Las Lomitas, Formosa, Argentina

Las Lomitas is a humid, sweltering town in the north of Argentina near the border with Bolivia and Paraguay. Tony and I now sit in a small service station on the western outskirts of town, where we’ve met Maxi, a breath of fresh air and friendliness after two long, hostile days of hitchhiking and walking down the Ruta 81. Our sights are set on Misiónes, a further seven or eight hundred kilometres to the east. As per to my previous experiences hitchhiking in northern Argentina, the going has been decidedly slow since traversing the Andes from Chile. It’s now been nearly five days since we crossed into Jujuy from San Pedro de Atacama vía the long and infamous Andean pass known as Paso Jama, and since then we’ve only managed to slug our way down less than 200 kilometres of sweltering asphalt per day. Once again, welcome to Argentina – hitchhiker’s hell.

I will, of course, start this story from the beginning, which in this case is eight days ago in Santiago de Chile. Tony and I awoke very early at his home in Las Condes in anticipation of the long day of waiting that hitchhiking out of Santiago inevitably brings. We jumped on the first metro train of the morning (leaving at 0545) and came out of the Vespucio Norte station just as the sun was rising up above the frigid mountain capital city. The air was cold and the rays of the rising sun made intricate red and blue lines in the cloudy morning sky. We breathed in huge gulps, and I felt the familiar nervous anticipation that an impending long hitchhiking journey never fails to bring me. After a bit of wandering Tony and I managed to find the bus that would take us to our good hitchhiking spot (which, for anyone out there who wants to know, is bus number 425. Write that down, I should have). We got off in the same spot T and I had nearly three months before, and prepared ourselves for a long wait.

The morning was cold and there was a biting wind whistling down the Ruta 5; our fingers and other extremities froze and became hard to move as we thumbed at semi after semi roaring north. For a pair of strapping young men like ourselves we expected to possibly wait all day long, but luck was with us, and stayed with us for the rest of Chile before mysteriously abandoning us somewhere in San Pedro. A small truck pulled over after only about an hour of waiting and drove us twenty or so kilometres further north, which was enough kilometres for us to be officially out of Santiago and usher in periods of good, easy hitchhiking.

Soon after being dropped off an old couple in a small car stopped for us and drove our relived bodies a few hours towards the Atacama, leaving us at a popular truck stop near the coastal town of Los Vilos. The resturaunt did indeed seem a popular stopover for truckers of every kind, and I wondered why I hadn’t been to this spot before, as I had found myself hitchhiking north from Los Vilos on at least two previous occasions.

The spot proved successful, and a trucker stopped after a very short wait and, after stopping a few clicks further north for a shower, drove us all the way to La Serena. By the time we arrived it was near dark, so Tony and I decided to make camp for the evening. The trucker had dropped us off near the northern outskirts of La Serena near a supermarket complex, to where he had been delivering a load of dry goods from Santiago. We found a nice, secluded spot with a couple of trees behind the supermarket and made camp there. I hung my hammock between two trees and Tony set up his sleeping bag and bedroll on a flat patch of ground nearby, as he had yet to purchase a hammock for our upcoming time in the jungles of Brazil and Guyana.

After a quick trip to the supermarket on my part to buy some bread, ham, and cheese to use as provisions for the next few days, we said our goodnights and were out like two lights, Tony snoring in the dirt and myself still swinging slightly back and forth in my hammock. The next morning we awoke to the sound of Tony’s cell phone alarm ringing; the loud classical music cut sharply through the morning sea fog of La Serena and Rachmaninoff blared us out of our dreams and back into the Coquimbo region. We quickly packed up camp and walked to the best hitchhiking spot I knew of out of La Serena, refilling our water bottle at a few roadside fruit stands. The owner of one of the fruit stands kindly gifted us a few papayas to eat as we waited for our next ride north.

That ride came as I was brushing my teeth with our water and my old red toothbrush – Miguel, a trucker from Santiago and vibrant, enthusiastic conservationist drove us as far as about fifteen clicks south of Vallenar. From there we walked, and walked, and walked some more.

The highway leading out of Vallenar had changed some since I had last been there a few months before; the road was under construction, and the workers had put up a very inconvenient barrier on the right side of the road, leaving no shoulder and hence, absolutely no place to stop for anyone who might care to. So we walked in the burning desert sun, nearly six kilometres, until the barrier gave way and the road was equipped with a shoulder once more.

Tony was still getting used to walking with a heavy load on his back (and on top of that he was carrying a violin for busking), so after our trek he was decidedly famished. My Padawan learner rested, drank water, and still managed to stay on his feet to hitchhike with me. Another trucker soon pulled over and offered us welcome relief from the dry desert heat of the Atacama.

George was loud and obnoxious, though not so much to the point where you didn’t like him. Nearly every sentence was littered with at least three swear words, but the booming and jolly way he delivered them never failed to make us smile. He did, however, upset me once. As I was explaining to him my history in Santiago, George asked me about T. I told him all about her, and how she was still a very important person in my life. Our trucker friend thought this just dandy, and asked if he could call her to say hello. I told him sure, (T is very fond of truckers, after all), and I figured she would appreciate some contact with the road as she worked in Santiago.

This proved to be a mistake. George dialed the number I gave him…

“Hello? Hello? T?” he bellowed. There was a muffled reply through the line, which was, apparently, T.

“It’s your friend, George!”

More muted replies.

“Hey, when can I come to see you?”

You can probably guess where it went from there. Using the information I gave him, he was able to sufficiently freak T out and cause her to have to later change her number. He never identified himself as my driver, only expressing interest to meet her. That surprised and rather upsetted me, though I didn’t let it show. I believe T is still a little angry with me for that one.

Anyways, George was on his way to a toll booth under construction just twenty clicks south of Copiapó, on the hunt for some large construction bulldozers to haul back to Santiago, their usefulness having run out at the shiny new collector’s booth. After a short 40 minute ride we arrived and George drove off to look for his bulldozer bulldozer. Tony and I waited in the shade of an overpass while we ate the last of our cheese from La Serena, which was sweating more than Uasian Bolt after the 200 meter dash.

There were a few construction workers just ahead of us stopping traffic with a little stop-go multi-function sign so that a piece of heavy machinenary up ahead could do some mysterious job involving a lot of raising and lowering of the entire vehicle. When traffic piled up behind the worker, Tony and I of course thumbed at the cars stopped there. I was surprised and amused to find that my Padawan learner didn’t take no for an answer; when I hitchhiked in these sort of places, I gazed sweetly at the driver and held out my thumb hopefully. If the driver shook his head no or ignored me, I put my thumb back down.

Tony, however, was a different story. He would hold his thumb out and fix the driver with a dead stare for the duration of the car’s wait time, until the construction worker would let line of cars pass and the driver looked fearfully at Tony in his rearview mirror.

