saw the beret-topped form of Jean-Claude walking out to me. When he arrived, he pointed to the house.

“Dinner,” he said gruffly, then turned and walked back.

Dinner it was, then. I loaded up the split firewood into a wheelbarrow, wheeled it over to the house, and went inside. Waiting for me was a delicious meal of meat and pasta. I ate happily as Antoinette and Maude chatted away in French and Jean-Claude brooded silently into his noodles.

After dinner, I gathered water for the next morning from a small, mostly frozen stream nearby and put it in the kitchen. Antoinette, who was finishing up the dishes, dried her hands off and motioned for me to follow her. We crossed the yard and came to a small building on the other side. Antoinette pushed open the wooden door and switched on the light to reveal two small mattresses.

“This is where the new volunteers usually sleep. I know you’re leaving tomorrow, but we wouldn’t want you to freeze in you’re tent, now would we?”

“Thanks!” I said, and plopped down onto the bed.

“Good night,” said Antoinette as she was leaving. “Oh, and one more thing.”

“What’s that?”

“Are you sure you can’t stay an extra day? Jean-Claude say’s you’re a good wood-chopper, and we’re way behind on our chopping.”

“Well, my girlfriend is waiting for me in Santiago. I should probably stay on the road if I’m going to get there before the world ends.”

Antoinette laughed. “Jean-Calude will be disappointed. But I guess that’s the way things go!” She waved. “Sweet dreams, Patrick!”

“You too, Antoinette.”

Antoinette switched off the light and shut the door behind her. I curled up on the mattress and was asleep in a few minutes.

_______________________________________________________________

The next morning I bid Antoinette, Maude, and Jean-Claude farewell. “Thanks for the bed and the great dinner!” I said.

“Thanks for chopping all that wood,” said Jean-Claude. “You’re a good chopper.”

Antoinette and Maude exchanged surprised glances. As I walked back to the Ruta 40, I heard Maude exclaim,”That’s the most I’ve heard him speak in eight years!” I chuckled and closed the gate behind me.

_______________________________________________________________

And so I walked. The last truck had passed three hours before, headed, as I said, just a few kilometres further up. The sun hovered overhead and a light breeze buffeted the endless patches of bunchgrass. The middle of the Ruta 40 in western Santa Cruz, sixty kilometres north of Gobernador Gregores and about three hundred south of Perito Moreno, where I planned to cross back into Chile to Chile Chico. I walked for another hour when I heard the distant rumble of an approaching pickup. I stuck out my thumb, and who did I see behind the wheel except for Mauricio, the vet with the video camera from Buenos Aires!

“¡Che, Patrick! ¿Como estas? I thought you’d be in Perito Moreno by now!”

“Me too,” I said as I hopped in the truck. Mauricio filmed another short monologue and shook my hand for the camera.”

“What a coincidence, eh?” he said as we drove off into the plains.

Mauricio and I drove for a few hours, passing the icy Rio Chico, which was almost completely frozen over. We stopped for a moment to take some photos and make another video.

“Is this ice crazy or what?” said Mauricio to the camera, who responded by running out of battery.

“Damnit. Don’t worry, I’ve got a spare in the truck!” he said happily, and jogged off to go find it.

Mauricio drove me for another half hour and dropped me off at the crossroads of the Ruta 40 and the road to Perito Moreno National Park. Mauricio made one last video (“Yep, I’m dropping off Patrick at the crossroads here, he’s going to Perito Moreno – the town, not the park…”) and drove off towards the mountains, honking his horn.

By this time it was around three in the afternoon. At first I assumed I was alone at this remote crossroads, until I saw a truck parked on the shoulder about fifty yards ahead. I decided to go and ask the driver if he was headed north, or at least to Bajo Caracoles,the only town in between here and my final destination on the Ruta 40.

The driver was leaned back in his chair and dozing when I walked up. He sat quickly up when he heard me coming, and rolled down his window.

