Somewhere in Western Pará, Brazil

I can tell when there’s a hole in my mosquito netting that needs repairing when I spot three or four bloated females buzzing sluggishly around in the space underneath my hammock after waking up in the morning. They can find their way in, but never back out. This, at least, gives me the satisfaction of systematically squishing them one by one and stymieing their reproductive efforts, leaving little spots of blood on the netting where they met their demise at the tips of my fingers.

Like the Medieval English hanging pirates to rot in the sun at the entry to their seaports, these serve as warnings to future violators of my sleepy little hammock world. Also like the pirates of the latter-day, other mosquitoes take no notice of these caveats, and continue to seek out flaws in my netting throughout the course of the night, forcing me to keep it in good condition.

Forget the wheel, the cotton gin, and the iPhone; the mosquito netting is man’s greatest invention. I cannot describe to you the satisfaction I derive from shining my flashlight up into the cross-hatched veil and seeing hundreds of mosquitoes and numerous other blood-sucking insects bouncing pointlessly off the barrier, their access to my sweet, nutrient-rich blood cut mercilessly off. It’s like tying up a hungry dog and putting a juicy T-bone just out of reach; they’re just (ahem) itching to get at me. Several times, I’ve given a devious chuckle and pointlessly flipped them off; they respond by continuing to be mosquitoes.

It was with relief that I stepped off US Airways Flight 1986 and back onto Brazilian soil in Rio de Janiero. The relief was greater still when my passport and visa were stamped with no complications. The 12-hour layover at the airport between flights was mostly uneventful, with the exception of when I changed 436 Argentinean pesos (a gift from my grandfather) to reals and got almost R$900 back. This, according to my recipt, was a huge mistake on the part of the exchange guy – he had accidentally punched “dollars to reais” into his computer instead of “peso (ARG) to reais.”

Despite the fact that 900 reais is a huge amount of money that I could have definitely used, I knew the exchange guy would probably have to pay the difference. After about an hour of intense moral deliberation, I went back to the exchange office and showed him his mistake. He was, understandably, hugely relived I hadn’t split for Belém with a whole bunch of his cash. I will admit that I came very close to doing so; I could have done so much with that money. Still, it’s only paper – and anyways, the loveliest things in life are free.

The bright side was I was heading back to Belém with about R$140 and an extra laptop for sale – which was a hell of a lot more than what I had left it with. TAM airlines flight 392 to Belém was delayed in Rio for a good two hours, so by the time I finally arrived to Val-De-Cãns International Airport on the shores of the Pará River it was around three in the morning and I was exhausted, having been running on insufficient airplane sleep for the past two days. I stumbled out of the jetway and collected my pack from the baggage carousel, checking to make sure TSA in Charlotte hadn’t confiscated my machete, hatchet, pocket knife, and other items that might have been deemed an unacceptable threat to National Security and the governor of North Carolina.

Appropriately, it was raining in Belém. The tropical air felt wonderful on my skin after a whole December in the northern hemisphere. I checked to see if the knife and fingernail clippers I had buried by the bus stop the month before were still there; not surprisingly, they were gone. I hoped their new owner was treating them well. Walking across the street, I pitched my brand-new tent in the middle of the traffic circle and went to sleep. Back on track, I thought to myself. Now, where was I…?

———————————————–

According to my brain and memory, I wanted to go to the Guyanas – and had been working my way there for the past five months from the Chilean capital. In Belém, I was just a hop and a skip away from French Guyana; unfortunately, you have to hop across the 200-mile wide Amazon delta and skip through malarial swamps and uninhabited islands. And no, there are no roads or bridges. The way I saw it, I had four options:

- Pay about R$80 for a boat to Macapá, the city on the north side of mouth

- Wait in Belém and see if I could hitch a free ride on a boat to Macapá

- Hitchhike thousands of kilometres west to Manaus on a notoriously bad dirt road in the height of the rainy season, and enter the Guyana Shield vía Guyana

- Hitchhike along this same notoriously bad dirt road during the height of the rainy season to some remote location in the Amazon Rainforest, where I would build a raft out of balsa trees and float with the current to Macapá whilst whistling the fiddle duel from The Devil Went Down to Georgia and hallucinating in the throes of malarial fever.

The obvious choice, you’ll be unsurprised to learn, was Option Number One. I paid R$80 and was in Macapá 24 hours later, happy with the safe, easy journey, and having met some lovely English tourists on the boat ride there.

Haha! Just kidding; you should’ve seen your face! The clear choice, as we all know, was Option Number Four. English tourists…as if!

——————————————–

Fast forward to a few days later. The streets of Belém had not changed much, though the temporary evangelical bookstore had been taken down, and the homeless harmonica guy had forgotten about me. Gabriel was still there in his hut, having made a new wooden airplane to replace the one I had bought.

Back in the US, I had been generously resupplied by my Dad and Gander Mountain with a myriad of equipment that I figured I would need for my upcoming adventures in the Amazon. These, among other things, included a cut down Tramontina machete, Gerber hatchet, great lengths of rope, some fishing gear, boots (my Dad’s own alert boots from his time as a KC-135 pilot in the Cold War), heaps of socks, an old Air Force helmet bag, and a bivvy tent.