After twenty minutes of waiting, our savior arrived. Driving a big blue semi, Hugo pushed open the door and welcomed us into a ride that would last the better part of 36 hours – first to Antofagasta to drop off a load of frozen poultry, and the next day to Calama. As you can probably imagine, we felt immense relief for such a long lift, so we paid back what we could in interesting conversation, which Hugo seemed to enjoy greatly –particularly Tony’s condensed version of the ancient Chinese tale “Journey to the West,” which my Taiwanese-Chilean friend recounted in vivid detail using top-notch Castellano Chileno. The story was so long that it probably took 200 kilometres of driving to tell – in it’s extremely condensed version.

“…and so,” said Tony, “since he had failed Buddha’s test, Sun Wu Kong was sentenced to 500 years of imprisonment in the mountain, finally pacifying (for the time being), the Monkey’s God-angering antics on Earth.”

“Could the Monkey still fly and transform into monsters?” asked Hugo.

“Yes. But When Buddha wants someone to stay in a mountain for 500 years, that person stays in a mountain for 500 years.” Tony grinned. “Anyways, that’s the end of chapter three.”

Hugo gave a throaty chuckle. “Those Chinese stories sure are crazy! That Monkey was causing all sorts mischief. ¡Mono culiao!”

“Mono culiao, indeed,” agreed Tony.

As the epic tale of the Monkey wound to an end and finished with a life lesson (typical Chinese, I love it), we stopped around nine at a posada (remote truck stop) to prepare what is known in Chile as “once.” Once in Spanish means eleven, and it’s what Chileans use to refer to the last meal of the day – usually bread, ham, cheese, and a coffee or tea. Hugo came prepared with bread and huge chunks of meat, and we boiled water for coffee on his portable stove while dining upon probably the biggest once sandwiches I’ve ever had the pleasure to chew in Chile. ¡Que rico!

We arrived to Antofagasta around one that morning, and Hugo left the truck parked in front of the chicken place while we went to sleep. We were now waiting for the workers to arrive and begin unloading the cargo, which supposedly would take place sometime around four that morning.

Four in the morning came and went, and as I dozed rather uncomfortably in the passenger seat Tony and Hugo snored rackets from the bunk bed behind me. Finally, around eight (“…four hours late,” commented Hugo irritably), the workers finally showed up and unloaded the frozen fowl while our trio went for a light breakfast nearby.

Nine a.m. saw us bound for Calama at last; Tony and I were visibly anxious to hitch to San Pedro (our last stop in Chile) and get over to Misiónes and Brazil at last. Hugo dropped us off in a couldn’t-be-more-perfect spot right next to the giant statue of the Virgin Mary which marked the turnoff to San Pedro. Our ride from there came more quickly than I thought it would; while I was releasing pent up energy and digested food behind a large, craggly rock twenty or so metres from the highway I heard Tony shout to me “Come on man, we’ve got a ride!”

I excused myself to the driver who saw me quite obviously buttoning up my pants and stashing the toilet paper back away as I ran up to his truck. “When nature calls…” I said, shrugging. He laughed and drove us very quickly to San Pedro.

—————————————————————————————————

For someone who really doesn’t care for San Pedro, I found ironic that I found myself there for the fourth time in less than two years. Of course, this time (like every other time but one) was out of necessity. You’ll remember that the three other times I went to San Pedro, one was to enjoy it with T and the other two were to cross either Paso Sico to Salta or to sneak into Bolivia off the side of another pass to Argentina. This time was once again a necessity: I and my intrepid Padawan learner were bound for Jujuy across the entirety of the notorious Andean mountain pass known as Paso Jama.

Paso Jama is no cup of tea; more than 200 kilometres long, it’s first 100 kilometres are pure 45% incline, making it a real gas-burner for both truckers and trekkers alike. The rest of the road winds through frigid altiplano before coming to the Argentine border control. Even though the actual border of Chile and Argentina is a further 200 kilometres up the road from San Pedro, travellers wishing to take this exit route out of Chile must first pass through immigration and customs located on the outskirts of the town.

Unfortunately, there are some complications if you’re looking to hitchhike to either Salta or Jujuy from San Pedro, and these complications stem from, as is almost always the case, the local authorities. In San Pedro, if you wish to cross any of these international passes from San Pedro, you may not simply take care of your paperwork, cross on foot, and hitchhike on the other side, as is the case with every other border with Chile and Argentina in my experience. Due to the remotness of the route, all travellers must have at least a bicycle in their possession with which to cross the border. The customs agents will not allow you to cross by hitchhiking, at least not in the old fashioned sense of the word. The only legal way to hitchhike across either Paso Sico or Paso Jama is by organizing a ride beforehand, which due to the international nature of the road ahead, is no easy task.

Now, I probably should have known this fact by now – after all, I had crossed this border twice in the past. But then, even though I’ve crossed it twice, both of the times I did so were done illegally, so there was no way of knowing about this extenuating circumstance at the San Pedro de Atacama Immigration & Customs.

Tony and I weren’t able to find anyone to drive us across to Jujuy that day, so we resigned ourselves to camping in the desert for the evening and giving it a fresh go in the morning. We walked about twenty minutes north from Immigration and made camp in the form of two sleeping bags rolled up in a tarp on a swath of dry ground we had cleared of large, uncomfortable stones.

Once again, Rachmaninoff woke us up bright and early, so we began our hunt for a trans-border trucker just as the border was opening up for the day. Our last shred of Chilean luck was cosmically spent on the jolly bearded face of Antonio the Paraguyan trucker, whom agreed to take us to Jujuy with almost no hesitation whatsoever.

“Can you speak Guarani?” I asked curiously as we waited in line at customs.

“In Paraguay, we speak Guarañol – a mix between Guarani and Spanish.” He chuckled. “No, not too many can speak pure Guarani, except for some of the people in the countryside.”

After taking care of all the paperwork we hopped into Antonio’s old, decrepit big rig towing a trailer of old Korean cars to Paraguay from the Zona Franca in Iquique. After stopping for a moment to prepare a mate and some breakfast, we began the long, slow decent up Paso Jama. After about three hours we made it to the highest point, situated at more than 5,000 metres. I could already feel the altitude destroying my lips as Antonio made Paraguay, with its tropical lowlands, sound extremely inviting to us.

“It’s easily the best country in the world,” said Antonio dreamily. “Paraguay, el corazón de sudamérica, will always be the best in my heart.”

“We would love to visit,” I said. “Only problem is, Paraguay charges me about fifty dollars to get in, so I haven’t yet had the opportunity to visit.”

Antonio looked at me strangely. “Paraguay charges you money to enter? Even though you have a Chilean ID card?”