“Yes?”

“Hi,” I started. “I was wondering if you were headed towards Perito Moreno, or maybe Bajo Caracoles?”

He nodded. “Yes, but not until eight pm. I have to stay here until then and count the number of cars that drive by.”

I laughed. “Your job is to count cars?”

He nodded. “Sure is. Easiest job I ever had.”

“How many usually pass by in a day?” I asked, curious.

He yawned, and consulted a clipboard he had sitting next to him in the passenger seat. “Well, today, there’s been…zero.”

Zero? “But it’s 3 pm!” I exclaimed.

“Yep. Not a lot of people take this road.”

“Apparently not.” I thought for a moment, then held out my hand. “My name’s Patrick. I have a feeling we’re going to be here together for a few hours…”

He took my hand and shook it. “Jorge. And I have a feeling you’re right.”

I was right. Between three and eight pm, a total of four birds, five horses, and seventeen sheep had passed by the intersection. “Do you count the sheep?” I asked jokingly.

“Only if there’s fifty or more,” he replied. I laughed.

“I’m serious,” said Jorge.

“Wait…so you’re telling me you’re paid to sit here in your truck on the side of the road all day, counting cars and sheep?” I grinned and shook my head. “How do you stay awake?”

Jorge cracked a smile and pulled out a paper sack from the back seat. “Mate,” he said.

Of course…what else?

_______________________________________________________________

Jorge and I sat there on the side of the road for five solid hours, chatting with each other and sipping bitter yerba mate. Occasionally we would do things to pass the time; Jorge walked around the pampa and looked for interesting rocks to bring home to his daughter in Puerto Madryn.

“The child loves rocks. Can’t get enough of them. I found a blue one last week, she was thrilled.“

That reminded me of a good game I’d invented a few days before, called “Stones,” and I invited Jorge to play a few rounds with me.

“How does it work?” he asked.

“You try to throw the pebbles onto the yellow line,” I said. “You make it, you get a point. You miss – no point. Very simple.”

“All right,” said Jorge, and we began playing. I won the first round, 12/100 against his 6/100, and he won the second (14/100 against my 11/100).

“I guess I learn pretty quick,” said Jorge, tossing his extra pebbles at a nearby road sign.

“We’ll have a rematch later,” I assured him.

The rest of the afternoon was spent basically meandering around and trying to find ways to kill time. I found a sheep skeleton on the other side of the wire fence, and stuck the skull onto a post near the road.

“Sheep repellant,” I said.”Now you won’t have to count so many!”

Jorge laughed, and we played another round of “Stones” as the sun set over the grassy pampa.

At eight it was time for Jorge to leave, and he drove me the 99 kilometres north to Bajo Caracoles.

“Sorry I can’t take you all the way to Perito,” said Jorge. “But my boss will be joining me in Bajo Caracoles, so…you know.”

“I got you. You wouldn’t want to lose such an easy job, now would you?”

“That’s right!” said Jorge. He left me at the only store in Bajo Caracoles and drove off to find his boss.

Bajo Caracoles is so tiny it shouldn’t even be called a town. I’ve seen mining camps with a larger population. Basically, it consists of about 100 people and a loose conglomeration of houses. All the power in the “town” comes from a huge gas generator, which rumbles perpetually on the south side of the homes. The generator was loud and annoying, so I decided to get out of Bajo Caracoles, least I have to try to sleep through that racket. So I switched on my flashlight and began walking north, away from the racket of Bajo Caracoles’ infernal generator.

I walked for several hours into the freezing Patagonian night. Finally, the noise of the generator faded away to nothing, and I was about to turn in for the evening when I heard the sound of an approaching car from the south. I switched my flashlight over the “multiple flash mode” and waved it around as I stuck my thumb into the headlights of the approaching beat-up pickup.

It stopped, and the smiling face of Gabriel the Salteño (from Salta, Argentina) grinned at me through the darkness.

