This is the first part of T and I’s 1 month hitchhiking adventure in the north of Chile. “Chapter” format inspired by fellow hitchhiker Chale Gram’s post entitled “The Lima Chapters.”

Written from Santiago de Chile

The Atacama Chapters

Chapter One

Santiago Blues

The screech of the metro train brakes (yellow line, last stop to the north) howled their way around the Vespucio Norte subway station as the doors opened and the driver called out last stop. The few remaining passengers, myself and T included, mulled their way off the train and up the stairs leading off the platform and onto the street above.

The morning air was a little better than usual in Santiago, (it had rained the day before and everybody knows that Santiago is only beautiful after the rain), so the exit up the yellow-lined stairs up into the daily chaos that was the Chilean capital was not as toxic as I had become accustomed to. Vespucio Norte, last stop for the largest underground subway system in South America, is situated (rather conveniently for hitchhikers) right on the northern sector of the Autopista Central – which is just a fancy name for the Ruta 5, Chile’s main transportation artery which would take us (with luck), relatively quickly to the country’s barren northern lands.

This would be the first time for T and about the fourth time for me hitchhiking desert-bound from Santiago, and the difference from our peaceful little thumbing adventures in Magallanes and this screaming, clashing highway pouring out of Santiago like a polluted river overflooded after a solid week of acid rain was more than noticeable. In Magallanes we would wait for hours and walk dreamily down small dirt roads, counting guanacos and figuring out their ratio to sheep. Here, after short blackride on a scraggly north-bound metro bus covered with unintelligible graffiti, we arrived to a glass-covered shoulder next to a trash-littered entry ramp which read “Los Vilos, 210,” (though the local hoodlums had disfigured it with spray paint, causing it to read “LAs PUTAAAS, 210.”) We set down our packs and began the long, not entirely enjoyable process of thumbing our way out of a Latin American metropolis.

“Maybe I should put my hair down,” said T after half an hour of semis and autos alike whooshing by without a second glance.

“That, and you stand in front of me,” I replied. “I would rather them see your face before mine.”

Systematically, T and I changed places while she put down her hair and fluffed it up; we grinned hopefully at a huge Freightliner rumbling onto the freeway, whose driver grinned back at T and, upon noticing me, pretended to be fascinated with something on the other side of the road, staring intently at a blown out tire until he passed us and it was safe to look right once more.

“He wanted to stop for us,” commented T as she adjusted her scarf to a more feminine position.

“He wanted to stop for you,” I corrected her with a smile. “Then he saw my ugly face and changed his mind.”

T laughed lightly. “Maybe you should grow your hair longer and start stuffing a bra.”

I snorted. “Are you kidding? And get their hopes up like that?” I gave an expression of exaggerated fear. “They might not be so friendly once they find out that my “sensual breasts” are made of wadded up napkins and toiled paper.”

“True. Better let me do all the work.” T flung her hair over one shoulder and gave her sweetest smile to a passing Toyota, whose driver grinned goofily back and nearly plowed into the concrete divider.

The sun rose slowly over the grey city as the morning progressed slowly onward. My arm was in its automatic “outstretched thumb” position, while my body basically ran on autopilot; I leaned forward and instinctively grabbed my hat in anticipation of the inevitable blast of wind following the fast moving semi-trucks as they roared by less than a meter away. I waved languidly back at a few passing trash bums who grinned at us as they picked through the rubbish in the ditch, in search of cans and bottles to cash in at the recycling centre for petty change.

“Man, this is taking forever,” said T after yet another hopeful semi passed us over and rumbled north without us. I looked at my clock; it was ten-thirty.

“Are you kidding?” I scoffed. “It’s only been two hours! Santiago isn’t so easy to hitch out of, you know.”

“Well I hitched south out of it before, and I only waited twenty minutes.”

“Well, that was when you were alone.” I put my arm around her and gave her a kiss on the cheek. “Welcome to hitchhiking with a man! Trust me – two hours is nothing.”

T rolled her eyes. “What was the longest you ever waited, then?”

I thought for a second. “Three days.”

“Three days?”

“Three days,” I confirmed, nodding. “Tucumán, Argentina. What about you?”

T shrugged. “Maybe 45 minutes, I guess.”

“Oooooo,” I said, laughing. “Well, you’re gonna shatter that record in the next month or two, I promise you.”

T grumbled and lit a cigarette. “Why don’t you make a sign?” she said suddenly. “We could use a sign.”

“All right,” I agreed, taking my marker out of my pocket. “I’ll go and look for some paper – you keep hitchhiking.”

T waved me off and beamed hopefully at a Volvo semi truck loaded with cabbage, who honked several times before noticing me and accelerating northward at an alarming rate. I trudged down into the rubbish-filled ditch, whistling a tune and digging around for a suitable piece of cardboard to transform into a sign.

Suddenly I heard the whooshing of air brakes and looked up to see T sprinting up to a slowing green semi. She tugged open the door, chattered something to the driver, then looked back and waved frantically for me to come over. I climbed out of the ditch and grabbed both our packs, hunching monster-like to the idling truck ahead. When I got there T was already sitting in the passenger seat. The driver looked over at me with a confused expression.

“Who is he?” the trucker asked T, eyebrows raised.

“Oh, he’s with me,” she said lightly, taking the packs I passed up to her. The trucker suddenly looked doubtful.

“Weren’t you digging around the trash in the ditch?” he asked me incredulously.

“I was looking for some cardboard,” I said by way of explanation as I hopped into the passenger seat next to T. “To make a sign,” I elaborated when he still looked perplexed.

“Oh…” he breathed out, slowly putting the truck into gear. Then he gave a small laugh. “Honestly, I thought you were a homeless person looking for bottles.”

“Not this time,” I smiled back.

The big semi slowly chewed up the black asphalt ahead of us as we plodded north. Santiago faded stubbornly into the distance behind us, the smog and trashy on-ramps vanishing piece by piece into the grey afternoon light as the desert drew closer and we slipped into the rocky pre-Andean hills of central Chile.

Chapter Two

Oh, the Philosophy of it all….

T and I hadn’t much time to spend together since having met up the night before with her friend Perla at an expensive Peruvian restaurant (I ordered tap-water, causing the waiter to give me a staunch, holier-than-thou look and not return my smile for the rest of the night), so we spent our time hitchhiking out of Santiago simply catching up. The month we spent apart had been hard on the both of us, and it didn’t help that the previous night had been spent by me on Perla’s shag-carpet (really delightful thing, actually – soft enough to provide a little cushion and firm enough not to cause my back to hurt in the morning), and T sleeping in the room adjacent with her friend. After a whole month apart, we wanted to sleep together.

Therefore, due to our state of togetherness, my average wait out of Santiago and T’s longer than usual one went by pretty quickly as we laughed and bickered good-naturedly over hitchhiking techniques and little minuscule details like how high to hold your thumb and how you stand on the shoulder.

Then the trucker came and suddenly we sat in relative comfort in the interior of what was basically the mobile home of our driver. I maneuvered myself to the left and sat on the bunk plastered with Spiderman sheets while T occupied the passenger seat. As we rode north (destination still unknown, just vaguely north and then mentioning something about a desert), the trucker (a young fellow who seemed like a nice enough guy after all), chatted with T about things that were happening in his life while I simply sat back and relished the fact that I had only waited for two hours and I was already on my way north from Santiago.

There I sat on the cushioned bed of the semi, bouncing along the merry Ruta 5 and reflecting on a relatively new experience: hitchhiking, for the first time on a long trip, with a friend – and in this case, more than a friend: a lover.

A fellow hitchhiker and friend of mine named Chale Gram once wrote while he hitchhiked with a companion: “Division of my brain hemispheres was obvious. I like to travel with others, but I’ve traveled so many days alone that I’m like an old man stuck in his ways…” I knew what he meant; all those little nuances of travel, nuances that people like me and Chale have sunk into and silently developed alone – every little detail of hitchhiking that can’t really be taught, only learned and then repeated a million times over until it becomes your own personal internal Road Bible, lodged conveniently somewhere in the recesses of your brain – and whenever some other person comes along and breaks one commandment or another by saying something like for example, “Hey, you should always maintain constant conversation with the driver because it is you’re duty, man,” and I’ll say something like, “To hell with that, if he doesn’t want to talk after I initiate conversation then I’ll go back to staring out the window or half-reading some book in Spanish I still don’t fully understand.”