Hm. I had never thought of that. Perhaps I could enter Paraguay with a Chilean card (Chileans get in for free and can travel with only their ID card in most South American countries).

“That’s a good idea,” I said animatedly. “I should give it a shot!” I took out my Chilean ID and examined it. “But…it does say, ‘Nationality: USA’ on the front, so I still might have to pay.”

Antonio shook his head. “Paraguayan customs are not very thorough even on their very best of days. I’m sure you’ll slip by without any problems.”

I filed that little tidbit of information away under “useful to know” as we continued climbing and talking.

“If you come to Paraguay, I invite you to my home. You can stay and teach English to everybody, and Tony can teach Chinese!” Antonio grinned widely. “There are a lot of Taiwanese in Paraguay, you know. Some parts of Ciudad del Este are like ‘Little Taiwan!’”

Tony found this surprising, and we decided that we would have to try and go to Paraguay and see this for ourselves before going all the way up to Guyana. Perhaps a trip to Paraguay was in the future sooner than initially imagined.

Around three pm, the semi began making a loud bubbling sound, so Antonio pulled over smack-dab in the middle of nowhere to see what the problem was.

“It’s probably just the radiator overheating,” he said as he opened his door and climbed down. “That climb up from Chile is really hard on the motor.”

We got down and peered into the engine. Antonio examined seemingly random places around the motor and made disapproving clucking noises as Tony and I stared at the same places and pretended we knew what the hell it was we were staring at. The inside of a big rig is a complicated place; I can change a tire, but anything more than that is a mystery to me. Tony is even worse; I don’t think he can even do the tire.

“Yep, it’s the radiator,” said Antonio, nodding to himself. “We’ll have to give her some time to cool down and pour cold water inside.”

Tony and I fetched the gallons and gallons of cold water Antonio had brought with him from San Pedro and poured it into the radiator under the trucker’s supervision. Soon we had used almost all the water, yet the radiator was still boiling. Finally, after a good hour of seemingly futile cooling attempts, the damned thing seemed pacified and cooled down; we sat on the asphalt and drank Paraguayan mate mixed with medicinal herbs while resting from the exertion of all that water-pouring. When we finally got back into the truck, Antonio suddenly made an angry, surprised noise as he peered at the numerous gagues and knobs on the dashboard of the semi.

“La puta madre…” he breathed. “The compressor’s gone out! Now the trailer has no brakes!” The trucker opened the door and immersed himself with taking apart the compressor, which is apparently located right near the gas tank. Interesting.

Antonio fiddled and tweaked the compressor for at least two hours, to no avail. He even had a few other Paraguayan trucks stop and try to somehow boost his compressor with air from their trucks, but that didn’t work either. As Tony and I weren’t much help when it came to compressor work, we went off into the altiplano with a couple of large, empty jugs in search of more water for the semi.

“Looks like there’s a lake over there,” said Tony, pointing vaguely to the west.

“Looks pretty far away to me,” I responded, looking at the thin strip of blue in the distance. “But, I suppose we’ve nothing else to do. Let’s go!”

So we walked. Unfortunately, after about fifteen minutes of hiking, the lake did not seem to be getting any closer. Then a thought came to me; altiplanic lakes were usually very shallow, even less than an inch deep. It would be difficult to fill these large jugs in such a shallow lake, so I sent Tony back to the truck to find some smaller bottles for scooping while I continued to our potentian water source. Fortunately, after clearing a ridge a couple of minutes later, I spotted a small lake situated at the bottom of a canyon that was much closer. I walked down the steep incline and located a couple of disguarded small coke bottles laying on the lakeshore, no doubt left by other stranded hitchhikers looking to get water for their radiator-challenged Paraguayan big rig.

As I had predicted the lake was quite shallow, so it was good I had found the empty soda bottles on the shoreline. The water around the bank was black, muddy, and partially frozen. Not good for radiators, I imagined, so I took off my boots, rolled up my pants past my knees, and waded out into the middle of the freezing lake to get some cleaner radiator-coolant.

I had almost finished filling the second jug when I spotted Tony up on a distant ridge, looking rather lost and carrying a few more water containers. I shouted and called for him to come down to the small lake.

“I thought for sure you had gone to that big lake in the distance,” he said as he arrived.

“Plenty of good water here,” was my response. I waded over in the inch-deep lake through three inches of black mud and took some of the smaller containers from him and filled those too. After all was said and done, we had about seventeen gallons of water to haul back to the semi back on the road about two kilometres away. The first step was to climb the ridge leading out of the canyon in which the small lake was situated. My Padawan and I distributed the weight evenly between us and began the climb.

The air at this altitude was extremely thin, and since I had passed a lot of time before in this sort of climate I adapted quickly. Tony, however, was a different story. His lungs were used to the jungles of Taiwan, and I think the highest altitude he had visited was back in Santiago. Here, with four or five times more altitude, he was not doing too well. He asked to stop and rest several times, and finally, about two-thirds way up the ridge, I took about fifteen gallons of the water and left Tony with only two. Still, his slight Asian frame was having trouble with even this. I couldn’t blame him, though; climbing a ridge in the altiplano can be an arduous ordeal even at the best of times.

Fifteen gallons of water is very heavy, so I walked as quickly as I could up the ridge and left Tony behind with the last two. Once I had cleared the ridge I rested for a moment while my friend caught up, then set off once more down the slope towards the semi. There were still about a kilometre and a half to go and one smaller ridge to climb, so I walked quickly and took only a few ten-second breaks until I got back to Antonio. I filled the big 55 gallon drum on the trailer with the fifteen gallons and went to check up on Antonio. Still no progress, he told me. We were going to have to stay the night.

When Tony dragged his tired body up the last ridge to the semi and added his two gallons to the big blue plastic drum, I broke the news to him.

“Man, we are going to be cold…” he said, after catching his breath.

And he was right.

————————————————————————————–

Since the cab of the big rig had been jacked up to provide easier access for Antonio’s mechanical escapades, we would be sleeping in an old Korean van that was on the trailer. After siphoning some gas into the engine so we could leave it running and get some heat into the vehicle, Tony crashed out in the backseat while I watched a few movies with Antonio on his portable DVD player. Around ten thirty, I followed Tony’s example and went to sleep as well.

When I awoke the next morning, I became extremely alarmed. My hands and feet were missing! Where there had before been perfectly lively extremities, I felt only air! Someone had removed my hands during the night!

I sat up in a panic, only to realize that no-one had actually cut off my hands and feet whilst I slept. My hands and feet were merely frozen, and I could hardly feel them at all. I rubbed the feeling back into my joints and wondered where all the heat from that quarter tank of gas we’d siphoned the night before had gone. Tony was in similar states of distress over his frozen fingers, and we wondered just how cold it had gotten while we slept. We later learned that it had been around -25°C. With wind. How horrific.