“Come on in, you crazy man! What are you doing out here at night, and in the middle of nowhere?”

“You know. Just walking.” I said as I shut the door and we motored slowly off. Gabriel the Salteño worked for the highway department reconstructing the worst parts of the Ruta 40 in Santa Cruz.

“I can take you up to the encampment about thirty kilometres ahead,” said Gabriel. “I think there’s a guy going to Perito Moreno tonight, so maybe you can hitch a ride with him. Big fat guy, with an ugly goatee. Tell him I said to pick you up.”

I nodded. “I’ll remember that.” Fat guy, ugly goatee, referenced from Gabriel. No problem.

Gabriel dropped me off near the highway encampment and drove off to the lights on the horizon, which were, or course, powered by another clamorous gas generator. I hope Ugly Goatee picked me up, or I’d have to walk all night to get away from that din.

I walked for about ten minutes, then noticed a frozen pond along the side of the road. Despite my preference for warm weather, I am fascinated by ice and frozen things, so I decided to take a break and explore the pond.

It wasn’t very big, maybe two hundred square feet, but it was frozen solid. I ventured cautiously out onto the ice, testing to see if it would hold my weight – it did.

I soon found the ice would hold my weight even in the very middle of the pond. This caused me to become a lot more comfortable, and I skated around with my boots and played soccer with some rocks. This soon became boring, however, so I decided to do what I usually do when I get bored: break stuff.

In this case it was, of course, the ice. I found some big rocks and threw them high into the air, watching them crash down onto the ice and cause gargantuan cracks to form around the impact zone. But no matter how hard I threw the rocks, I couldn’t get the blasted things to break all the way through. Confused, I crawled out onto the ice to try and figure out why.

The answer was soon revealed: the pond was frozen all the way to the bottom! Granted, it wasn’t a very deep pond (maybe two and a half feet), but to a guy from the humid heat of East Texas, that’s pretty damn cool!

I played around at the frozen pond for another half hour and ate the last of the ham and cheese sandwiches I’d bought in Rio Turbio. Then I heard, once again the sound of approaching tires on a dirt road. It must be Ugly Goatee! I grabbed my pack and skated back to the road, flashlight once again in “multiple flash mode.”

The vehicle was coming from the highway settlement; it was Ugly Goatee, all right. He turned onto the Ruta 40 and began heading my way. I waved my flashlight and stuck out my thumb, smile of my face, but to no avail. Ugly Goatee honked his horn and practically ran me over.

Well, that was that. I supposed it was time to make camp. First, however, I could use a hot coffee. I had the powder, but not the hot water, so I ventured over to the highway settlement to find Gabriel and see if I could get some.

I was lucky – the very first trailer I knocked on was Gabriel’s. He smiled and invited me in.

“Sure, crazy man! I’ll put some hot water on!” he said after I asked. Gabriel filled up the kettle and put it on the stove. “You want some food? I made asado!” (Bar-B-Q)

“Sure! Thanks!” I said.

Gabriel motioned to an empty chair next to him. “Take a seat, lokito! You want some wine?“

“Don’t mind if I do!” I said happily.

Gabrial gave me an empty glass and pointed to a box of red wine sitting on the table. “Help yourself, friend!”

I did, and ended up spending a good three hours chatting with Gabriel. We polished off a good three and a half boxes of wine between us, so I was a little tipsy when I said goodbye to Gabriel and headed off into the pampa to make camp.

It was around three am; I was tired, a little drunk, and didn’t care about the noise of the generator anymore. I pitched my tent in a dry creek bed nearby and slept like a rock for six hours.

_______________________________________________________________

The next morning I awoke with a slight headache, packed up camp, and continued my northerly trekking. I walked for a good four hours, stopping once to refill my water bottle in a small stream that wasn’t totally frozen over. Finally, another pickup driven by a silent, hunched over old man took me the rest of the way through uninhabited blank pampa to Perito Moreno.