I remember once hitchhiking through northern Argentina with a guy from Buenos Aires I met at a gas station in Tucumán – Alejandro. Some of you older readers may remember him, and yes, that was when my three-day wait took place – but I digress. I travelled with Alejandro for a solid week, all the way from Tucumán to Buenos Aires, and recall noticing all these different techniques and ideas he had for hitchhiking, so different at times from my own. Why did Alejandro want to do this, why did he figure that was the best way to flag down the car or talk to truckers at the gas station, and blah blah blah blah – we fought over lots of things and even had a nasty row once we got to Buenos Aires – and maybe now that I think about it we both had shitty ideas since we were stuck for three days, after all – but the issue I’m driving at is essentially this: why do we travellers, while at times yearning or even desperately wishing for some small break in the solitude that is our lives on the road often clash so forcefully with our fellow warriors of the route? Even when I discuss travelling with other travellers we invariably disagree on several key issues, making me suddenly realize that the traveller is not only his own species – he is divided into thousands, perhaps millions of similar but still subtly different subspecies, not one being classifiable into the same category as the next.

You have a few main categories of course, like for example Travelleri busus hostalus,(bus-riding hostal surfers)Travelleri liftus campamero (hitchhiking campers) Travelleri cyclesti campahostalus (cyclists who alternatively camp and stay in hostals), and so on and so forth. But then you get really down into it and you realize that little differences which at first may seem negligible actually effectively divide the genus Travelleri into an infinite number of distinct subspecies – for example the difference between Travelleri busus hostalus hippera veganauti and Travelleri busus hostalus drinkuri fuckaboutous: you’re typical hippie vegan flower-bandit and a rip-rawling, heavy-drinking sex tourist, whom I’m sure frequently find themselves bunk mates in their hostels and discover that they get along rather un-famously.

The same goes for us hitchhikers, and while you may have to tack thirty or forty different fake Latin names on there you’ll eventually discover that (inevitably) there’s something you don’t exactly see eye to eye on, and sometimes that is just the thing that will end up driving you apart and back into your respective solitudes because, let’s come clean and admit it, that’s all we really wanted in the first place even though we were happy to talk to something other than our packs for a few days. It goes even further to show that a traveller is sometimes so different in the way he looks at the world from say your average 9 to fiver or even some really neat people like astronauts or rescue divers, that we are pretty much in a different genus or maybe even a different phylum with extra mental arms or only three mental fingers. The species mix and some get along and some don’t, but by the unbreakable laws of nature and human tendencies to say fuck you I’ll do what I want, we hitchhiking travellers usually coerce ourselves into our own solitude. After all, we are by nature solitary animals, sometimes pairing off into small groups of two or three but invariably finding ourselves, weeks months or years later, back to the way we started out: alone.

I meditated on this despicable and lovely circle of life as T and the driver chattered on – all at once realizing that for the first time in my life I may have met another traveller similar enough to myself so that we could stand each other’s respective presences for more than a few weeks at a time. Sure, T’s nuances were sometimes different from mine, something inevitable and expected since she of course also had her own internal Road Bible filed away somewhere in the creases of her brain – but despite the things we disagreed on, our agreements usually rang stronger than our quarrels. In any case, it was sure nice to have someone to talk to other than my pack.

With that thought in mind I happily relaxed and enjoyed my ride in the cab of that semi with T and welcomed in a new chapter, or perhaps even a new book, into the volumes of my life. I leaned back and lit a cigarette as the trucker “accidently” zoomed by a weigh station and spent the next half hour talking nervously about the fact that there were too many weigh stations and anyways, 45 tons was a really low maximum load.

Chapter Three

Squat

T and I found ourselves a few days later in a little fishing town in the Atacama region called Bahía Inglesa. A long-haired fellow had picked us up in Copiapó earlier that day and, after reveling to us the joys of eating live clams (still quivering desperately as we slurped them down raw with lemon juice, the poor delicious things), left us with a smile and a wave in this little town about an hour before sundown. T and I, like good campers, utilized what was left of our daylight to scout out a good place to set up the tent.

After giving the town a few good walkovers, we decided on a thin crescent of sand a few kilometres away to set up for the evening, and made the short walk down the beach in front of a brilliant sunset. However, upon reaching the crescent we discovered that the tent stakes had some difficulties sticking into the loose sand.

“I don’t think this is going to work,” said T after the tent once again flopped uselessly onto the dune.

“Hm,” I responded vaguely, scanning the ocean absentmindedly. “We may have to explore other options,” I said, lighting a smoke.

“Like what?”

“Well, we could just sleep under the stars.” I suggested. “It’s not that cold out.”

“Yeah, but there’s a wind. I hate wind.”

“True.”

We sat on the sand in silence as the sunlight drained from the sky and the stars began to peek their silent faces out onto the purple sky.

“What about that place?” said T suddenly, pointing. I turned and looked. Behind us was a sort of fenced off area with picnic tables, crowned by a grand restaurant and small complex of cinder-block buildings.

“You think so?” I said, turning my entire body to face the complex. “It does look pretty quiet, doesn’t it?”

“Yeah. You think we could get into one of those little buildings? The whole place looks pretty empty.”

I shrugged. “Maybe.” I frowned as I examined the place. “What do you think it is, anyways?”

“I have no idea,” conceded T, still studying the complex. “Why don’t you go and check it out?”

“All right,” I agreed. “Stay here – I’ll be back in a few minutes.”

I left T with the packs and walked up to the fence, which was only glorified chicken wire and may as well have not been a barrier at all. After leaping over I walked the fifty or so metres to the restaurant and complex, noting that there were hardly any prints in the sand at all, except for a few dog tracks.

The buildings were dark when I arrived; I walked around the entire restaurant and found all doors and windows to be locked and barricaded. The cinder buildings were the same, with the exception of the largest: it sported only one entrance, a pair of swinging doors which were conveniently not equipped with locks. I pushed cautiously on one of them, found entry to be easy, and went inside to see what sorts of squatting opportunities were available.

It was a bathroom. Or, more accurately, a locker room, with separate sides for the men and the women, showers, at least twenty toilets, and two separate changing rooms. All in all, the perfect squat. But first, I had to make sure that no-one would come across us in the night…

I tried the faucets, which worked perfectly (with the exception of the hot water knobs), and the place looked very clean and new. Perhaps the complex, whatever it was, was simply closed down for the evening. I went outside to investigate further.

In contrast to the inside of the bathroom, the outside looked rather boarded up. Chairs were stacked, beach umbrellas were locked away, and even the benches and tables were stored in a disused corner of one of the cinder block buildings, which seemed to me like a bit excessive if you were going to open up the next day. Then, I came across a sign:

Resort Bahía Inglesa

Sol, Tragos, y Diversión!

Abierto Noviembre a Marzo

Translated, it read, “Bahía Inglesa Resort: Sun, Drinks, and Fun! Open from November to March.”

We were in June. Perfect. I walked back to the fence, hopped over, and went back to T.

“Well?” she said expectantly.

“It’s a resort – a pretty nice one at that,” I reported. “But we’re in luck: looks like they’re closed down for the winter, and they’ve got some really nice bathrooms that are unlocked.”

T beamed. “Awesome! Well, let’s get inside and get some sleep, I’m tired.”

I concurred. We heaved up our packs over the fence and trotted over to the resort bathrooms to set up our squat.

———————————————————————-

Half an hour later we had a nice little bed consisting of our two sleeping bags and assorted jackets and dirty clothes, all set up on the floor of the ladies’ dressing room. After making a few sandwiches with some bread and ham we’d bought in Copiapó, the two of us sat back on the benches and relaxed.

“This is probably the cleanest bathroom I’ve ever seen in Chile,” said T as she chewed. “Must be an expensive resort!” She went over to one of the nearby toilet stalls and exclaimed, “Look, there’s even toilet paper!”

“Really?” I went over and looked; so there was. A big roll, too. “Wow,” I said, then laughed loudly. “We’re squattin’ in style tonight!”

“That we are,” agreed T as she made herself another sandwich.

Later we explored the locker rooms a bit more, and discovered a big bottle of expensive shampoo in one of the showers. “Too bad there’s no hot water,” said T dreamily when she found it. “I could wash my hair!”