As Tony and I were waking up Antonio boiled a little bit of water for coffee with his portable stove. Later, as we were mixing our brew, Antonio called out to us that he was going to get help. This would be the last we saw of him.

Antonio did not tell us exactly where he had gone to get help, and after an hour or two of freezing and more freezing, we decided to hitch onto the next truck that passed and continue on without him. After all, who knew how long it could take to repair that compressor? A passing Chilean trucker quickly agreed to take us as far as the Argentine checkpoint ahead, and he left us there while we went inside to take care of the paperwork required of us for entry into Argentina.

More borders, more problems, at least that seems to be the case for me since I have a habit of sometimes crossing them irresponsibly. I walked up to the fat, toad-like woman behind the immigration counter (that seems to be the standard shape for Argentine immigration officials) and cheerfully presented her with my Passport.

“What are you travelling in?” she asked, staring at me from over the top of her Far-Side narrow glasses.

“In a daze,” I replied, still smiling.

Toad Woman did not return my smile. “Car? Bicycle? Semi-truck?”

“We’re hitchhiking.”

Toad Woman sighed. “In which vehicle are you travelling in? Where is the driver?”

“He left us to go and get help somewhere. Truck broke down.”

“Then how did you get here?”

“We hitched onto another truck.”

“And where is that trucker now?”

I shrugged. “Probably on his way to Jujuy.”

Toad Woman snapped shut my passport and handed it back to me without stamping it or entering anything into the computer.

“You must find a driver here who is willing to take you at least to the closest town,” croaked T.W. “Now please,” she glared through her spectacles, “get out of here.”

Just like in San Pedro, we would need to find a trucker who would agree to put our names on his official international paperwork in order for us to be allowed to continue into the Argentine Republic. Paso Jama, how damned inconvenient you are.

Thankfully, after only a few duds an Argentine trucker finally agreed to take us as far as Jujuy. Manuel from Salta cheerfully did his paperwork with us; Toad Woman stamped my passport, told me I had 90 days to spend in country, and just like that we were finally stamped into Argentina, all trussed up and official-like. As we drove through the arid Argentine altiplano, we chatted with Manuel about topics such as spending money and soccer. Manuel had made numerous trips to Chile, but the one thing that seemed to confuse him most about the country were the strange words Chileans tend to use for everyday things.

“So I was stopped at a police checkpoint this one time,” said Manuel through a mouthful of coca leaves, “and the fella asks me, ‘Excuse me, have you seen un gallo y una cabra passing by on a motorcycle?” Manuel threw his hands up in confusion and laughed. “Now, what a sight that must be! Who is driving – and most importantly…how?”

Allow me to explain the humor of the situation: In Chile, the word gallo is widely used to describe a man. Literally, it means rooster. Cabra, Spanish for nanny goat, is also often used to describe a woman. So now you can understand poor Manuel’s confusion when he heard a serious police officer asking him directly if he’d seen a rooster and a nanny goat driving by on a motorcycle. Chile is often very hard to understand for those who have not spent any time there – mostly for the crazy way Chileans like to talk. It’s some looniness that I’m going to miss in my upcoming time away from the country – though learning Portuguese is sure to be interesting.

We slowly descended from the highlands, and at one point took the curviest, most treacherous descending roads I had seen in my entire life. The last decent took us into what seemed to be empty, white space. As the truck dipped lower and lower, the details of the lowlands began to slowly take shape. Fields, houses, and most importantly, green. No more arid Atacama for us! When we finally arrived to Jujuy around three pm, I asked Manuel how far it was to the Ruta 81, which was the road we needed to take to Formosa and eventually, Misiónes.

“The 81 does not leave out of Jujuy,” said Manuel, shaking his head. “First, you have to go to Perico and take the 34; from there follow it for about 200 kilometres. The Ruta 81 starts later in a small town called Embarcación.”

Then to Perico it was! Manuel dropped us off at the exit for the town about 20 kilometres south of Jujuy and continued on to Salta with a wave. Meanwhile, Tony and I hiked the two or three kilometres into Perico for some much-needed food and water.

Since coming down from the altiplano, the climate around us had changed dramatically. Now, instead of freezing highlands, we were in the sweaty, hot, and extremely sunny subtropical lands of northern Argentina. Mosquitos buzzed and small motorcycles populated most of the avalible roadside parking spaces. The South American sub-tropics at their very finest.

Fortunately, I had managed to change $5,000 Chilean pesos for fifty Argentinean pesos at the border with Manuel, so after wandering about for an hour or so (it was Sunday and everything seemed to be closed), we finally found a small outdoor sandwich place that was open and showing a soccer match. There was a large group of people gathered around the TV paying absolute attention to the events that were happening onscreen.

I ordered two sandwiches for twenty pesos and as much water as we could hold. As we sat, an old gentleman who was very drunk took quite a liking to Tony and began chatting up a storm with him. After awhile, Tony asked his name.

The old man snorted drunkenly. “Why d’ya need to know my name, eh? Well, if you insist, you can just call me,” the drunkard paused dramatically, “Asombra.” Spanish for “shadow.” This was going to be a good one, I could tell…

“Asombra” chattered on and on with Tony while largely ignoring me, something I was grateful for since I was enjoying my solitary sandwich. Still, I overheard tidbits of mad conversation from the old man as I chewed my bread. Apparently, along with having a strange name like Asombra, he was also a painter. A stay-at-home painter. And everybody in Perico knew who he was.

“Now, you can ask a’ybody here in this town,” he blubbered, “ask them who Asombra is. And THEY ALL KNOW!” He paused to gulp down more wine. “You ask them and they’ll tell you, ‘ASOMBRA?! THAT ASOMBRA IS UN HIJO DE MIL PUTAS!!” Then he laughed and laughed and laughed, ending his story with a bellowed “BASURA!!” while pointing to himself.

Asombra continued in similar fashion for some time, and I caught more tidbits of his loony drunk life while Tony was forced to listen on. The phrase “I fucked my stepmother, and I’ll never cheat on my stepdaughter….BASURA!!! Hahahahaha…” was probably the most hilarious thing I heard the old painter bellow into Tony’s face.

While Tony was carrying on with Asombra (at least the old man was sharing his wine with us), I struck up a conversation with the guy next to me. He was Marco, a tobacco picker from San Antonio de los Cobres, the small town I had passed more than a year before when I crossed into Argentina vía Paso Sico. We got along quite well, and he seemed to be a relaxed and fun guy. I asked him about temporary work opportunities for tobacco pickers, which were unfortunately rather limited for a foreigner who only wants to work for a few weeks.