In Perito Moreno I bought a carton of Argentine cigarettes (since they’re half the price here than they are in Chile), and changed my few remaining Argentine pesos back to Chilean ones. After a brief half-hour wait, I had a ride to the town of Los Antiguos, where I walked 1 kilometre to the Argentine customs checkpoint.

After a half-hearted search of my bag and another stamp on my passport, the policeman waved me through and I started walking to the Chilean checkpoint a few kilometres ahead.

Before I could get there, a small red car with Argentina plates driven by a sour-faced middle aged man pulled over and drove me the rest of the way to the border.

“A gringo, huh?” he said when I told him where I was from. “Do you know what I hate?” he asked me.

“What?” I said, sensing a rant on the horizon.

“I hate the fact that all these American companies think they can just come into Argentina and buy buy buy up all the land. All of Patagonia, they’re trying to buy it all!” He snorted. “Americans. With their companies, and their big business. I hate it!” He slammed hid fist on the dashboard. “Fucking foreigners!” He looked over at me. “I’ll still take you to Chile Chico, though.”

We arrived a few minutes later to the Chilean border checkpoint, where my driver informed the man examining my ID card that “We’ve been arguing the entire ride.”

We were just about ready to leave when the customs agent motioned for me to put my pack on the X-Ray scanner. I did as I was told, and the man scrutinized the screen.

“Whoops,” he said.

“What?” I asked. I didn’t have anything to hide.

“Looks like you’ve got a sandwich in your bag.” He shook his head. “Can’t bring sandwiches into Chile.”

“Why not?” I asked,scoffing slightly. “Sandwiches aren’t illegal in Chile.”

He pointed to the sign above his head, which read “NO PLANT OR ANIMAL PRODUCTS ARE ALLOWED TO ENTER CHILE”

“That’s a cheese sandwich.” He pulled it out and examined it. “Yep, that’s cheese, all right,” he said after a moment’s scrutiny.The customs man handed me the sandwich. “You’re gonna have to eat that before you cross the border.”

“But I was saving it for later,” I protested.

“Too bad. Those are the rules. No plant or animal products allowed in Chile.” He pointed to the sign again.

I shrugged and began eating the sandwich, hitched up my pack and walked to the door. The customs man blocked my way.

“What?” I asked. “I’m eating it!”

He shook his head. “You have to finish your sandwich in here.”

“But my ride is waiting!” The sour-faced old man was looking sourer by the second, tapping his fingers on the hood of his car.

“You have to finish your sandwich in here,” repeated the customs man. I growled and stuffed the rest of the sandwich in my mouth at once.

“‘Dis ‘oood?” I asked around the sandwich.

“You have to swallow it.”

You’ve got to be kidding me. I desperately tried to swallow the load of sandwich all at once, without success. I saw the sour-faced man mutter something that looked like “fucking foreigners with their contraband” and bang his fist on the hood of his car. He muttered for a second longer, than got back in the driver’s seat, slammed the door angrily, and drove off.

I swallowed the rest of my sandwich. “Thanks. Now I have to walk to Chile Chico.”

“No plant or animal products are allowed into Chile,” quoted the customs man, pointing again at the sign above his head. I muttered a veiled obscenity and went out the door.

“No plant or animal products are allowed in Chile!” I heard the customs man shout from behind his X-Ray machine.

“So I’ve heard,” I called over my shoulder, then walked the three kilometres to Chile Chico.

_______________________________________________________________

Chile Chico was having a good day when I arrived. The bright sun peeked out from amongst streaking white stratus clouds behind a foreground of rocky islands sitting serenely in the crystal-clear Lake General Carrera. Despite the foolishness at customs, I was, as usual glad to be back in Chile. I spent the evening checking emails, then hiked to the small, rocky hill surrounding Chile Chico and made camp for the evening.