After the novelty of our high-class squat had worn off, we brushed our teeth in the sinks and curled up on our hobo bed for the evening. “Well, we sure did good to find this place!” I said, lying down. “If we hadn’t found it –”

Suddenly I stopped. There were lights shining in from the little windows in the top of the bathroom, followed by the unmistakable sound of crunching gravel announcing the arrival of a vehicle to the nearby parking lot.

T’s eyes widened in the dark. “Shit!” she whispered frantically. “Someone’s coming! We’re busted! Shit!” She stood up quickly, but I stopped her.

“Hang on…we might not be busted…not yet. Let’s wait a moment.”

T sat back down, and we listened with bated breath to the sounds of people walking right on the other side of the wall.

“It’s the police!” hissed T. “Someone called the police on us! We’ve got to give ourselves up!”

“No way,” I shook my head. “Quick, lay down and pretend you’re sleeping.” T did so, the sound of movement on the sleeping bags sounding like someone crumpling newspaper through a megaphone. “If they come in,” I continued in a thin whisper, “we’ll say sorry, explain we couldn’t camp on the beach, and are doing nobody any harm here. Just sleeping.”

We lay in tense silence for several seconds as the footsteps continued towards the door of the bathroom. Then they stopped near the restaurant, and a few voices began talking loudly in Spanish. Suddenly one made a dirty joke about Colombian women and they both laughed. Apparently, they weren’t police officers all – at least not professional ones. Then came the sound of jingling keys and a large wooden door, probably the one of the restaurant, scraping across a concrete floor. The voices went inside and then faded as the door shut behind them. T and I relaxed collectively.

“Well, they’re not cops,” I said.

“Maybe they’re the owners,” said T, still whispering. “They had the keys, after all.”

“Yep,” I agreed. “Or maybe the winter caretakers.”

“We should leave,” said T suddenly, sitting up. “They’re going to find us in here, I’m sure they check the bathrooms every night.”

I shook my head. “Why would they do that if no-one uses them?”

“To check for squatters?” she offered

“I don’t think Bahía Inglesa gets many squatters.”

T sighed. “I don’t know. I still think we should leave.”

I pursed my lips, thinking. A few moments passed in silence; T could be paranoid at times, but nonetheless she was oftentimes right.

I bit my lip, then said, thinking out loud, “If we leave, they’ll see us for sure on our way out. No, I reckon our best bet is to wait it out here until morning. We can get up really early before they wake up. If they even stay the night.”

T still wasn’t very convinced, but she changed her mind when the caretakers (or whomever they were) kept on coming in and out of the restaurant but keeping clear of the bathroom entrance.

“OK, we’ll stay here for the night,” she conceded after fifteen minutes or so. “But we’re waking up at 5 tomorrow morning.”

“Fine with me,” I whispered as one of the footsteps passed alarmingly close to the bathroom wall. T and I settled back into our hobo bed and fell slowly asleep to the sounds of the caretakers getting drunk in the restaurant. It looked like they would be staying the night after all…

———————————————————————-

We awoke at 4:50 the next morning, ready to start packing and leave at five. I had just finished rolling up my sleeping bag when I heard the familiar sound of crunching gravel yet again. T and I froze in our respective packing tasks as we heard a pickup door slam and the same two voices of the caretakers. Somehow, they had slipped away in the night and made it back before five a.m.!

“What the hell are they doing up so early?” I murmured. T had a frozen expression of being caught red-handed on her face.

“What are we going to do?” she whispered frantically. “They’ll know we’ve been in here all night long!”

I sat back down on the bench. “I don’t know. I guess we wait.”

So we did. After ten minutes or so we began to hear a strange, repeating crack-scrape-plop sort of noise. I tiptoed to one of the high windows and peeked out. What I saw were two shirtless men sitting on upside-down five-gallon buckets around a wheelbarrow full of fresh clams. The crack-scrape-plop sound was them opening the clams, scraping out the meat, then plopping it into a nearby pan. I looked at the wheelbarrow again; there were a lot of clams in there.

“I think we might have to wait for awhile,” I told T when I came back from the window.

“I’m not waiting in here all day,” said T reasonably.

“Me neither,” I said. “How about this: we sleep a little more, and if the coast isn’t clear after 10 o’clock, we’ll just have to come clean and tell these guys we were sleeping in their bathroom all night.”

T agreed. “See you at nine…” she said as we drifted back to sleep amongst the crack-scrape-plop of the de-clammers.

We awoke once more a few hours later; another espionage trip to the window revealed the clams to be completely de-shelled and the two men mulling about doing something inside the restaurant.

“This is our chance!” said T excitedly. “Hurry, let’s pack up our stuff and make a run for it!”

We shoved all our gear hastily into our packs and tiptoed to the swinging doors at the entrance of the bathrooms. I poked my head out cautiously, found the way to the exit to be free of de-clamming caretakers, and said to T, “OK, let’s go!”

We slipped out into the morning sunlight with all the stealth we could manage, and once we got to the other side of the bathrooms sprinted for the open gate at the exit of the resort. We arrived ten seconds later to the asphalt of the highway, exhilarated and out of breath.

“Can you believe we got away with that?” laughed T with the too-loud voice somebody uses when they’ve been whispering for a long time.

I cackled deliriously. “No! I thought for sure we were toast when I saw all those clams!”

T kissed me as we held out our thumb for a passing pickup coming from the town, then winked and said, “Now we can tell everybody that we stayed at a five-star resort in Bahía Inglesa…and didn’t pay a dime!”

And it would be the truth.

It really was a very nice bathroom…

Chapter 4

El Ermitaño

For some time, I’ve heard tales from truckers of a strange old hermit who lives smack-dab in the middle of the Atacama Desert alongside the Ruta 5 a few hundred kilometres before Antofagasta. I’ve even seen him and his odd little white house made out of God-knows-what a few times as I passed by, waving at passing traffic with a big empty bottle of water, a huge beard, and suspicious-looking dark sunglasses.

Chilean truckers know him well, and that they should; El Ermitaño del Atacama (The Hermit of the Atacama) has been squatting alone in his little spot alongside the highway near a huge, unexplainable pile of blown-out tires and junk for the better part of fifteen years. He survives by collecting water and food from passing traffic, and is reputed to be one of the strangest people ever to speak to a trucker (which is really saying something). To tell the truth , El Ermitaño is somewhat of a myth amongst the working travellers of Chile – there are many, many different versions of who he is and why for some reason, he one day decided to live alone in the desert in a strange little white house alongside the highway.

“He was a doctor,” affirmed one trucker last year as we passed the hermit hacking mysteriously away at an old piece of wood he got from somewhere. “Back in the eighties there was a traffic accident – whole family died, really messed the poor guy up. So for some reason, he just decides to start walking – walks north, clear out of Santiago and after a few years makes his way up to here by Antofagasta.

“One day, the fella passes one of those road memorials, you know the ones they put up for the people that died in a wreck or somethin’? (I nodded) Well, by coincidence, the names of his family were written on the memorial, so he figures that’s where his family was killed. Fella up and decides that he’s finished walkin’ for now and just sorta sets up camp there. Been there ever since. I gave him some water and bread once, real weird type, but seems pretty lucid actually.”

Other truckers disagree. “No, he surely wasn’t a doctor. El Ermitaño was an architect!” (said the well-dressed trucker from Chiloé) “Can’t you see that house he’s built? Really a work of art, that house. He once offered to show it to me and it’s got all sorts of really clever nuances and designs. When the wind blows, it funnels right on through a little tunnel he’s made in the back – cools the whole thing down in a few seconds.”

“Interesting,” I admitted. “But how did he get here?”

“It was Pinochet,” stated the Chilote. “El Ermitaño was on TV about ten years back – I saw the interview myself. Apparently, his whole family fell victim to the dictatorship back in the early eighties; they disappeared without a trace and were part of Los Desaparecidos, the thousands of people who simply vanished during Pinochet’s rule.

“Of course, everybody knows Los Desaparecidos were simply murdered and then dumped to rot in some remote place – El Ermitaño knows it too. So about fifteen years ago he hears that a load of bodies had been discovered up here in the desert – of course the poor chap comes right up here to investigate, but doesn’t find anything. Then I guess the tragic unfairness of it all rather got to him, and he just stayed here, hoping one day he can find his family somewhere out there in the desert.”