After a few hours Tony went off to Asombra’s house (apparently the old man had invited him over for the evening, and my Padawan wanted to capitalize on the opportunity to have a couple of nice mattresses for the two of us – even if they were in the house of a crazy, incestuous drunkard). I kept talking with my new friend Marco from San Antonio de los Cobres, drank his beer, and smoked about a pack of cigarettes.

Tony came back around thirty minutes later, triumphantly holding up a shiny key for me to see.

“Good work, Anakin!” I said. “Now, come and drink some more beer with my friend Marco!”

And so we did. We drank, and drank and drank, and while we drank I smoked an additional pack of cigarettes (good thing they’re so cheap in Argentina) and chewed almost an entire bag of coca leaves. Towards the end of the evening a fat, jolly fellow (also dipping coca, as per to the status quo of Northern Argentina), joined our conversation.

“You play music!” he shouted, seeing Tony’s violin. “You’re musicians!”

“Yes, we are,” said Tony. “We play music for change on the street.”

The fat man dug around in his pocket for a moment, then came out with a shiny fifty-cent coin. He slammed it down on the table with a metallic clink.

“Here is my money! I want to hear music!” bellowed the fat man good naturedly. I grinned, pocked the fifty-cent piece, got out my harmonica, and began playing random blues riffs. The fat man was hugely amused by the whole thing, and gave another fifty-cents to Tony as he played classical music on his violin.

“Beautiful!” declared the fat man once we had finished. “Just beautiful!” He shoved another wad of coca into his mouth and then asked, “If you two crazy musicians would like to stay at my mother’s house tonight, you’ll be more than welcome!”

Thanks for the offer,” I said, “but I think Tony has found a place for us with that crazy painter Asombra.” I looked at Tony for additional confirmation, who nodded and held up the key.

The fat man waved the key aside. “No problem then! But if you change your mind and want to stay with me, just say the word!”

We continued drinking, and found ourselves quite drunk by about eleven. Around that time Asombra returned with an old, ugly woman in tow (perhaps his stepmother), and declared he needed the key back to his house. Since we had another place to stay by then, Tony gave the key back without hesitation – it looked like we would be sleeping in the fat man’s house after all.

Around midnight the place closed; Marco, myself, Tony, and the fat man needed to go and find another place to drink. “To my house!” declared the fat man, and to his house we went. However, as we were preparing to leave, Tony ran point-blank into a low-hanging tin roof and tore an impressive gash into his hairline.

“Stupid low roofs,” he muttered as I and my new friends cleaned the blood off his face and powdered cayenne pepper onto the wound. This is apparently an old Latin American healing technique. I’ve seen it used several times in the past, and it seems to work well.

“There, good as new!” declared the fat man as he sprinkled the last of the pepper on the cut. “You’ll be fine in no time!”

And he was. On the walk to the fat man’s house Tony seemed perfectly coherant; the two of us waited outside the local liquor store while Marco and the fat man bought more beer. Unfortunately, normal beer sales were not permitted in Argentina at 0030 on a Sunday night, so the beer was sold to them in big plastic water bottles and well out of sight of the local authorities.

We came to the fat man’s house, which was near the place we had been drinking earlier. The four of us sat in the yard and worked at finishing the rest of our booze before passing out on our first mattress in about a week.

For some reason or another, we decided to go inside to drink for a little while, and I carelessly left my cell phone, hand sanitizer, and small pocket radio on the ground out in the yard. About twenty minutes later, I realized my mistake and excused myself to go and look for the items I had left behind.

However, when I got to the spot I had left them, I found them to have mysteriously vanished over the course of twenty minutes. No matter how hard I looked I could not find my cell phone or radio there in the grass. I went back inside and asked if anybody had seen them.

“No, but I’ll help you look!” said Marco, who came outside with me. After only ten seconds of searching in places I had already looked, Marco suddenly miraculously found my radio! Good job Marco! Hmmmmm…..

It was obvious he had pocketed it in hopes of me forgetting where I had left it. Then Marco, my supposed friend, would have had a free radio. But at least I got my radio back, and it was all good and well….until my cell phone refused to reappear. I knew Marco still had it, or had hidden it away somewhere. Here’s how:

Apart from the obvious radio-plant, Marco had been alone in the yard while I went inside with the fat man and Tony to make sure his head injury was doing okay. Marco probably spent a good fifteen minutes out there alone. Secondly, he had cheerfully returned my hand sanitizer while we had been in the house, another item I had left right next to the phone and radio.

I went back inside and declared my cell phone lost. The fat man began to get very distraught, telling me “No-one loses anything in my house! It’s impossible!” He figured my phone must be out there somewhere in the yard, and so all three of us, with Marco bringing up the rear, went to search the entire yard for my phone.

It of course never resurfaced. All three of us figured out pretty quickly that Marco had stolen my phone and was now refusing to admit it, even though it was obvious it was he who had stolen it. I felt very disappointed; Marco had seemed like such a nice fellow.

The night ended with the fat man angrily kicking Marco out of the house (presumably leaving him with a couple of black eyes) and coming back in and apologizing profusely for what had happened (“…impossible to lose things in my house…”). He even offered to give us money, but I told him that the simple act of giving us booze and a soft bed to sleep was more than enough.

The next morning we awoke around eleven – the first time since we’d left Santiago that we had slept later than eight-thirty. The fat man (we never got his name) sent us to the local supermarket with fifteen pesos to buy some bread, ham and cheese. As we ate our hangover away, the fat man told me that there were many strawberry farms in and around Perico.

“Right now is actually the picking season,” he said. “You two could probably find work there if you tried. They pay fifty pesos a day.”

That sounded like some pretty easy, much needed money for myself and my Padawan learner, so we decided that we would seek out the strawberry farms later that afternoon. After we finished out lunch the fat man left for Jujuy and pointed us in the direction of the strawberry fields of Perico. He wished us luck, gave us the remaining ham and cheese, and waddled away around the corner.

As usual for the north of Argentina, it was a sweltering afternoon. We walked the few kilometres back to the highway and began searching for the mythical strawberry fields, where we would earn fifty pesos a day and go to sleep with bellies full of fruit. The fat man had given us no specific directions, and only said that the fields were around the interstate. I went to a small farm nearby and asked the old man sleeping in the grass next to the house where we could find the big fields.

“La Pampita is what you’re looking for,” said the farmer as he lazed in the afternoon sun. “I’ve only got a few strawberries myself, nothing that my son can’t handle. La Pampita has huge fields, they’re always looking for workers.

“Can you tell me where to find La Pampita?” I asked.

He pointed south. “You’ll find it about two kilometres up the highway headed towards Salta.”