I awoke the next morning as early as possible and began trying to hitchhike to the nearest notable town, Coyhaique. However, the road leading out of Chile Chico is, like the Ruta 40, extremely low-traffic. I spent most of the morning walking along the deserted yet stunning road to Coyhaique.

Finally, around two pm, a pickup (that seems to be the only type of vehicle that travels on these deserted roads) drove me about thirty kilometres further into the middle of nowhere and dropped me off by a gold and silver mine.

I waited there for another three hours, when finally a passing bus agreed to take me for free to Puerto Guadal, a microscopic town on the southwestern shores of Lake General Carrera. When we arrived it was dark, so I bought some more bread, ham, and cheese and set up my tent on the lakeshore.

The next morning I arose at 5 am, determined to make it to Coyhaique, as T was waiting for me in Santiago so we could go to the hot, dry deserts of the north for a month of arid relaxation. I had already been on the road a week, and had figured I would be at least to Puerto Montt by now.

It was raining when I woke up. I made a sandwich and smoked a cigarette in the downpour as I waited for a truck to pass and take me a little closer to Coyhaique, still 250 kilometres to the north. Around eight a pickup drove me about ten clicks to a crossroads, where I waited for another five hours, playing “Stones” and drying my gloves on a thorny berry bush during occasional breaks in the rain.

Finally, around 3 pm, my ride to Coyhaique came. My driver was…American?

Johnathan was from Evergreen, Colorado, but had lived in Cochrane (a small town a few hundred kilometres to the south) for fifteen years.

“I first came to Chile to live a childhood dream, which was to explore the frontier,” said Johnathan. “I arrived to Aysén for the first time when I was nineteen, and knew immediately that this was the place I’d been dreaming of. So I came back two years later with $8.000 dollars, bought myself a whitewater raft, and started my own adventure tourism company.”

Nowadays, Johnathan’s company had grown considerably from it’s humble beginnings. “Fifteen years later,” he continued, munching on homemade trail mix, “I run fifteen-day expeditions on the Rio Baker, and twenty-five day expeditions along the ice caps. I usually spend about…200 days a year in the field.” He grinned through a mouthful of granola. “I couldn’t be happier!”

And Johnathan wasn’t just a successful proprietor of what he called “torture tourism” (“You learn everything you ever wanted to know about yourself with me…the hard way!”) – he was also leading the charge against one of the most controversial issues in Chile today: HydroAysén.

HydroAysén is a project currently being developed by the Chilean government to dam some of Patagonia’s wildest rivers (including the Baker, Johnathan’s rafting haunt), in order to generate hydroelectric energy…for the extreme north of the country.

“It’s not just the dams,” said Johnathan angrily, “although that’s a major part of it. It’s the fact that they’ll have to run high-energy power lines 3.000 kilometres to the north of Chile where the electricity is needed!” He shook his head. “It’s the most shamelessly destructive energy project I’ve ever seen.”

But Johnathan wasn’t going to let the Rio Baker, and with it the wilderness he lived for, go down without a fight. “We’ve made a powerful documentary film, called Patagonia Rising, about the seriousness of the impacts this project will bring about. It premires tomorrow in San Fransisco, and hopefully sometime this month in theaters all around Chile.”

Powerful stuff. I wished Johnathan all the luck in the world in his charge against the development of the wilderness, for I hate HydroAysén just as much as the next person in Chile. As we neared Coyhaique, Johnathan made phone calls to the promoters of his film, trying desperately to get it shown in as many places as possible. I hope with all my heart that his project will succeed – the destruction of a wilderness as pristine as Patagonia is indeed an ugly thing. I ask any and all readers here to visit the website I’ve linked to and do all you can to support Johnathan in his crusade for Patagonia.