I was happy to have gotten a tent in the US – which, since coming back to Brazil, has proven invaluable in urban squatting environments, where suitable posts in safe locations are sometimes hard to find. I set it up in the Praça da República right where I had hung my hammock before; I could still see the marks in the ground where the bookstore had stood for Christmas.

Tents are few and far between in the tropics, and I soon realized there is a good reason for this: they get hot. The cool breeze you feel in the hammock is blocked by the fabric, and you have to keep all the hatches battened down due to likely rain. Still, this was the price I paid for a shelter that did not need trees or poles to be set up, and provided more security for my belongings as I slept.

On the third night of tenting in Belém I was reminded of the first fundamental rule of tent-squatting in public places: look before you pitch. The revulsion I felt the following morning when I realized I had slept all night long with just the bottom of the tent separating me from a steaming pile of fresh human shit (I could tell it was human because there was toilet paper mixed in) was indescribable. And when I had to try and wipe it off with a handful of grass?Gua! Absolutely appalling! Weeks later, the smell still lingers…

I had remained in contact with the locals who had given me the “tour” of Belém at the docks, which proved to be a good move on my part; after the shit evening in the plaza I was invited to stay at their respective homes, where I remained for two days planning my river voyage. First I stayed with Sergio, who is openly gay and spent the evening watching chick flicks and crying intermittently.

“It’s okay,” I said consolingly as Sergio sniffled into his pillow. “I’m sure Ryan Gosling will get back with that rich lady in the end.”

Sergio mumbled something that sounded like “mimerabaflpft,” and we had to pause the movie for a moment while he went into the bathroom to wash his face.

The next night I stayed with Byron, a young man about my age just finishing up college. He lived with his family in a nice home in the suburbs of Belém, and the whole group drove me around for awhile to see other nice places in Belém that were not in Cidade Velha. I received vague visa advice from Byron’s Dad, who works for the Polícia Federal, then, like always, vanished down the road, leaving behind promises to visit again that I didn’t know if I would be able to fulfill.

————————————————

Rodoviária Trans-Amazônica – or the “Trans-Amazonian Highway,” as it’s known in English, starts in northeastern Brazil and crosses the majority of the Amazon rainforest, winding for thousands and thousands of kilometres through the jungle before coming to an end in the middle of nowhere somewhere near the Peruvian border. Starting in Marabá, the pavement ends and the BR-230 turns to dirt – or in the case of the rainy season, quagmire.

English Wikipedia offers little encouragement to the hopeful rainy-season hitchhiker, calling the road “inpassable” between the months of October and March. Spanish and Portuguese Wikipedia offer more information but still agree that rainy season travel is a no-go. A random website I found listed the route as “the worst in the world,” and had many photos of 18-wheelers being swallowed up by huge pits of liquid mud.

So basically, don’t go on the road between October and March.

The fact that I am writing this in February from Itaituba, about 2.000 km down the Trans-Amazonian highway, just goes to show you shouldn’t believe everything you read on the Internet.

—————————————————————–

Me with my free shirt in Inhagapi and the man who gave it to me. The story goes as such: I was hitchhiking. The man picked me up. He is president of a local political campign. I get a free shirt supporting the campaign. It says "Fala Inhagapi!" on the back and "Um partido decente" on the front.

Wanting to take a different route to Marabá than the one I had taken to get into Belém back in December, I wandered my way south along the muddy back roads of the tropical state of Pará. I got very dirty and wet (it is the rainy season, after all), was stopped by a river on a few occasions, had somebody give me a free T-shirt, got lost and did some backtracking, ate lots of açaí, crossed several more rivers on ferrys, received 8,000 mosquito bites, and wandered around some more. Three days later I made it to Novo Repartimento, my starting place on the infamous BR-230.

It didn’t seem so bad. My first ride on the Trans-Amazonian Highway was with a woman from Belém driving a small, two-wheel drive Fiat. I asked her, wouldn’t she get stuck? She gave me a look and said of course not.

What Wikipedia fails to mention is that, for the past two years the Brazilian government has been hard at work paving the TAH. While it is indeed mostly dirt, the massive quagmires I had seen on the Internet had been mostly filled in, and there were even little 5 or ten kilometre stretches of pavement here and there. To be honest, I had been on worse roads in Bolivia – even the back roads outside Belém were worse than this. I would make it to my destination in no time!

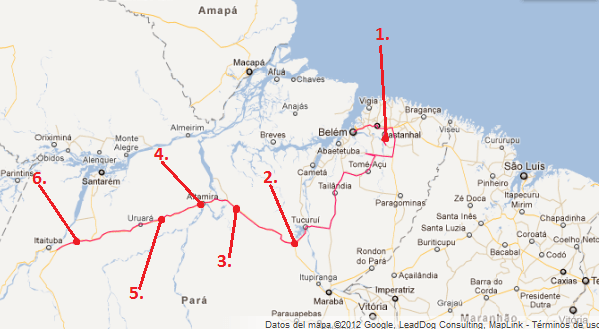

Speaking of destinations…the decision on exactly where to start my balsa rafting adventure had been a difficult one to make, and I changed my mind several times over the course of the four additional days I spent in Belém after returning to South America. The first, and most obvious choice, was Santarém – a medium-to-large city located at the convergence of the sapphire waters of the Rio Tapajós and the brown, murky depths of the Amazon itself. It’s a straight, 600-mile shot downriver to Macapá. But I wanted a bit more; I didn’t just want the Amazon. I wanted tributaries and narrow little rivers and head hunters.