I thanked the farmer and left with Tony in the presumed direction of La Pampita. There were many farmy-looking places on the road to Salta, and it wasn’t clear to us exactly which one was the place we were looking for. In order to not accidently pass it up, we went to every farm we passed and asked for La Pampita, which was always just a little ways further down the road. We attracted some stares as well, and some of the farmers couldn’t understand our accented Spanish.

Finally, after hours of searching, Tony and I managed to locate the fabled La Pampita. The fields were indeed huge, and we could see bent over figures in the distance picking small red fruits from the plants on the ground. We asked around at every farm in La Pampita, but everyone seemed to be with plenty of help for the season. Around five-thirty, we gave up.

“No strawberries for us, I guess,” I said, sitting in the dirt alongside a field.

“They look so delicious…” said Tony, who was practically salivating. “I want to steal a couple.”

I looked around. There were no farmers in sight. “Go get some, then.” I said. “I’ll watch our stuff.”

Tony looked furtively around him and darted suddenly over into the field, coming back ten minutes later with a handful of ruby-red strawberries.

“You dirty little thief,” I said, grinning. “How many did you get?”

“Enough,” said Tony, pouring out at least ten more big strawberries from his pocket. We collectively inhaled at the sight of such riches, rubbed our hands together, and said in unison, “Let’s eat!”

———————————————————————————————

Since it was late by the time we had finished our hunt for strawberry work, we decided to spend one more night in Perico and try for Formosa the next day. We walked to the other side of the highway and made camp near the Jujuy international airport. As I lay in my hammock between two old trees alongside a small stream, I dipped coca and listened to Argentine folk music on my recovered pocket radio, falling asleep to the sounds of accordions, fiddles, and Tony scribbling something into his notebook in Chinese.

The next morning it was off to Formosa. After a surprisingly short wait, a small car somehow managed to pack both us and our packs into the back seat and drove us about thirty kilometres down the Ruta 34 to San Pedro de Jujuy. From there, we simply waited.

Tony made a short trip to a nearby house to get some more water, and we melted in the unforgiving heat. Finally we decided to change spots and walk further up the road, as a local had advised us that a better spot lay about a twenty minute walk further up. On the way I stopped to spend my last seventy-five cents on one piece of bread and a cigarette. When we got to the new spot it did seem marginally better; the important thing was that it seemed the most trafficked exit out of San Pedro de Jujuy and further down the 34.

As we waited, a man passed by on a small ATV. To our surprise, he came back about five minutes later and gave us about three joints worth of Paraguayan weed. His explanation was, “I’ve got lots, and you guys look cool.” Thanks, random guy on the ATV in San Pedro de Jujuy!

Soon after getting our free grass, a very unlikely vehicle pulled over for us: an ambulance! I found this rather ironic since I had just been given weed, and now I was about to ride in an ambulance. This would be my second ride in an ambulance (the first being for about 30 kilometres in southwestern Peru), and these drivers took us much further than thirty kilometres. After nearly two hours we arrived to the town of Pichanal, a mere fifteen or twenty kilometres from the start of the Ruta 81, our road to Formosa! I gave the ambulance driver a Cuban coin I had that I had traded a Taiwanese coin to T for. Cuban doctors are the best; what better gift for an ambulance driver?

In Pichanel Tony and I went into the local gas station and attempted to buy bread with Chilean pesos. It didn’t work, but the lady behind the counter gave us the bread for free. We were in a rather frustrating situation when it came to money. We had some, it just happened to be from the wrong country! We had planned to change it over in Jujuy (thinking it would be a better price than if you changed it at the border), but as you know we never actually entered Jujuy and went straight to Perico. Of course, small farming towns in northern Argentina are not equipped with places to change Chilean pesos to Argentine pesos (though all local banks accept the Almighty Dollar), so we found ourselves without any Argentine pesos to speak of. Therefore, we were forced to offer to work for food, which didn’t work but did net us a couple of free coffees.

After getting a little bread and coffee into our stomachs my Padawan learner and I went to the outskirts of Pichanel and tried to hitch our way to Embarcación and the start of the Ruta 81. Regrettably, it seemed that our luck for the day would only run as far as Pichanel. The afternoon brought four solid hours of waiting directly under the hot sun with no shade. Obviously, we had quite a bit of time on our hands, and we got to thinking; the best truck to hitch onto would be a Paraguayan one for sure. They would take us directly to Formosa. But how to attract special attention from the Paraguayan truckers?

The next Paraguayan vehicle that passed saw two obvious non-Paraguayans jumping about in the dust with a cardboard sign saying “VIVA PARAGUAY!” with a badly drawn Republic of Paraguay etched into the corner. It did get a lot of sympathetic honks and slow-downs, but at the end no-one stopped for us. Defeated, we retreated back to the service station for rest and more purchase attempts with Chilean pesos.

The lady behind the counter had not changed her mind. No Chilean pesos, though she did like to look at all the zeros on the bills and pretend that $5,000 CLP was actually $5,000 AR, and she was rich! Finally I got the idea to ask one of the Paraguayan truckers waiting for gas and headed to Chile if he could change a little bit of our Chilean money into Argentine pesos.

The Paraguyan looked suspiciously at the plastic Chilean bills I handed him. He had a “Don’t mess with Texas” sticker on the inside of his big rig. I took this opportunity to point out that I was from Texas.

“You’re from Texas, huh?” he said, still examining the Chilean bills. “So tell me, how many Argentine pesos am I supposed to give you for these $3,000 pesos chilenos?”

“Nine pesos argentinos for each 1,000 pesos chilenos,” I said, thinking, “so about $27 pesos.”

“Hmmm….” The Paraguyan looked at me, then said, “You’re not trying to fuck me, are you?”

“Of course not. That’s the exchange rate.”

A friend of the trucker came up, saying “What’s up, what’s going on?”

“This Texan is trying to fuck me, I think,” said the Paraguayan, opening his wallet. “But I’m going to do it anyways.” He handed me the $27 AR. “This better buy me lunch in Chile!” he said, waving the plastic Chilean pesos in my face.

“It will, I assured him. “Thanks!”

“This Texan’s trying to fuck me…” I heard him muttering good-naturedly as I left.

And so I returned, triumphantly clutching twenty-sevenArgentine pesos in my hand. I slammed it on the table where Tony waited.

“We’ve got pesos argentinos,” I said. “What should we buy?”

We both agreed on “cigarettes and bread,” and puffed and munched on the two as we tried to figure out what to do next. I left Tony for about an hour to go and find a place to camp before it got dark, and settled on a few trees out in the back of a field about a twenty minute walk from the gas station. I hung my hammock, rolled a joint of the Paraguyan stuff, and puffed it peacefully while swinging carelessly back and forth in the cool night air. Tony talked and talked and told me more crazy Chinese stories, like the one about a boy who was born at the age of three and wrapped in a meatball, who later went on to kill a dragon at the age of six and commit suicide at the age of seven by skinning himself and cutting himself into tiny little pieces.