There are many other versions of the tale of El Ermitaño, but most seem to agree that:

a) He was some sort of professional before he was a hermit. Maybe even rich

b) He lost his family somehow

c) He is in his present location because he is looking/waiting for his late family

I had passed The Hermit at least eight times while hitchhiking around the north of Chile, and his story fascinated me. I had always said to myself or to my driver at the time as we passed his roadside home, “I would love to stop and visit the guy one day.” Unfortunately, the general consensus seemed to be “you shouldn’t.”

“He’s fucking mad,” said one miner. “If he heard your foreign accent he might freak out and knife you.”

“He’s not really mad,” disagreed another trucker from Temuco, “but he certainly isn’t stable. It might not be the best idea to just show up one day.”

Despite the warnings, I still had a wild hair up my ass to spend an afternoon with El Ermitaño de la Atacama. So on this trip north with T, I resolved to stop and see The Hermit at last. I told T the story and she was anxious to meet him as well, and who could blame her – he is undoubtedly a fascinating road myth in Chile whom begs (so to speak) to be investigated. So we stocked up with extra food and water for the old man in Chañaral and hit the road north…off to visit the crazy bugger at last.

———————————————————————-

“Yeah, I know the guy,” said the fat trucker who picked us up at a remote stop about 200 kilometres from the hermit’s squat in the desert. “I’ve never stopped for him before, but I know where he is. Right around kilometre 1,265, I believe it is.”

“Excellent,” said T. “We’ve brought him lots of great food!”

A few hours later the old truck creaked past The Hermit’s desert camp; the peculiar little white house was still there, and the desert was worn flat into little trails in the places he paced every day – including one which led west into the endless desert to a barren mountain (perhaps his family searching trail?). The Hermit himself could be seen puttering around in his heap of rubbish and tires about twenty metres away, up to some secret task. As soon as he saw the truck stop, he jogged over to the driver side and waited for the window to roll down.

“Well, this is it,” said the fat trucker. He rolled down the window and told The Hermit that he had visitors. Though I couldn’t quite distinguish what he was saying as I hopped out of the cab, I heard a loud, rather upset sort of sound come from our reclusive possible host.

“He doesn’t want to see you,” informed the fat trucker as T hopped out.

“Well, we’ll just try and talk with him,” I said as I hiked up my pack.

“Mmmmm…all right.” He shrugged. “Good luck then,” he waved, shoving the truck into gear and driving off. As the semi passed, The Hermit himself was suddenly visible as the trailer rolled by between us.

“What are you doing here?!” he shouted rather frighteningly.

“Um,” I started, “We just want to talk with you. We want to hear your story!”

This was the only photo we managed to squeeze off during all the babbeling. I'm still not sure what that house is made of.

“Noooooo, no no no no no,” babbled the hermit. “No, you don’t understand, you two can’t be here! It’s strictly prohibited!”

“Um,” I looked around, seeing nothing official prohibiting anybody from being anywhere.

“Why?” asked T, then added, “we’ve brought you food.”

“You can’t be here!” repeated The Hermit frantically, apparently well-stocked on food surplus for the week. His wild eyes darted back and forth and he was wringing his hands nervously; all at once he didn’t look so much crazy as he did scared out of his wits.

I tried again.

“Why can’t we be here? We just want to talk to you.” The hermit continued to shake his head and say more strings of no’s. “You seem interesting!” I added in what I hoped was a jovial, friendly tone.

“You can’t be here because I’m –” The Hermit looked around as if there might be someone listening in somewhere in the blank desert, “La Guardia!” (The Guard).

“What are you guarding?” asked T.

“You don’t understand!” said the recluse again frantically. “I’m the Guard for the Curso Menor (Chilean CIA during Pinochet)! They let me be here, but I really can’t let YOU stay here! Don’t you know what’s out there?” the man gestured hysterically to the surrounding desert.

“What?” I asked, starting to feel that this was probably not going to go anywhere.

“Los Desaparecidos!” he hissed. So it was true, I thought. The hermit waved his hands madly in a vague northerly direction, saying, “now, please, leave! Just trust me, you can’t be here!”

I would’ve pressed a little further, but the poor guy seemed genuinely terrified that some shit was going to go down if we stayed in his little spot in the desert. T and I apologized for bothering him and told The Hermit we would be leaving now.

“Just go!” he exclaimed as we left north on foot.

———————————————————————-

T and I walked for a few kilometres before setting up camp in the desert. “You can’t really be too surprised,” said T, sensing my disappointment as we pitched our tent. “Fifteen years in the desert would fry anyone’s brains.”

“Yeah, I know,” I responded as I hammered a stake into the dry desert dirt. “Still, I would have liked to have learned a little bit more. Some of the truckers say he’s perfectly lucid and sane at times.”

“Well, you can try your luck again someday,” said T, rubbing my back. “But I won’t be coming. He sort of gave me the creeps.”

“Yeah, he’s a bit out there, isn’t he?”

“Quite a bit.”

We slept through the night, probably the first people in fifteen years to sleep in the desert so near to The Hermit. I hoped he didn’t see our flashlight in the distance – I wouldn’t want the poor chap to agonize about his safety. And if by some long shot the guy was telling the truth, Los Disaparacidos of Pinochet remained lost – thanks to El Ermitaño del Atacama.

Mission accomplished, I guess…

Chapter 5

Tourist Trap

T wanted to visit San Pedro. De Atacama.

Yeah that’s right – the one you hear about in Lonely Planet when it talks about the north of Chile – the one with all the crazy valleys and geysers and desert, and oh my God, it’s so picturesque and have you seen those postcards? and did you know that there are real indigenous people living there? Yes there are, it’s true! but you probably won’t see too many them who aren’t trying to con you into a hostel for “only” $15,000 pesos a night but on the plus side you’ll definitely meet a lot of German and British and American backpackers wearing stupid hats and chewing happily on coca leaves that they bought for $3,000 pesos a gram and prowling the streets armed with expensive cameras and bottled water and a million only slightly different versions of the same story, their “South American adventure” which has been like, totally the best four weeks of their entire lives and they just want to remember every single moment of it by taking pictures of any sign that has the word “Chile” written somewhere on it and spewing some boring tale about how they actually are not allowed to flush the toilet paper down the toilets here, OMG that’s like, so third world, how do these people even live?

That San Pedro.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s in a really interesting part of Chile, nature wise, and who can blame all the fair-weather travellers for flocking there (much like sheep) but honestly, I’ve passed through San Pedro twice in my lifetime and what I saw did not impress me. It reminds me strongly of Cusco in Peru, which is a beautiful city that has been ruined by hordes of tourists and corrupt locals who can only think about how to make their next Sol.

San Pedro was once just a quiet little town in the northeast Atacama very near to the borders of Bolivia and Argentina; however, one day someone came up with the fantastic idea of Lonely Planet (sarcasm) and ever since then no self-respecting tourist on his South American sojourn has left San Pedro off his itinerary. Consequently the town soon experienced a series of huge changes:

1) Hundreds hostels opened up

2) Tour operators bought most of the commercial space in the tiny downtown

3) Tourists arrived by the hundreds of thousands

4) Things became very, very expensive

5) Most locals who weren’t involved in tourism were forced to move to nearby Calama because they couldn’t afford to pay $1,500 pesos for a kilo of bread

Which brings us to present day San Pedro. There’s only one thing you need to bring to the town to have a magical, unforgettable experience that will stay with you forever and blah blah blah blah – and that thing is:

Cash. Lots of Cash.

Just that, nothing else. Anything more you might require or desire will be forcefully peddled at you for ten times normal price – but you needn’t worry since you did bring your Lots of Cash, right? Good. Now, if you’d like to rent a hostel then just simply wander around the street with your backpack for a minute or two and in no time you’ll be accosted by eight or so people hell-bent on getting you to stay in their hostel, that guy’s hostel sucks. Cool, you’ve got a hostel! All set, Indiana Jones? Great. Now for activities: you can visit Valle de la Luna (tour operators located here, here, here, right there, and that entire street over there), some nearby geysers (you are surrounded by tour operators to the geysers, don’t worry) or even Bolivia (there’s only five tour operators that go to Bolivia, you might have to walk for three or so minutes to find one – I know, I know, it’s ridiculous). Awesome, booked your tour? Got your hostel? Looks like you’re ready! Have a great time, buddy! Oh, and a favor? Here’s $10,000 pesos, could you go pick me up a bottle of water and a pack of cigarettes? Don’t worry about the change – there won’t be any.