Further scrutiny of my map revealed a perhaps more audacious route starting in the city of Altamira on the banks of the Xingu river, around 1.000 km west of Belém. In spite of the tempting adventure the banks of the Xingu offered, this destination was ultimately dropped due to the fact that the Xingu flows almost directly into the mouth of the Amazon – a complex and confusing maze of islands and swamps that would be extremely difficult to transverse on a raft for the 200 additional miles to Macapá, going more or less cross-current on a man-powered vessel through the mouth of a river which discharges more water in a month than all the rivers in Europe put together in ten years. Not to mention the fact I possessed no navigational charts of the area.

Finally, I settled on Itaituba, a medium sized city situated in the sweltering Tapajós valley along the banks of the river of the same name. From Itaituba I would have about 300 miles to navigate down the deep, wide Amazonian tributary to Santarém and the Amazon itself. For a solid week, Itaituba was a green light – good to go. I told everyone in Belém that I would be building a raft in Itaituba and sailing it down the Tapajós and Amazon to the ocean, to which they responded with the dubious looks I’ve become so accustomed to seeing on the faces of nearly everyone I meet when I tell them about almost anything I have done or plan on doing.

However, as I bumped along the BR-230 with the woman from Belém, I got to squinting at my map – something I often do – and saw that there was what seemed to be a perfectly viable destination even further south of Itaituba – a town which lay tantalizingly in wait down a dirt road known as the “Rodoviária do Ouro” – the gold highway.

At the end of the Rodoviária do Ouro, along the banks of a river I had never heard of, lay Mundico Coelho – a hard-knuckled, frontier town on the edge of the Amazon Rainforest’s richest and most productive gold mines. The Crepori was my river; it was small and wound its way around blank areas of the map for a few hundred kilometres before flowing into the Tapajós. It looked narrow and full of head hunters. What could possibly be a greater adventure than this?

Well, I thought helplessly, go big or go home.

New destination: Mundico Coelho.

———————————————————–

The woman from Belém dropped me off a few hours later in Amapú, a couple hundred kilometres southwest of Altamira . There was only about an hour of daylight left, but I stayed out hitchhiking as the light bled from the sky, hoping to inch just a little bit further down the road before going to bed. This turned out to be a good move on my part, for just as the stars were beginning to come out a beat-up Ford pickup stopped and brought tidings of a ranch and free range hammocking spots.

“I’ll take you to a house where one of my cowboys lives,” said the rancher. “I’ll let him know you’ll be camping out there tonight.”

We soon pulled up to the fazenda, as ranches are called here in Brazil. The only occupants in the house when I arrived were a woman, and a young girl with long black hair around three or four years of age. I introduced myself, and the woman smiled and told me I could set up wherever I liked.

I had hung my hammock and mosquito netting between a few açaí palms, and was just getting ready to put the tarp up when the man of the house galloped up on horseback, returning from his day out with the cows. He came up and introduced himself, shaking my hand, and said I should put the hammock up under the porch in case it rained, and to let his wife know when I wanted some dinner. Now, normally I would have delighted in setting up under the porch where there was a roof, but another new piece of gear I picked up in the US was a tarp/poncho, and I was still working out some of the rain-proofing kinks.

While camping out one night in a cow pasture somewhere near Tome Açu (a town on the back roads near Belém), I had been faced with a night of violent thunderstorms and heavy rain. The tarp had not performed well, due to the fact that it was also a poncho and as the rain fell, water gathered in the hood (which I had tied off). Eventually, the weight of the accumulated water started leaking through. I figured the problem could be solved if I tied the hood up to an additional line strung above the tarp, thus creating a dome and making it impossible for water to leak in, as well as not tying the hood inversely shut. This system, while fundamentally sound, still lacked field-testing, and I had been hoping to get a rainy night out on the ranch to reveal any further flaws for correction.

Still, I had trouble explaining to the cowboy that I wanted to sleep in the rain that night, and in the end I gave in to his imploring and moved the hammock to the porch. The tarp would have to be tested another night.

———————————————————————————–

As I ate my meal of rice, meat, and farinha (a sort of powdered root that the people of Pará put on almost everything), I enjoyed the company of my hosts as we sat together on the porch of the Amazonian fazenda. As usual I was being treated very well and my hosts were pleasant. I watched the little girl sing and dance to Michael Telho’s Si Eu Te Pego (which is inarguably the most popular song in Brazil at the moment). Perhaps the most amusing thing about the whole performance was the fact that she didn’t dance like an ordinary little girl – she danced like a Brazilian woman. This, for anybody who hasn’t seen a Brazilian woman dance to sertaneja music, is an awfully erotic dance. Seeing a little girl dance like that is positively hilarious – but at the same time makes you feel a little bit uncomfortable – like, you shouldn’t be laughing at this, you perv.