Seriously, the Chinese have some of the most random, trippy stories I have ever heard in my life. Who gets born in a meatball at the age of three? What sky-high Chinese story-teller came up with that one? And to top it all, the Meatball Child is now a God. It must have been really confusing to live in ancient China…

Needless to say, it was the perfect material to go with the potent Paraguayan grass; I fell asleep on the ground (having let Tony use the hammock for the night), snoring, giggling about meatballs, and swatting the occasional mosquito.

The next morning we had the burning desire to get out of Piranel, the town that had made us wait five hours the day before in merciless boiling sunlight. We awoke as early as we dared and headed to the same spot from the day before, hoping that it would have more friendly people passing by in the morning.

We played “Stones” for about fifteen minutes before a pickup stopped and drove us fifteen kilometres further up, dropping us off at a different YPF service station. Here we noticed an excess of stopped Paraguayan trucks, and decided that it couldn’t hurt to ask them all to take us to at least the Ruta 81 just five or six kilometres ahead. One driver agreed, though he was at the time having some problems with his truck. He told us to wait for him nearby and he would pick us up on his way out.

About twenty minutes later the problem seemed resolved, and the truck began heading for the exit. However, it stopped again before getting there, and spent another half hour idling next to another Paraguayan truck as they fiddled around with more hoses and cables. Finally, the truck crossed the street to where we waited at a tire shop…and dropped off a tire for patching.

“Are you still going to take us?” asked Tony.

“Sure, no problem.,” said the driver, cleaning oil off his hands with a red cloth. “Just as soon as we get this tire fixed.” He pointed to an old Japanese mini SUV on his trailer (almost all the Paraguayan trucks in northern Argentina are carrying old Asian cars), and said, “You guys can ride in there!”

“In the car on the trailer?” I asked. “Really?”

“Sure!” said the trucker, before leaving and fiddling with the spare tire once more.

Awesome. I had always wanted to ride on one of the old cars on a car trailer. Our mini-Nissan was the first car on the second level of the trailer. Tony and I stashed our packs in the back and hopped into the front seats just as the big rig started to move.

“Vrrroooom,” I said childishly as we took off. “Look man, I’m driving the semi,” I said, mock steering us around the corner. I really was excited; this was sure to be an interesting ride! Alas, the trip was not due to start yet. The truck simply drove to the other side of the road and parked while there was more work done on the tires. Finally, after another hour of waiting in the little Nissan, the work was apparently finished. Just as I thought we were about to take off, the driver shut off the engine and went to eat lunch.

A full two hours after we had gotten into the Nissan, the motor of the big rig rumbled and we were finally off!

The Nissan didn’t have any battery left, though the keys, complete with keychain with Japanese characters on it, were in the ignition. The only bad thing was that we were not able to roll down the windows, since the Nissan did not have manual window handles. So we improvised, shoving a couple of old shoes that were laying around into the door space and let the wind of the highway cool us down.

When we arrived to the 81, the driver stopped and asked us where exactly we were going. Formosa! we said excitedly and repeatedly. The trucker agreed to take us as far as a town called Juaréz, which lay an unknown number of kilometres to the east. As the truck rolled off towards Juaréz, Tony and I relaxed and enjoyed the ride. Juaréz could be ten kilometres further down, or five hundred kilometres further down. We could only hope it was the latter…

Now, we knew that it was illegal to be riding in this spot of the truck, so we made a point to duck our heads down every time we passed a police checkpoint. However, after about two hours of driving, a random checkpoint appeared out of nowhere and the police stopped the truck for a good five minutes.

We were, of course, discovered. The police told us that it was illegal to ride in a car that a truck is pulling, and to put our shirts back on and get out of the car. We complied, and after a short search the Paraguayans rolled off without us, leaving us very much in the middle of nowhere.

“You two must take the bus that is coming,” said one of the policemen. “And no hitchhiking!”

I was at a loss. No hitchhiking? That was literally the first time I’d heard that from a policeman after two years of hitchhiking around Latin America. I had assumed that was something only American cops would say, but I suppose I assumed wrong. Tony and I didn’t have enough Argentine pesos left for the bus, so we just started walking down the highway. The cops didn’t stop us.

Tony was in a foul mood, not only because we had been kicked out of our sweet ride to Juaréz, but because he had forgotten his cell phone on the dashboard of the old Nissan.

“Fucking cops, stressing me out so I forget stuff,” he muttered. “The Gendarmería de Argentina sucks, man!”

That it did. We walked in silence for twenty or so minutes, then took a rest after we had gone about two kilometres.

“Man, I’m so mad I could walk to the next town,” said Tony. “That was a perfect phone! Good video and audio quality, and it took beautiful photos! Now all my photos since San Pedro are gone!”

I patted him on the back consolingly. “Yeah man, it sucks. I’ve forgotten stuff too, it’s really frustrating.”

“Fucking cops,” he said again.

————————————————————————————————-

As the sun began to go down over the empty countryside of the providence of Formosa, Argentina, we began to run out of water. Fortunately, we managed to refill the two bottles we had from a passing truck, though he still refused to take us to the next town (even though it was close to fifteen kilometres away). Soon the bus we were supposed to take passed. I flagged it down and asked again how far it was to the next town. “Close to twenty,” said the driver. I hesitated for a moment, wanting to try and cut a deal with him, but the driver didn’t even give me a chance to think and drove away without letting me say anything.

First, the cops kick us out of our sweet little non-functioning Nissan and tell us no hitchhiking. Then, a truck we stopped for water won’t take us fifteen kilometres to the next town. Then, the bus doesn’t even give you a chance to negotiate. Formosa was not turning out to be a very welcoming place for us.

After awhile the sun was almost down over the strange vegetation of the Ruta 81, which consisted of small, short trees and tall subtropical cactuses. As it got darker and darker Tony and I swatted the thousands of marijiís (remember them? Guyaramerín) and simply kept walking.

“We’re going to walk clear to the next town,” said Tony. “We’re going to do it.”

“Then let’s go man!”

We walked, and walked and walked. After about two hours of walking we stopped for a break and I rolled another one of the Paraguayan joints, which we smoked while laying in the middle of the dark, deserted highway and staring happily at the stars. Then it was more walking – walking for hours and hours, or possibly days or weeks. All I knew is that I reached a point where I didn’t realize I was walking or even carrying a pack, and I just drifted along that dark road for a millennia or more, my mind wandering further than my body ever had.

Tony didn’t seem to be doing so well; his breathing was getting heavy and labored behind me as he sucked the warm air in huge gasps.