ANYWAYS, that’s where T wanted to go, and I told her that it was an expensive tourist trap but she didn’t care and wanted to see it anyways. I finally conceded and said we could go – but we would have to take the hard way there.

There are three ways to get to San Pedro de Atacama: the first, and most well-travelled route goes directly south from Calama. The second, slightly less used route goes west from Calama, passes a few small towns, and then arrives to San Pedro. The last, practically unused route goes from Antofagasta, passing a huge copper mine known as La Escondita (“The Hidden,” which I find ironic since it’s a huge pit that can be seen from space) and later crossing a few hundred kilometres of empty desert before reaching the Salt Flat of the Atacama and San Pedro.

We decided to take the route passing the mine. Once we arrived to La Negra, Antofagasta’s filthy industrial district, we headed straight for the road to Escondita and eventually, San Pedro. Unfortunately once a miner picked us up a few minutes later, we discovered at the security checkpoint that the entire mine was closed down due to heavy snows (yes, Escondita is in the desert, but it’s also very high-altitude and therefore cold). Consequently we were forced to turn back and take the easy route from Calama.

It was a strange day in the desert; I was stunned to see dark clouds on the horizon, and it even rained a few times (though nothing compared to the Carretera Austral). I was a bit annoyed; we came all the way up here to the North to escape from the incessant rains of the South – only to find it had followed us thousands of kilometres to the driest environment on Earth!

“This never happens,” said the couple who picked us up outside of Calama, in reference to the rain. “We’ve lived here in Calama all our lives and it’s never rained so much! The Atacama hasn’t seen a storm like this in hundreds of years!” The couple even admitted that the only reason they were going to San Pedro was to “see the water falling,” as if it was some sort of great natural anomaly.

On the other hand, T and I weren’t so thrilled about the rain. I was still fresh from two wet miserable weeks on the Carretera Austral, and T had also battled the rains of the south in Chiloé and Puerto Varas not too long before. We wanted to be hot, we wanted to be dry, so of course when we hitch up to the Atacama it rains for the first time in centuries. Typical.

Upon arrival to San Pedro I found that it hadn’t changed much since the last time I was there about a year before during my wild illegal jaunt into Bolivia, except for my friend Eduardo had gone back to Coyhaique (apparently he couldn’t take it anymore, good for him). T and I decided to spend two days in San Pedro, perhaps rent some bicycles and go ride across the salt flats or something. It was nearly dark when the couple dropped us off in the downtown area, so we once again needed to find a place to camp (there was no way we were going to fork over $10,000 pesos apiece for the hostel that guy with dreadlocks was offering us).

“I know a few good places where I camped when I was here,” I told T. “They’re over there on the other side of town near the border checkpoint. I found it pretty peaceful.”

“Let’s go, then,” said T. “Tomorrow we’ll wake up early and find some bicycles.”

“Sounds like a plan,” said I, and off we went to my old camping spots by the border control.

———————————————————————-

It was pretty much the same as I remembered it, though there seemed an unusually large number of semi-trucks parked behind the checkpoint. Still, I figured it was nothing so T and I continued along down the road leading to Paso Jama and Bolivia.

This was where things started to get shady. Here I noticed more semis parked all along the road for a few hundred metres, along with a few maraudering groups of young people (in case you didn’t know, maraudering groups of young people are never a good sign).

“Hey, what’s up!” shouted one of them. “Hey, what you got in the bags, huh? Where you going?” T and I simply kept walking, albeit a bit faster now.

“I thought you said this place was peaceful,” whispered T.

“It was when I came here,” I responded, looking over my shoulder. “I don’t know why there are so many people hanging around.”

“Well, I don’t like this spot,” said T. “And I think those guys are following us!”

“Nobody’s following us.”

“Yes they are!”

I looked behind us; it was much too dark to see anything, but she might have been right.

“Ok,” I admitted. “Maybe somebody’s following us. Here, quick, slip down into the bushes over there and we’ll see if anyone passes by.”

We did; after ten minutes or so nobody came.

“They could be waiting for us to come out,” said T, still looking down the road.

“I don’t think so,” I said, sitting down. “I think we should just make camp here. No-one will see us in the dark behind these bushes.”

“I don’t like this spot,” T said again. “They might just be waiting for us to get settled, and then they’ll come for us while we sleep!”

“I really don’t think that will happen.”

T gave me a dirty glance. “Look, you’re not on your own here anymore! You’ve got a woman with you, and things are a lot more dangerous for women.” She looked down the road once more. “I want to leave.”

I sighed. She was right, of course. Some things would have to start to be done differently now that there were two of us. I gave in and we decided to return to the town to find a more well-lighted place to camp…just in case.

T didn’t want to pass by the leering young people again, so we made our way through the desert bushes in the darkness until we popped out on a small street a few blocks away from the police checkpoint.

“Let’s try asking the border police,” advocated T. “Maybe they’ll let us set us camp behind them.”

We went and tried, but the official didn’t even bother letting T finish her sentence; after her heard the word “camp” he immediately shook his head and closed the window.

“Let’s try some restaurants,” said I, so we went to five or six locales in the area, with nothing but negative results. Apparently free camping in San Pedro is not as easy to find as one might think, though we did get pointed a number of times to a place down the road that charged $5,000 pesos just to pitch your tent (no way).

Eventually we settled for a spot in the semi parking lot very near to the border police. We figured that the worst the cops could do if they saw us was tell us to leave, and maybe by the time they noticed us we would have gotten a few hours sleep, anyways. I worked setting up the tent between two trucks from Paraguay while T went to the bathroom to brush her teeth.

The parking lot had horrible soil for setting up tents; it was 50% dirt and 50% stones and little rocks, making it nearly impossible to hammer the stakes down into the ground without bending them. After fifteen minutes of frustration I managed to get the stakes partway into the ground. They still weren’t very secure, so the tent drooped and sagged like elephant skin. I sighed. It may be elephant skin, but it would have to do. T came back shortly, and we crammed ourselves and our packs into the little tent and slowly fell asleep.

The next morning we awoke to the sounds of truck engines rumbling and huge tires rolling about, and we woke up pretty quickly so no-one would accidently run us over while pulling out. When I unzipped the tent, an odd sight greeted me:

All of the trucks from the night before were still there – and not only that, but there were even more. Semis were shoved and parked into every tiny space available, while the drivers simply stood about. I looked at my clock; it was ten am. Why hadn’t they gone out to cross the border yet? Something was definitely up here at Paso Internacional San Pedro.

T stuck her head out the tent, blinking dreamily. “Lots of trucks here,” she observed.

“Too many,” I said. “Sure is a strange day.”

T left to go wake herself up in the bathroom as I surveyed the scene around me. There were truckers everywhere, from everyplace; Chilean, Argentine, Paraguayan, Peruvian, you name it. All of them seemed not to be doing anything particular, just sort of standing around, sipping maté, and smoking. One of them gave a friendly wave to me as I pulled out my sleeping bag from the tent. I waved back with a grin and began breaking up camp in a light, jolly mood.

This part of San Pedro I actually liked – even though it wasn’t particularly campable and even though there was a big pool of stinking septic-tank water just twenty meters away – here I felt at home. Truckers nodded and said hello to me at me as they passed by with a fresh pack of cigarettes – here I was a familiar face indeed: the common wandering gypsy, usually found hanging around anyplace truckers are. Any hauler will know my type well – we’ve packs, tents, maybe a ragged bundle of some trinkets we sell or a wizened guitar with a broken E string. Half-smoked cigarettes are tucked behind our ears and matted hair frames our hopeful smiles – the smile of the career hitchhiker, for one can never stop smiling when you’re in the business I’m in.

In general the trucker is a friend of the gypsy – after all they lead similar lives, the only difference being that the trucker gets paid for his travels and he has a bed to sleep in most of the time. Most will greet the wanderer with a smile; he may not help, but he certainly will not mistreat, for to disrespect a fellow traveller means to thumb your nose at the Gods of the Route – and if there’s anybody who’s worried about what the Gods of the Route might think it’s the average truck driver.

This is one of the leading reasons that I (and T for that matter) have such great respect for the camioneros of the world; the hardworking trucker will help the stranded hitchhiker after ten thousand normal drivers do not. The smiling trucker will offer his bunk bed or at least his passenger seat if the weather outside is miserable or there’s no good place to camp. The jolly trucker will share his dry crackers and ham and half a Coca-Cola, while the restaurant owner turns you away on an empty stomach. The boisterous trucker, the long-winded trucker, the stony-serious trucker, the nomadic trucker…they all are a friend of mine.