As the night progressed, the cowboy seemed to be getting inexplicably drunk – I say inexplicably because I did not once see him with a drink in his hand. However, this mystery was solved when I noticed him taking frequent trips into the house and emerging each time just a little bit tipsier. After only an hour, the cowboy had progressed to the stage of drunkenness which can best be described as “sloppy.” His wife began commenting that maybe he shouldn’t be drinking so much, to which he responded with words that, when translated, come out to basically “shut up, woman.”

Around ten the woman and little girl headed off to bed, after which the cowboy started positively blasting vaquiero music from one huge, lone speaker he had set up on the porch.

“Hey!” he slurred at me over the music, “you want some cachaça?”

“Some what?” I shouted back.

“Cachaça!” he bellowed.

“Oh,” I said. “Sure, I guess!”

“Hang on!” the cowboy hollered, and disappeared into the house.

Cachaça, for those of you who don’t know, is liquor made from distilled sugar-cane juice. It’s mostly produced in Brazil, where 1.5 billion liters (390 million gallons) are consumed annually. Tonight, it seemed, my cowboy friend was doing his patriotic duty by contributing a couple more bottles to Brazil’s boozer statistics. He emerged a few minutes later empty handed, glanced nervously into the house – and then pulled a cup full almost to the brim out of the front pocket of his button-up shirt.

“Drink it quick, don’t let my wife see!” he yelled, motioning for me to take it all in one go. I gazed at the cup apprehensively. That was a lot of cachaça. I sniffed it, and gagged slightly; the stuff smelled like pure rubbing alcohol. With that drink I could have probably euthanized a bear, and still had some leftover to amputate someone’s leg and perform open-heart surgery.

“What kind of cachaça is this?” I asked the cowboy.

“My cachaça!” he said, grinning. “I made it!”

Moonshine, I thought, not really very surprised. Wonderful. Steeling myself, I tipped back the glass and filled my mouth with hooch. Immediately the overpowering alcohol smell flooded my nostrils, and my lips and gums tingled in protest. I sloshed it around in my mouth a couple of times as my stomach begged me not to swallow – but swallow I did. Three times, each gulp more appalling then the last, and then the glass was empty and little green stars were floating around the tops of my eyes. The cowboy grinned and laughed as an involuntary shudder ran deep down my spine and reverberated up and down my body a couple of times. He grabbed the cup and disappeared back into the house, returning moments later with the bottle, which had just a little bit of cachaça left in the bottom – along with a bunch of small fruits fermenting away that had apparently been nuked in the distiller for the sake of cheap, toxic booze.

He shared moonshine, I shared tobacco. He was very much excited about the whole corncob pipe affair.

“This was full when I came home today,” he slurred, chuckling, and finished off the last of it with a gulp.

I belived him.

—————————————————————-

Around midnight I was ready for bed, but the cowboy sure wasn’t. I retired to my hammock and said good night as the ranch hand dozed in his chair and kept the music blasting. After awhile, I saw him through my mosquito netting vanishing into the house, and wondered why he didn’t turn that damn music off before heading inside. I lay in my hammock for a bit longer before deciding the cowboy had probably passed out in there somewhere, and getting up to shut off the speaker. I had just gotten my netting untied when the cowboy, followed seconds later by his wife and daughter, came bursting out of the house. The man was angry and shouting, and the woman and the girl were crying.

The woman sat down in a chair next to me as the cowboy mounted his horse and galloped off down the road.

“He hit me!” she sobbed, pointing to her cheek. “Right here, in my face!” A bruise was beginning to form under her eye.

I was rather at a loss for what to do. “I’m…erm…sorry,” I said lamely, and patted her on the shoulder.

“I don’t deserve to be treated this way!” she bawled, and spent the next ten minutes howling and basically repeating herself. I felt horrible for her, and wished I could help, or do something about it. But what are you supposed to do in a situation like that? Call the police, who are 25 km away in Amapú and probably don’t give a hoot anyways? And who calls the police on their hosts? Anyways, I don’t think the house even had a telephone line.

The cowboy came careening back on horseback a few minutes later, followed shortly afterwards by a concerned neighbor. The neighbor talked with the cowboy, trying to get him to calm down, while the woman kept crying and spewing long strings of words I couldn’t understand. The girl sat on the ground and blubbered, tears running tracks down her dirty little face while mosquitoes buzzed around her hair. The men shouted and waved their hands, the woman moaned and held her head, all the dogs on the ranch were barking at the same time, chickens were sprinting frantically around the yard and bumping into each other – and that damn music, it just kept on playing.

Yes, ladies and gentleman, I had myself a good ole fashioned, swashbuckling cowboy night out there at the Amazonian fazenda – an evening of loud music, spittin’ and hollerin’, bathtub moonshine, and wife-beatin’. Guess the country folk act pretty much the same no matter where you go. The whole thing could have just as easily been a scene from my neighbour Raymond’s house back in East Texas.

Oh, the wonders of world travel…yee-haw…

——————————————————

The next morning I awoke to an empty home. I looked at my watch; 0800. The only sounds I heard were the buzzing of flies and an old sow, shuffling around in the yard. I decided to give it a bit longer, and wait and see if anybody showed up. I dozed and watched the flies crawl around on my mosquito netting and the chickens pecking at some old rice on the ground.

0847. A small green lizard ate four flies and an assassin bug from his perch up by the ceiling. I applauded after each kill.