“We’re almost out of water again,” he pointed out breathlessly after about ten kilometres.

I looked. So we were. Luckily, I had spotted a campfire burning some hundred metres ahead. “Campfire means people, and people mean fresh water,” I told my winded Padawan. “Let’s go and ask for water.”

We approached the campfire, which turned out to be burning in the back porch of a small wooden house.

“Hello?” we shouted at the house. There was a slight movement, and then we saw a flashlight pointing at us. Before I could get another word out, two dogs materialized out of nowhere and began enthusiastically barking their stupid heads off. They were extremely loud and nonstop, making it impossible for the people in the house to hear what we were saying or vice versa. I caught a couple of words through the sonic barks that sounded like they came from an old man. They sounded something like sale, sale, sale de aquí! Get, get, get out of here!

Now this is usually the language that people in Latin America use for dogs, so I assumed the old man was talking to his hounds so that they would shut the hell up so we could hear one another. Then I saw the moonlight glint off something long, black and shiney…

Suddenly there was a loud POP, and I heard something whizz over my shoulder at approximately the speed of sound. It took me a moment to register what had happened, but then I realized it – the old man had shot at me! I had just almost been shot!

I’ve fired a lot of guns in my lifetime, mostly back home in Texas, so the sound of gunfire is not a strange one to me. However, it’s a little different when you’re on the receiving end – that whizz of the bullet zooming over your shoulder, how you can feel the projectile rustle your hair as it zooms right by your brain…well, it’s quite another thing altogether.

Needless to say, Tony and I promptly decided to look for water in other places, and hurried back over to the road.

“We were shot at,” I said, still in a daze and especially disturbed since I was still a little bit high. “That guy almost killed us.”

“And we’re still out of water,” said Tony sadly.

The adrenaline was pumping through our veins pretty hard after this, so we had the energy to walk for a good two or three kilometres more. After awhile we noticed in the distance ahead of us the lights of an approaching truck. As we walked they got closer and closer until the truck was just about to pass us by. Suddenly just as it was almost on top of us, the truck swerved violently to the right and began plowing over the shoulder of the road – right to where we were walking! Tony and I threw ourselves as far as we could into the bushes along the side of the road, just barely avoiding death for the second time in less than half an hour! What was with this road?! The Ruta 81 was out to get us both! This entire country wanted us dead!

As we passed by the spot where the truck had swerved, we realized that the swerve had been because of a large pothole in the road, which we assumed the trucker had not been prepared for. Hence, he over-corrected to his left, drove on the opposite shoulder, and nearly killed us both. And he didn’t even stop to apologize, the bastard…

“I think we should stop,” said Tony. “I seriously can’t walk anymore…”

I still had plenty of energy, but I figured the road had given us enough signs already. I found us a spot to camp right alongside the highway, cleared out a couple of thorny bushes (every bush in this part of Argentina seemed to be populated by extremely thorny bushes), and we slept right there on the ground until early the next morning.

When the sun came up we were still out of water, so Tony went out to the road and tried to stop a truck for some more while I finished packing up camp. The first big rig that passed stopped, and though he didn’t have any water he did offer to take us as far as Las Lomitas.

We drove in relative silence to Las Lomitas. Tony and I told the driver about our near-death experiences from the night before. His jaded response was that most of the people in this part of Argentina were 100% native people – people who lived their lives hand in hand with superstition and an extreme, burning distrust for outsiders. As we drove by I saw a couple of kids – young boys maybe around eight or nine – starting random fires on the side of the road and jumping (dancing?) around them.

All of a sudden I felt extremely unwelcome in this part of the world; this savage Ruta 81 – hell, this entire region wanted us out. Landscapes that had looked beautiful the day before from the dead Nissan now looked hostile and threatening. The morning sky, while it was in reality grey, looked green and menacing. We rode in silence down the Ruta 81 – the wild, extreme north of Argentina – surrounded by superstitious, murderous farmers and wild children dancing around bonfires. The Ruta 81 was no normal route – it was fraught with sour-faced Gendarmería who kick us out of the best ride we’d gotten since getting into this damned country, merciless sun and boiling asphalt, tons of metal barraging down the shoulder of the road and nearly decapitating you, bullets whizzing by your neck so close you can hear the spiff-crack as it breaks the sound barrier right next to your ear. No, the Ruta 81 was definitely no normal route – it was the devil’s route.

And we had no business hitchhiking with the devil…

—————————————————————————————————–

This gloomy attitude persisted until we arrived to Las Lomitas. Here we met Maxi, the man who changed the entire day and outlook on the area. He came as a much needed friend when we felt completely unwanted by everyone there.

Maxi worked at the local YPF service station, and greeted us with a smile and two coffees. He was interested and happy to see us, despite the fact we didn’t buy anything. He let us shower, change clothes, and bought us a pack of cigarettes. And he let me write this post.

Maxi saved the day.

Viva Maxi! Viva Las Lomitas! And let’s hope we get off the Ruta 81 soon, because I still don’t entirely trust this bastard…

The Modern Nomad

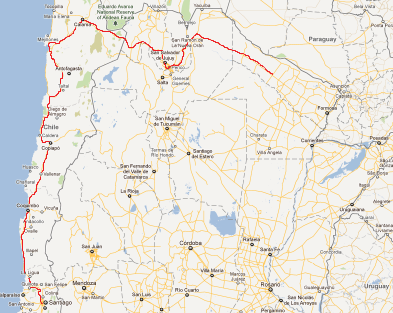

Reference Map

awesome stories! ill be in argentina in a few months with my wife and were working on a farm in cordoba and we were hoping to hitchhike around the area, hopefully no one shoots at us!

Nah, you’ll be fine! Just try not to venture around in the dark looking for water :P Buena suerte!

-MN

Just finished reading both your last posts. It took me some time to read them, so it must have taken a really long time to write them! Thanks for taking the time to do them. It makes me feel like you are still a daily part of my life even though you’re far away. Of course, you are always a daily part of my thoughts.

Dad and I are reading these together this morning and laughing at your funny comments. Well written, son. Hope you and Tony have better luck in your future adventures.

Love,

Mom

You know I take high priority in the writing of my posts, especially for the benifit of you and Dad :)

Can’t wait to see yall in December, wherever it is! We should Skype sometime……

Love

Patrick

A fellow hitchhiker directed me to your site a few weeks ago and I started reading some of your last posts and I was hooked! You’re a great storyteller.

Start thinking about that date, because our roads may cross sooner than we anticipate ;) I’m heading to Central America and working my way down. So happy thumbing and see you on the road :)

Right on! See you in the jungle….:)

The force is strong with you. This post was really a change of pace, looking foward to the next one.

Still waiting for your PCT tale, Skywalker. What gives? :P

-MN