I was nearly finished packing up when a Paraguayan trucker toting a yerba mate came up to me, introducing himself as Gerardo.

“Patrick,” I said, taking his outstretched hand and shaking it.

“Nice to meet you, Pateeks,” he said, smiling. “I noticed you and your lady camping out here last night – was it very cold?”

“Not particularly, though we did have some issues getting the tent set up.”

Gerardo laughed. “I noticed this.” He offered his mate. “Yerba?”

“Please,” I said, accepting the mate and sipping up the hot, bitter liquid inside.

“Where are you and your…girlfriend? (I nodded, still sipping) travelling to?”

There was a loud slurping sound as I finished the mate. “We’re headed up to Iquique after this,” I said, giving the mate back.

“Ahh, to Iquique, that’s good. I thought you were off to cross the border.”

I shook my head and pulled up the last strap on my pack. “Not today, though I’d like to. We’re just headed north.”

Gerardo nodded. “That is good. I thought you two were stranded here like the rest of us!”

I raised an eyebrow. “Stranded? How come?”

The trucker gave me a look. “You didn’t know? All the international passes have been closed for two days because of the snow!”

“Really?” I said, and looked around once more. “So that’s why there are so many of you here.”

Gerardo nodded again, refilling the mate from a small thermos he had tucked under his arm. “Yes, two days we’ve been here. Quite annoying, actually. I was supposed to be in Asunción by this morning.”

“Yeah, well, can’t change the weather, can you?” I answered, putting on my pack.

“I suppose not,” said Gerardo, staring up at the pass, which now that I looked at it I noticed was covered in a thick blanket of white. We stared in silence at the pass for a few moments. What a nice guy, I thought to myself. Just wanted to know where I was going, and gave me mate. A perfect example of what I was just thinking about truckers.

There was a loud sucking sound as Gerardo finished his mate. “Well, I’ll leave you to your business,” he said, smiling again. “Good luck in Iquique, and if you decide you’d like to go to Paraguay I’ll probably be here another few days at least. Let me know and I’ll take you both, no problem!”

I beamed; my theory was all but perfect. “Appreciate it, Gerardo! Good luck, and thanks for the mate!”

“No problem! ¡Que te vaya bien!”

“¡Tú también, compadre!”

We shook hands once more and went our separate ways. God bless ya, Gerardo, I thought, smiling as I walked back to the town, happy at least to have found one part of San Pedro I liked. Keep on affirming my faith in the goodness of truckers. May the rest I meet be as good as you.

__________________________________________________________________

T and I found a couple of bicycles to rent for our one day in San Pedro, costing $5,000 pesos for the two of us to go out all day – not actually a bad price. We wanted to go to the salt flats, but it was an extremely windy day and the salt flats were a good haul, so we decided to settle for the nearer

Valle de la Luna. Though we didn’t go all the way there (we stopped to visit some archeological ruins, but ended up not going in since they wanted to charge $10,000 pesos for the two of us, and the whole thing would have lasted only thirty minutes anyhow). We still had a great time, finding our own

nice little spot in the desert after stopping for lunch in a secluded canyon off the road. There were many interesting rocks and even some old bones there, and we even came across some extremely soft sand which we found perfect for napping. I hadn’t really been very excited to go to Valle de la Luna anyways, especially after we were passed by at least fifty vans full of

tourists on the way there while cycling down the road. In fact, I was much more pleased with our quiet little canyon – we didn’t see a single other person there.

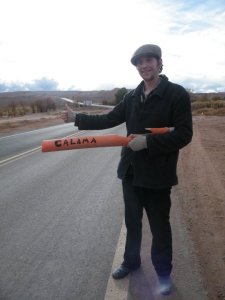

When we got back to San Pedro, zooming down the hills leading into the town at alarming velocities and without hands, we immediately began hitchhiking back to Calama so we could head to our next destination: Iquique. I made a sign out of an old construction reflector and T gave her prettiest smile; soon we were vrooming back north, ready to take on a little route I called “The Salt Flats Highway.”

Chapter 6

The Salt Flats Highway

It runs, according to Google Maps, northeast from Calama across two huge salt flats before coming to a little railroad town on the border of Bolivia called Ollagüe. From there it enters true Chilean wilderness, traversing two more salt flats and a whole lot of absolutely nothing – 450 kilometres of unforgiving, high-altitude desert where not even bunchgrass can grow. Obviously, T and I were anxious to hitchhike it and so there we stood in failing daylight trying our damndest to hitch northeast out of Calama.

Calama isn’t the safest city in Chile, so we were becoming rather anxious as the sun dropped like a stone below the auburn eastern horizon. Finally, just a moment before dark, a hired driver on his way 30 kilometres down the road to pick up a couple of businessman in Chiu-Chiu pulled over and drove us there.

When we arrived, T and I were at a loss as to what businessmen were actually doing in Chiu-Chiu. A microscopic little town on the edge of nowhere and the cusp of somewhere, Chiu-Chiu was San Pedro without the tourists. San Pedro without the hostels. San Pedro without the shops and tourism agencies. San Pedro without the crud, basically.

We found it spectacular.

After stopping in a local eatery for a bit of dinner we decided to find a place to make camp, which would surely not be as problematic as in San Pedro. We asked an old gentleman selling sopaipillas outside an ancient adobe church if there were any parks or good camping places around; he told us to knock at the rural hospital, whom apparently had a nice little play area out back that would do all right for a night of camping.

We went to the hospital (known as a posta rural in Chile) and knocked lightly on the door. A young man in his late twenties answered.

“Yes? How can I help you?” he said, leaning against the doorframe.

T started out. “That gentleman over by the church told us to knock here. We were looking for a place to camp for the evening, he mentioned something about a playground out back?”

The man smiled and said without hesitation. “Ah, so you’re camping, are you? Well, it’s no problem, you can camp back there for sure!”

We were rather taken aback; such generosity, and without a moment’s hesitation!

“Really?” I said. “It wouldn’t bother you, would it?”

The man waved his hand dismissively. “Not at all! In fact, I would invite you to stay inside, but I’ve only just started working here and I don’t want to begin taking liberties so quickly. Come in, come in!” he stood aside and beckoned. We went inside as the man went to the kitchen and started rummaging around some bags.

“Are you hungry? Would you like some coffee and bread?”

Unfortunately, we had just had our nightly coffee and bread. “We’ve already eaten,” said T, “but thank you!”

The man looked at us. “Are you sure? I’ve got cheese!”

“Really, we couldn’t possibly eat another bite,” I said.

The man shrugged and started digging around in another bag. “How about some fresh fruit and yogurt for the night, then?” He thrust the food into our hands. “It’s cold out there – better keep those vitamins up!”

T was beaming as she took the food from him. “Thank you so much!”

“No problem, really! I’m Mario, by the way.” He held out his hand and I shook it. “I’m the paramedic on duty here in Chiu-Chiu.”

Introductions were made, a few stories were told, and then Mario the paramedic showed us to the playground out back.

“You can set up your tent anywhere you like! Looks like there’s some good flat space over there by the slide.”

“It’s perfect, Mario,” I said. “Really, we appreciate you being so accommodating! I feel like I’m in the South again!”

Mario gave a wave as he went back inside. “Don’t mention it, really. And when you wake up in the morning come knock on the door, I’ll make you two breakfast!” He disappeared inside and shut the door behind him.

T and I began setting up the tent near the slide while a pair of local dogs who had been following us for the past hour thumped their tails and watched on curiously, goofy smiles on their furry faces.

“You know,” said T happily as she scratched one of the hounds behind the ears, “We’ve only been here a few hours and I already love it a hundred times more than San Pedro!”

“We’re in agreement,” I said, hammering in the last stake, which sank in easily and stayed firm. Heaven.

———————————————————————-

The morning brought sounds of barking dogs – our friends, valiantly defending our campsite from other apparently undesirable passing strays. T was thrilled our companions had stayed the night with us, and was sure to give them lots of love as we packed up camp.

There’s one thing you should know: T has a thing for dogs. All dogs. In fact, she loves them so much that she oftentimes avoids giving them attention for fear of becoming too attached and then getting her heart broken when we inevitably have to continue on. But these two dogs in particular were so sweet, (“They stayed with us the whole night,” cooed T as they furiously licked her face) that she broke down and loved the fur off them.