0849. Sleep.

0923. A rooster chased a grasshopper for ten minutes before losing it in the bushes. To nullify his defeat at the antenna of a lowly arthropod, he screwed two hens and crowed loudly.

0939. Killed two swollen female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes who had found a tiny hole in my netting somewhere, and spent the next ten minutes imagining symptoms of dengue.

0950. Sleep.

1000. Awoke from a half-dream, where I lived in a world where everybody had giant wristwatches where their heads should be.

1009. The old sow ventured onto the porch and pooped a couple of times. All chickens and flies in the immediate vicinity had a field day.

1018. A large, orange and yellow dragonfly landed on my mosquito netting and stared unnervingly at me for several minutes, probably wondering if I had any more Aedes aegypti hiding under my hammock.

1021. Stared at the wooden ceiling of the porch until I began to see faces in the grain.

1022. Spotted Jerry Seinfeld in the wood, and began thinking about bees.

1023. Had a brief craving for honey.

1024. Started thinking about that time when I was ten and ate an entire honeycomb at my Uncle George’s house in Missouri, comb and all. Remembered puking sometime later that day and fearing honey ever since.

1025. Remembered that I also hated red velvet cake, on account of I had puked it up once at my Mámá’s house while I had the flu.

1026. Went over the history of the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic in my head. Remembered the only place in the world with no reported cases had been a nearby island in the Amazon delta.

1030. Resumed imagining symptoms of dengue.

At this point the house was still empty, and I assumed that the previous night’s events had caused a break in day to day activities, and that everybody had vacated the home for the time being. Not wanting to waste anymore daylight, I packed up my hammock and bathed briefly in the outdoor shower. I was just about to leave when I heard the sound of hooves on dirt, and the cowboy came galloping up in rubber boots.

I waved. “Where you been?”

“Working,” he said. “Have you seen my wife?”

“Não,” I said, shaking my head. “I thought she was with you.”

“Ni pensar. Did you see her go anywhere?”

“I woke up alone.”

“Hm,” he said, scratching his head. “She probably went over to her Dad’s house in Amapú.”

“You think so?”

“Yeah, almost positive,” he said, sighing. He noticed my pack sitting on a chair nearby, loaded up and ready to go. “You leaving?”

I nodded. “I was planning on it. Didn’t know where everybody was.”

“Aw, but you should stay a little longer. Relax, I’ll bring you some lunch from town.”

Well…I didn’t need a repeat of last night. I could have gotten more sleep in the rain. Still, it was already almost noon, and perhaps the fazenda had more to offer yet…

“What the hell,” I said. “Why not.”

—————————————————————

I killed an easy afternoon opening palm nuts I found nearby and nibbling at them. The palm nut is a tough nut to crack – pun intended – but the tasty yielding fruit is well worth the effort. For those interested, you’ll need either an axe or sledgehammer and a machete to get them open. I took note of the plant’s features and memorized them for future reference. This was perhaps unnecessary, as they are a distinctive palm which seemed to be practically the only large tree growing in the cleared jungle around the cow pastures – along with patches of açaí and balsa wood.

Balsa wood, I was happy to note, was extremely prevalent almost everywhere I looked. Smaller specimens (less than 20 feet) dotted the roadside, and were easy to identify by their distinctive broad leaves and pink flowers. A walk into the jungle revealed many more specimens of impressive proportions – some as tall as 120 feet, and with trunks easily 5 feet in diameter. This was good news, as balsa was what I intended to use for the construction of my raft, it being almost impossibly perfect for the job, viz., it’s filled with air pockets and floats like nobody’s business. The word “balsa” means “raft” in both Spanish and Portuguese for this reason, so that the direct translation of arvol da balsa is “raft tree.” I would be a fool to use anything else!

Curious as to the properties of live balsa wood, I set out into the cow pasture and cut a small balsa tree about fifteen feet high for research purposes. My Gerber hatchet sank easily into the light, moist wood, which I noticed was soft and very malleable. I found the tree extremely easy to fall, the whole affair taking less than two minutes.

One discomfort I ran into while cutting was the presence of many fire ants in the tree, which make a habit of feeding on the nectar of the blooming flowers up top. These ants attacked viciously as I chopped, true to the instinct of the common fire ant – but I found that after cutting the top boughs where the flowers were, the ants abandoned the trunk after just five or so minutes, leaving me free to drag it back to the homestead and perform my investigative surgery.

I dissected the balsa and noted the gigantic air pockets running through the heart of the plant, some filled with dark, turpentine water. (Survival note: Balsa wood contains water. Probably not potable without purification). The pockets were so massive I wondered how the tree even stayed up during thunderstorms. Still, the boughs were strong, and would surely make an excellent raft in greater proportions.

——————————————————

Later that afternoon the cowboy returned with some lunch, and invited me across the road to a friend’s house for a bit of socializing. Socializing in rural Brazil is apparently not complete without copious amounts of mostly homemade alcohol. In today’s case, the hooch consisted of two massive jugs of sweet wine – something I felt was a considerable improvement from the bear tranquilizer the night before. The cowboy set off on horseback while I followed behind on foot to the homestead across the road, about 1 km away.