We passed through a snow-covered mountain pass and soon were in Coyhaique. Johnathan summed up Coyhaique pretty effectively in just a few words:

“60.000 people, 50.000 wood-burning heat sources,” he said with a scowl. And he was right. When I got out of the truck in Coyhaique, I smelled the strong, distinct smell of burning firewood. The entire city smelled like a Boy Scout camp.

Johnathan dropped me off near a service station in the downtown, and we shook hands goodbye.

“Good luck in Santiago,” said he with smile.

“Good luck saving Patagonia!” I replied, and we parted ways.

_______________________________________________________________

I arrived to Coyhaique yesterday evening, and spent most of the night hanging around gas stations and trying to bum a ride out of here. This morning I got a guy to agree to take me to Puerto Montt vía the ferry from Chaitén, but when I went to our agreed-upon meeting place just and hour ago, I discovered that he had bailed on me. An entire day, wasted. T is going to kill me…

So tomorrow I’ll set out walking, to Chaitén or bust! and somehow make my way to Puerto Montt through the confusing mix of muddy roads and ferries known as the Carretera Austral.

It’s going to be a long, wet next couple of days…

Until next time, my friends!

-MN

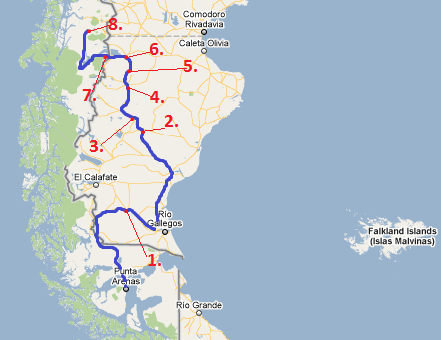

1. La Esperanza 5. Highwaymen’s Encampment

2. Gobernador Gregores 6. Perito Moreno

3. Estancia Santa Thelma 7. Chile Chico

4. Bajo Caracoles 8. Coyhaique

Patrick,

Great entry. You know maybe it’s me. I’ve never gotten a long haul trucker to pick me up in the States. Only Mexico. But mine did not consume Mate. I love the stuff personally. He had small capsules of “Perico”, which as you know is Cocaine….

But still one of my best rides. Man I dig reading your entries.

Buena suerte amigo!

Igualmente compadre! Que te vaya super bien, hueavon!

-MN

I love the comment “T is going to kill me” because in fact, it’s going to be like that ahahahaa

I didn’t get the same experience than you with the Customs in Chile Chico; they cared (maybe too much) about me, proposing me food, drinks of any kind, and even “a bed” into their “residence”. They added that when they had special guests they had a lot of fun… Yuck, I was so disgusted I paid for a bus to get away from them and to go to the centre of Chile Chico!

Also it’s interesting to see we did the same road but didn’t see the same things, on the Argentinan side, from Perito Moreno to Los Antiguos there were some particular hills ;

The first one was on the left side, it’s called El indio parado, and in fact, the rocks look like an indian standing and looking at the road. On the other side of the Buenos Aires Lake, there was a Pyramid hill, perfectly made. Not far from it, “Cerro Castillo” with its donjon and towers, incredible!

In fact, 1h before on the road to Coyhaique you can go to the town of Cerro Castillo, I stopped there a couple oh hours to see the Prehistoric paintings on a huge stone wall…

It’s a shame I didn’t stay longer on this part of Chile Chico, the whole area has a lot of history.

The pueblo Los Antiguos has this name because this is where the old indians were sent to live their last days as the lake offers to Los Antiguos a local microclimate…

I ll show you the pics later, if you happen to arrive soon :-)

wow is all I can say, it’s such an exciting thrill to read. Totally consumed into your adventure and wouldn’t leave before I hit the last line; and even then, I had to comment to let you know how great piece of writing you are doing!

May the force be with you my brother from another mother…

Customs agents confusing mate for drugs. I would have so much fun with that, although with less than stellar English that could be frustrating. Really love your writing it is incredible, so you really don{t need photos. Good Luck in your travels!