I tried to tell her to go away since I was putting my boots on...but who can say no to such a shameless sap?

We went back to Mario’s door and knocked, good and hungry in preparation for the promised breakfast. Our two canine companions waited expectantly beside us, perhaps wondering if they would get breakfast, too.

“Come in, come in!” said Mario as he opened the door. “Coffee or tea?” he said as we sat down to what looked like a delicious, healthy start to our day. He was a paramedic, after all…

As we ate wheat toast with real cheese (not the cheap supermarket kind), we chatted with Mario and enjoyed the feeling of hot coffee warming our cold bodies.

“I’m from just down the road, in Calama, but I’ve been here in Chiu-Chiu for a few weeks now. So great, this place. Very peaceful, though we do still get the occasional heart attack every now and then.”

“Yeah, I’m sure it’s pretty different from the overdosing junkies you get in Calama,” I said, swallowing another bit of scrumptious bread and cheese.

Mario nodded solemnly. “It’s a very big problem in Calama – the drugs. We’re so close to Bolivia the city is saturated. Really terrible, the whole thing.”

In Chile, the posta rurales operate on a no-pay basis, which is very different form the way proper hospitals do things in this country. In the postas, anyone, from anywhere, in entitled to free medical treatment and any medicines that are available, similar to the way they do things in Bolivia. The sacrifice is that the postas are not equipped with proper doctors (only paramedics), or operating facilities. These can only be found in large hospitals which run on a system similar to that of the U.S., only not so bad. Still, I loved the idea of the postas.

“People come in for check up’s all the time,” said Mario happily. “In the city a check-up can cost you at least $5,000 pesos if you’ve no insurance, and a lot of times we can isolate a problem with the health here free of charge – then the patient can seek out a doctor at a hospital.” He shrugged. “It’s just a better system that way.”

“So I could even get a free check-up here, even though I’m not a Chilean citizen?” I asked.

“No problem! We could even give you free medicines, so long as they’re not anything too hard to find. We have all the basic things here, Penicillin, Ibuprofen, Amoxicillin – the lot.”

“Incredible,” I said. “I wish they would establish some postas in the States. It would really help out a lot of people.”

“They don’t have them in the States?” asked Mario, looking slightly taken aback.

I laughed bitterly. “In your dreams. The only way you’ll get a free checkup there is if the doctor is planning to harvest your organs afterwards.”

“How awful!” exclaimed Mario. “The postas are a great thing,” went on the paramedic, stirring his coffee. “Just this morning one of the old men came in with a nasty eye infection. I gave him some drops and a patch, told him not to go out too much, and he’s going to be fine! The poor fellow could never afford to pay for treatment, what else is he supposed to do?” Mario thought for a moment, then said, “How much would that cost in the States?”

I thought for a moment. “Well, first you’d have to go in for a checkup, and if you’ve no insurance, that’ll be at least $30. Then they’ll probably send you to a specialist (hundreds of dollars for sure) and then you’ll have to buy the drops, which will probably run you at least forty more bucks. So all in all…” I calculated in my head, “probably about $350.”

Mario was silent for a moment. Finally, he said somberly “If that was the case here in Chiu-Chiu, my friend here would have probably lost his eye.”

We ate quietly for a minute or two. Then Mario said, “Well, if you two need any medicines before you go, just say the word! All you need to do is sign your name!”

T and I got some Ibuprofen before leaving, in anticipation of headaches in the high altitude places the Salt Flats Highway was bound to take us. Mario gave us a little extra bread for the road, and we were off – but not before walking around the town and getting to know it a little better in the daylight.

Interesting fact: Chui-Chiu is home to the oldest church in Chile. While I’m far from a churchgoer myself, we went inside for a moment to pay our respects and find out what the inside of a 400-year-old church looks like.

Our canine friends of course followed us around Chiu-Chiu the entire time, and when we began walking out to the road one trotted happily alongside us all the way to our hitchhiking spot, where we waited outside a carrot farm for our next ride into the wilds.

Chiu-Chiu is known in the region of Antofagasta for one thing and one thing only: carrots. Lots of carrots. While we waited, T and I watched a group of five or six people working around a large but simple carrot-cleaning machine. It worked like this:

- Carrots go in one end.

- Carrots are soaked with water

- Carrots are tossed and knocked around on a conveyer belt

- Carrots come out the other end, are bagged up, and sent to Calama.

I went over and offered to buy a couple of carrots for T and I, but the guy, after staring at me for a moment, simply smiled and handed over a few for free. T and I found them to be some of the sweetest, most delicious carrots we’d ever tasted. Reason number 47 to love Chiu-Chiu: Carrots!

The morning wore on as the thin traffic on the Salt Flats Highway flittered by, mostly mining trucks headed to one of many small copper and gold mines in the desert. Our dog was still happily spending time with us, much to T’s utter amusment.

“Want a carrot?” asked T as the pup grinned blankly at us from the middle of the road. T tossed over a piece, and the dog crunched it down like it was a cut of filet mignón.

“She loves carrots!” said T happily, breaking off another piece and tossing it over. As soon as the carrots were all gone, T got out some bread and salami and began feeding the dog that, too.

I sighed. “Do you really have to give all our food to the dogs? She’s already had half a carrot.”

“But just look at her!” purred T as the dog whapped her tail in the gravel. “She’s so happy to be with us! And she stayed with us all night.”

I rolled my eyes. This wasn’t the first time T had taken a little off the top of our food surplus for the dogs. It had happened in Chañaral, Bahía Inglesa, La Negra, Calama, and now here. I heaved another sigh – she was a hopeless.

“Oh, come on, not the meat!” I said as T went for our ham deposits. “Who knows how long it’ll take to get to Ollagüe! We could need that energy!”

“Oh, hush. It’s just one slice,” retorted T as the pup slurped down an entire piece of ham. There goes a sandwich, I thought.

“All right, all right,” I said with the air of someone who knows he’s not going to win. “But don’t come complaining to me when we’re in the middle of nowhere and you’re hungry.”

“It’ll be worth all the good karma,” grinned T as the dog whimpered and pawed at her leg. She gave the pup a gooey look and started to go for another slice.

“Come on, seriously, no more!” I begged.

“Okay, okay…” she put the ham back in the bag; I relaxed slightly. Then she suddenly said brightly, “How about some bread, then?” I sighed as the dog licked T’s hand, as if saying, Yes! Yes! Bread is good!

One bread later, the pup seemed stuffed to the limit with our road goodies, and rolled over in the sun to sleep off the food intoxication T had brought upon her.

“There, now she’s happy!” exclaimed T merrily. “Oh, come on,” she said, seeing me counting the number of hams we had left. “We’ll have plenty, you’ll see!”

“I hope so…”

Finally around eleven, a miner truck stopped and drove us out into the wilderness. As we drove off with our packs in the bed, I suddenly heard, as I was introducing myself to the driver, a small squeak come from T.

“What? What’s the matter?” I asked, concerned. T seemed on the verge of tears as she pointed out the back window. I looked.

The poor mutt we’d left on the road was running, running as fast as she could to keep up with the quickly accelerating pickup. “She wanted to come with us!” moaned T quietly. “Poor girl!”

“Oh, don’t worry, she’ll be fine,” I said consolingly. “She’s just upset all her fresh ham is headed to Ollagüe without her.”

T was in a silent mood for the rest of the ride. When we got off at a remote gold mine about 150 kilometres from Ollagüe, T hugged me and vowed never to make friends with dogs ever again. It was simply too heartbreaking, apparently.

“Does this mean we get to keep the rest of our ham?” I asked.

“Shut up,” she grumbled. And with that, T and I began our walk still further down the Salt Flats Highway, in hopes of finding a good hitchhiking spot at the bottom of a nearby canyon a few kilometres ahead.

The canyon afforded cover from the incessant wind and a few spots of shade, but the hitchhiking was far from good. The traffic was extremely light, and what vehicles that passed seemed to be jam-packed with people, mostly miners. In mid-afternoon a pickup finally took us in the back about eighty clicks further down to yet another mine – this one an aboveground borax mine on the Salar de Ascotán, the first salt flat on our highway.