We sat in the late afternoon sunlight and sipped the wine, talking about manly things and comparing machetes. I was fresh from my little expedition to cut the blasa tree, which had been situated in some very high and abrasive elephant grass out in the cow pasture, and as a result was still suited up in my jungle gear. This consists of camo pants, aviator boots, leather gloves, heavy brush pants, long-sleeves, hatchet, and of course, machete. Of particular interest to the group was the old knife sharpener which I had brought back from the US, which has the capability to put a keen edge on the blade of a machete in just a few seconds. I passed it around the group, and three or four rusty machetes were made razor sharp before being blunted again on pile of pine nuts.

We traded tobaccos, myself giving up a few pinches of my pipe tobacco for cigarette-rolling, and receiving in turn a pouch of moist, black maratá tobacco, which most of the gauchos and local people smoke in cigarettes rolled from corn husks or notebook paper. It left a thick, black cake in the chamber of my pipe that took twenty minutes to scrape out.

The small, two room dwelling where this family lived housed the rancher I had met before, his wife, two young sons, and teenage daughter, who herself had a small child of about one year of age. As night fell we ran a dangerous-looking conglomeration of electrical cords outside to where we sat, and hung a bare light bulb off one of the roof struts to provide light for the evening’s festivities. The cowboy disappeared back to his house and came back half an hour later lugging his giant speaker and DVD player, to which we rigged electricity in a manner that was perhaps the greatest fire/electrocution hazard I had ever seen. Then the music was blasting again, and more jugs of wine materialized from somewhere as tongues were loosened and barefoot children ran about, screaming and swinging precariously off overhanging palm fronds.

The children were absolutely fascinated with my camera (yes, another thing I got from the USA), so I spent a few minutes teaching them how to use it, and subsequently turned them loose. I got the camera back the next day with 1.328 photos of mostly people’s feet and the television screen showing some soap opera or another – though there were a few keepers and a funny video of them running around with the baby and saying things like “Câmera, ação!”

We built a small fire, and as I was chopping up boards for kindling I saw the cowboy and the rancher dragging a pig bodily into the light. It squealed in that hedonistic way pigs do as the two men cut its throat out and hung the body up from the roof struts, so that the blood gushed freely out of the holes in the neck and accumulated in a stagnant pool below. The fatted pig had been slaughtered, and the feast was soon to come.

I was curious as to how we would go about butchering the hog. In Bolivia, pigs were skinned and quartered, much like we do back in the US, but here a different technique would be used. Instead of skinning the animal, we simply removed the hair. This was accomplished by boiling huge pots of water over the fire, then subsequently pouring it over the carcass. This caused the skin to crinkle up and sizzle, whereupon we would scrape at it with the edges of our knives, thereby removing the hair – much like scaling a fish, in fact. We did this to every part of the body, even the ears and face, which would all be eaten at one time or another.

After removing all the hair the swine was gutted – which is pretty self-explanatory, and was something that I had done many times before, both to swine and deer. We saved the heart (the best part) and cooked it over the fire, taking a quick break to eat it before continuing with the butchering process, which at this point just consisted of quartering the animal with our machetes.

The pig was cut into nine sections: two front legs and shoulders, two back legs and haunches, two racks of ribs, two strips of spine and backstrap, and the head. The ribs were taken inside and stored in the refrigerator, while we set about grilling one of the haunches over the fire and preparing the rest of the meat for smoking.

This was done by cutting as much of the meat as possible off the bone and into thin strips about three inches long by one inch wide. Between the four men present, we managed to debone most of the meat in about an hour. By this time the haunches were ready, and the women came out with plates of rice and mashed banana, to which we added the sizzling haunches. After filling our plates we put some of the meat out to smoke over the fire (with the exception of the skin, which was taken inside and fried into what we call back in Texas “cracklins”).

We ate, drank, and were merry. The dogs descended upon us and begged, hanging around by the drying pool of blood nearby and lapping at it occasionally. By the time we finished our meal it was time to rotate the meat, which we did as the women came through and collected the bones, bringing them inside to boil for broth.

We drank the night away, the cowboy expressing remorse that his wife was in Amapú and the rancher expressing hopes of this pig lasting them a good week and a half after they got some more rice. The children galloped through, snapping pictures of everything and chasing the dogs around. The women giggled amongst themselved from their chairs and hacked open Brazil nuts with machetes.

And that vaquiero music; it played on from the cowboy’s speakers, blasting through the jungle and rattling mangos and goiabas like an invisible percussionist, enveloping us as the cantor sang what I felt were appropriate words:

Eu sou sertão sofrido

Mas de um povo hospitaleiro

Que faz da vida a cantiga

Briquitando o ano inteiro

Um catrumano valente

Que sobrevive contente

No aboio do vaquiero

——————————————————–

I vaguely remembered learning to dance to vaquiero music with the rancher’s daughter and laughing far too loudly for most of the evening. There were some armadillos in there somewhere, too. The last thing I did was hang my hammock up in the rancher’s living room (I had to make a trek to the cowboy’s house to retrieve it…not surisingly he had locked his keys in the house, and I ended up climbing in through a window), before sweet, welcome sleep enveloped me and I knew no more.

————————————————————

The next morning we rolled groggily out of our hammocks, holding our heads in our hands and drinking coffee. I helped the rancher set out the previous night’s smoked meat to dry in the sun.