The mine was one of the sorts that would probably transform into a town, and maybe one day a city. The salar stretched out to the west over to the Bolivian border, and the camp was lodged into the side of a canyon on the western horizon. While we’d rode in the back of the truck T and I had gotten extremely cold, and I was wearing four of my jackets, while T occupied the last one, as she had only brought three jackets. As the sun sank down so did the thermometer, and the wind howled through the altiplano as we sat in a huddled mass on the side of the dusty dirt highway.

To pass the time we played “Stones” and watched the miners play a few intense games of soccer on the salt flat; no matter where you go in Latin America, if there’s people, there’s definitely a soccer match being played somewhere close by. I smiled as one of the players scored a goal and the entire group went bananas, their victory shouts the only sound echoing off the lonely mountains.

After dark we found ourselves still stranded. Earlier I had made friends with one of the miners while waving around a huge cardboard sign I had made during our wait in the canyon, which read, “SU DESTINACIÓN ES LA NUESTRA!” in great bold letters. Your destination is ours! The miner had paused for several seconds while reading it, then gave a hearty laugh and waved me over. Turned out he was the boss, and told me that if we were still stranded by nightfall to go up into the kitchen for some dinner and a bed for the evening.

Well, we were still stranded, and it was after nightfall so T and I hiked up the little dirt road to the mining camp and found our way to the kitchen, where the cook gave us funny looks and served us, you guessed it, coffee and bread.

As we ate our dinner in silence the rest of the miners came into the mess hall for their supper, bowls outstretched. They huddled around the one television in the whole mine as they occasionally stole curious glances over their shoulders at T and I. Eventually one came up to talk to me, and I learned that most of the miners that were working there were Bolivian. They were all very outgoing amongst themselves but seemed reluctant to sit near us, cramming themselves around one table even though there was plenty of space on our bench.

Finally came nine pm, when they shut off the electric generator that powered the mine for two hours after dark. The miner who talked with T and I procured a mattress from somewhere and set it up in the mess hall near the silent TV. He pointed, smiled, and left, shutting the door behind him.

“I guess we sleep here,” I said, unpacking my sleeping bag. We passed a rather cold night there in the mess hall of the Borax mine, but it surely would have been worse in our tent out in the cold winter winds of the altiplano.

______________________________________________

The next morning we were greeted with hot coffee and more curious but silent glances from the miners as they filed through for their morning coffee before beginning work in the mine. T and I left around eight, hoping to make the last seventy clicks or so to Ollagüe in short notice.

There were few vehicles headed so far as Ollagüe that weren’t buses, so we were left with a choice: try to hitchhike all day and possibly arrive to Ollagüe taking the chance of getting stuck at the mine again, or take the morning bus for $1,000 pesos the rest of the way. I was in favour of waiting all day and risking getting stuck, but T wanted to take the bus so we could get started on the most remote sector of the route as quickly as possible.

“It could take us a solid week going north from Ollagüe,” reasoned T to a disagreeable nomad who really, really hates buses. “Why lose another day being stuck here? We’re still not in the wilderness yet, you know.”

“Yeah, but why wait all day yesterday in the canyon and sleep at a mine if you’re just going to take the bus the next day? Seems pretty pointless, if you ask me.”

“Seems pretty smart, if you ask me!” retorted T. “Like you said before, we’ve only got so much food, and who knows what we’ll be able to buy in Ollagüe. The food that’s there is bound to cost a lot since it’s so isolated.”

“I want to hitchhike,” I maintained. T gestured exasperatedly down the road.

“Hitchhike on what? There’s no cars! And anyways,” she said, playing on her knowledge of how I think, “wouldn’t you rather be stuck in the wilderness instead of by a mine?”

“Mmm,” I grumbled.

“Well, stay here if you want,” said T briskly. “I’m taking the bus, and I’ll see you in Ollagüe in three days.”

“Fine,” I conceded. “We’ll take the dumb bus. But just this once – this highway is far too beautiful to be seen from the greasy window of public transportation.”

And so we took it, I’m ashamed to say. It was just as horrible as I figured it would be, packed with poncho-toting tourists and windows so foggy I couldn’t see a thing of the next salt flat we passed. Also there was a fat Bolivian guy snoring loudly next to me and breathing sickly into my ear.

We arrived to Ollagüe in half an hour or so; I was in a rancid mood on account of the bus, but one thing did make me happy: T and I were the only people who got off in Ollagüe – and seemed to be the only people actually in Ollagüe.

If you want to know what Ollagüe looks like, just picture a typical Old-West ghost town: the only sound is wind blowing, dust is everywhere flurrying up into little mini-tornados, there are rows of old dying houses with no signs of life – and the whole thing has a railroad going through it.

The railroad is the only reason Ollagüe actually exists. It’s the stop on the Chilean side for trains going to and coming from Bolivia – therefore the entire town just sort of feeds off the trains that pass through. There are no passenger trains – only freight trains, an exciting fact I quietly noted for a future day of trainhopping.

T and I went to look for place our little dirt highway continued into the nothing but surprisingly had a hard time. Ollagüe seemed to have only one road leading out of it, and that road went to Bolivia. Though I would have loved to revisit Bolivia, most of you probably know that if I go back there they’ll throw me into prison for awhile and then, if I survive that, fly me back to the States. Don’t want that…

We managed to locate the local law enforcement and went inside the station to ask for directions.

“Hello, hello, how can I help you?” said the policeman on duty as we entered.

“We need directions,” I admitted.

“All right. Where are you going?” he inquired with a clipped, official sort of accent.

“Iquique.”

He stared. “Iquique?”

“Iquique.”

The cop scratched his head. “Well, I’m sorry to say, but you two seem to have gone a bit off course. Iquique is on the coast. You, my friends,” he pointed vaguely east, “are almost in Bolivia.”

“We know where Iquique is,” said T. “There’s another road, it goes north and into Pica. From there we’ll go to Iquique.”

“Pica? Well, you’re quite far away from that as well.”

“We know,” I said. “Could you please just point us to the road?”

“Hmm, road north?” he scratched his head again. “I’m sorry son, but…erm…there is no road north from here. Just the one east to Bolivia.”

“But I saw it on the map!” I protested. “It winds along north from here, passes some salt flats, and arrives to Pica after a long time. Number…ah, I can’t remember. Have you got a map, I’ll show you.”

“Uhm,” trailed the cop, “I’m not sure. Let me go and check.” He disappeared out back for a moment.

I rolled my eyes. “He must be new.” T giggled.

The officer came back a moment later…without a map.

“So?” I said. “You must have a map back there somewhere. You’re the police.”

He scratched his head. “Well, we do you see, but…”

“But what?”

The officer stared me straight in the face and said nervously, “You can’t see our map.”

I stared. “Why can’t I see your map?”

“Erm…” he rubbed his neck. “It’s…erm…a secret map.”

“A secret map?” said T with a sigh. “Really? Are you searching for treasure or something?”

“No!” said the policeman. “It’s got all of our strategies for in case the Bolivians invade!” He crossed his arms. “You’re not allowed to see it.”

I laughed. “We’re not Bolivian spies, you know.”

The cop shrugged. “Doesn’t matter. You still can’t see the map. Regulations prohibit it.”

I ground my teeth. Regulations, I really do hate that word. “Look, we’re not going to photograph your silly map, we just want to point out to you the road we’re looking for. It’ll just take a second.”

He hesitated, thinning his lips. “Let me ask my commander first.” He left again, coming back a few minutes later with a policeman wearing an official-looking hat – obviously his commander. They carried with them a large map glued onto Styrofoam, with little flags and lines drawn on it. How professional, I thought.

“All right, show us where you want to go,” said the commander. “Make it quick, this is a –”

“– secret map, we know,” said T while I looked for the road.

“Look here it is!” I pointed to the thin yellow line leading north. “Road number A-62. That’s the road we’re looking for!”

The officer studied the line, then looked back at me and stared.

“A-62? You want to take A-62?”

“That’s right,” said T.

He laughed. “I’m afraid that’s quite impossible.”

Impossible, I’d heard that one before. “How come?” I pressed.

“Well, A-62 no longer exists. It has been abandoned for about sixty years.”

Silence. Then T said, “Abandoned? How come?”

“Well, there was a sulfur mine a few hundred kilometres north of here back in the thirties and forties, but in the early fifties it…erm…rather ran out of sulrfur.” He blew his nose. “So the road closed, the mine was abandoned, and that’s that. No more A-62.”

“No more A-62,” I trailed. “So it’s completely gone?”