“You’re pretty interested in animal processing, huh?” he remarked as we salted the meat and draped it over the clothesline.

“Well, it’s not animal processing in particular,” I said. “Just different ways to do things I already know how to do. Plus, you never know – I might have to good fortune to kill an animal on the raft trip, and the local way of slaughter and meat preservation is usually the best way.”

He nodded. “Is that how you plan on feeding yourself on the trip? Hunting?”

“Oh, no. I was hoping for mostly fish and fruits. That’s one of the reasons I stuck around at the vaqueiro’s place yesterday. I was doing some independent research on plants.” Cutting down a balsa tree and bashing open pine nuts, I didn’t add.

“Well, if you want you can stick around here for a few days. I can teach you many things about plants in Amazonia.”

I stopped salting the strip of meat in my hand. “Really? You wouldn’t mind?”

“Of course not, gringo!” He patted me on the shoulder, a bit of salt flaking off his hand and cascading down my shirt. “You’re my friend, I am happy to help my friend. Anyways, we have so much pig meat to eat, you know?”

I did know. I grinned. “Well, I guess I’ll stay, then!”

“Very good!” The rancher clapped his hands with delight. “Um americano, in my house! This calls for more wine…!”

—————————————————

“These,” said Igor (for that was the rancher’s name) “are known as goiaba. They are ripe to eat when they have turned yellow.”

We were out in the jungle surrounding my friend’s new house identifying fruits and edible plants, accompanied by his two sons. The goiaba was yellow, about the size of a baseball, and had a fleshy red interior filled with hard seeds. It had a sharp, tangy flavour that was not unpleasant., though the seeds were very hard, and I found it easier just to swallow them whole rather than going through the trouble of chewing them up. They grew from a tree that looked vaguely like a lemon tree.

We continued our walk, and soon came to a towering tree with many small, glassy, shiny leaves. Up top were a pair of enormous, spiky fruits. They looked like Asian durians, and Igor gave me a name for them that I could not remember. (Thanks to my freind Amit Evron for reminding me of the name: jaca) Still, they were extremely easy to identify, and Igor told me to climb up there and hack a couple of them down with my machete. I did so, but as I was just about to reach the fruits I heard the sound of a million angry wings buzzing.

“Cut it and come on down!” shouted Igor at me from below. “There’s bees up that tree!” I swung my machete and the spiky masses sank to the ground, landing on the soft, leaf littered jungle floor with a dense plunk.

The buzzing was louder now, and I felt a hundred tiny wings and legs wriggling around in my hair and on every exposed bit of skin. I slid down the tree as fast as I could, and dropped the last six feet. Igor and his sons were busy covering their heads up with their shirts and running away. I followed, the bees hot on our tail.

The insects were everywhere, and I waited, cringing, for the feel of their stingers. It never came. Instead they just bombarded us, focusing primarily on our hair, burrowing down as deep as they could until they reached the scalp, where they would bite and then die shortly afterward. We ran back to the house with our fruits, a good number of bees still following us.

At least they were not stinging bees, I thought, picking one out of my hair, where I would continue to find dead bees for the next three days.

We left the spiky fruits by the door – along with our haul of goiaba – and sat down for our dinner of rice and swine ribs, while watching the soap opera Fina Estampa.

———————————————-

Days at Igor’s house were generally quite lazy, and there was always someone hacking away at a Brazil nut somewhere. One of the many things I learned at the ranch was how to open a Brazil nut with a machete in less than twenty seconds without losing a finger (though I can assure you there were numerous close calls, and I bear several scars on my left index finger to prove it).

Igor’s daughter, who seemed to be around sixteen, had the habit of nursing her baby quite without any shirt on. The fact that she was far from ugly and that if she wore a blue shirt, it would have been a huge blue shirt, was not lost on me. I spent many hours trying as hard as I could to look at anything but the great, massive breasts with a baby hanging off one end sitting right there in front of me, and tugging at my hypothetical collar. She took no notice of this, of course, and relentlessly bombarded me with questions about my computer and camera. I taught her how to make drawings on Microsoft Paint, and that seemed to occupy the giant breasts long enough for me to escape into the jungle with Igor and the boys to hunt for açaí.

Açaí is one of the major staples of the Amazon. It is a hard, purple berry which grows at the top of a tall and slender palm with droopy, feather-like leaves. While the palms are literally everywhere, finding one with ripe berries takes a little looking around.

“Ah, there’s one over there!” said Igor’s son excitedly, pointing. The palm was in the centre of a grove that was currently flooded with about two feet of water. We waded into the mire and prepared to harvest the berries.

In order to harvest açaí, one must do a little bit of climbing. The açaí palms are never very thick but can sometimes grow to about 50 or 60 feet in height – and the berries are at the very top. Here in this grove there were three or four trees with ripe berries, so each of us picked one and shimmied on up. It was like climbing the fireman’s pole at the playground in elementary school – only the pole was a 30-foot palm tree with the occasional fire ant patrolling up and down it, and you were carrying a machete. Once you got to the top you would hack away at the little branch the berries grew on until it fell down, then slide gratefully back to earth, your arms and legs on fire with the strain of holding your whole self at the top of the palm.

The first tree was easy. We plucked the berries off the branches and deposited them into our five gallon bucket, as well as mopping up the other ripe berries that had fallen and were floating around in the bog. Then we set out to find more, which we did easily.

The second tree was more difficult, and I found myself very much out of breath by the time I got to the top of the palm and had cut down the berries. The third tree was even harder, and stretched up to at least fifty feet above the ground, and my legs burned in agony as I clamped them down onto the trunk to free my hands for machete work. By the time I got to the top of the fourth tree I nearly fell out, I was so exhausted by that time.

My hosts, at least, were equally tired. I had feared that they would be shimmying up açaí like chimps without even breaking a sweat, and there I would be, about to puke up my cracklins into the swamp. But by the end of the day we were all thoroughly exhausted and ready to return home. Our yield had come out to three buckets full of berries.

Next step: processing.

———————————————

Açaí is not generally eaten in its berry form, since it’s so hard, and is usually consumed in juice form. There is a simple process to transform the berries into the purple goop I had become accustomed to eating in Belém – simple, but like most things in the jungle, involving plenty of elbow grease.

First we soaked the berries in huge pots of warm water for an hour or two. Then, with the help of the entire family, they were pulverized in buckets with the use of a sturdy stick. The smack smack sound of açaí mashing echoed throughout the little house as we worked. Igor’s daughter, I noticed with relief, had put a shirt on. The thought of those giant breasts, bouncing along with the rhythm of the pounding…I would have had no focus whatsoever.

After mashing for a good ten minutes, we added a little bit of water and mashed some more. Then we mixed all the berries together into one big pot and took out as many as we could, leaving behind a considerable amount of juice and pulp in the big pan. After that we re-mashed the remaining berries, added more water, and mashed them some more.

The final step was to mix all the juice together and filter out the skins using a strainer. The end result was a purplish-brown liquid that was the classic açaí. Technically it was ready to eat now, but we let it sit in the refrigerator for a little while, which made the açaí solidify a bit and turn a darker purple. That evening we had delicious cups of açaí, mixed with sugar and farinha.

Straight from the jungle to you, I thought contentedly, stirring in more farinha and paying attention to Fina Estampa for the first time ever.

———————————————————–

Over the next few days, Igor and his sons taught me to identify many different types of edible fruits and plants common in the Amazon, something I was careful to note and remember – for living off flora will be a great part of the raft expedition. Gladly I report to you that the jungle is just teeming with food – and to be frank I believe you would have to be quite stupid to starve to death in the Amazon. Fruits are everywhere, and they’re oftentimes large, with just one of them able to easily sustain you for a day. Though I understand that further in the jungle, where everything occurs on a random basis, it may be difficult to find some of these fruits. Still, apart from fruits, bugs are everywhere you look, with the underside of every fallen tree and rotting log home to at least one fat, edible grubworm.

After awhile I began feeling like it was time to move on and start putting these new skills into practice already, so following four days at his ranch I let Igor know that I was headed out. I got my pack and other items back from the cowboy’s house, where they had been since I first came to the fazendas, and prepared for departure.

“Be careful in creporição,” said Igor, referring to the mining frontier where I was headed. “Lots of outsiders out there working in those mines. Shady characters, desperate folk. They’ll kill you if you’re not careful.”

I doubted this, but assured Igor I would watch my back. The little fazenda disappeared behind me as a light rain fell from the grey February sky. The mud of the Trans-Amazonian Highway caked itself onto my aviator boots, making each step unnaturally heavy as I slipped into fantasies of what the legendary-sounding creporição must be like. I pictured something like “San Fransisco, 1825,” but with jungle.

Soon a pickup stopped for my thumb, slamming on the breaks and skidding along the muddy road for ten feet before coming to a stop. Off I went to Altamira, one step closer to the enigmatic rodoviária do ouro.

——————————————————–

After a ferry across the wild-looking Xingu River, a thirty minute drive brought us to the city of Altamira, a medium sized town situated basically in the middle of nowhere. I took this opportunity to make a post on this blog about the raft trip (the post preceding this one), as I was unsure if I would have any internet for the following weeks leading up to my departure from the creporição.

After being kicked out of a promising spot by a security guard, I pitched my tent in Altamira next to a university. The next day I planned to go to the hospital and see about obtaining some medicines for the upcoming trip – namely, quinine and antibiotics.

I was not totally broke; I had about R$100 on me, which was a combination of the leftover pesos I had changed at the airport in Rio and the R$50 I made selling the old laptop I brought back from the US on the streets of Belém. I still needed a few additional supplies for the journey, namely, rice and a large pot for boiling water. These, I hoped, would not run me too much money, and I hoped to have enough to get those items and the quinine from the hospital in Altamira.

When I got to the hospital and started yammering on about quinino, I was pointed to the malaria ward, where I sat in a plastic chair next to a sallow-looking man with circles under his eyes. He leaned over to me and said,

“Which strain of malaria do you have?”

“Hm?” I said, distracted. “Oh, I don’t have malaria, I’m just looking for medicines.”

“Oh,” he said, and sank back into his chair, giving me a strange look.

The nurse behind the table on the other side of the room called me up. “Have you gotten your finger pricked, sir?” she said tiredly.

“Um, no,” I said, whereupon she dug around in her lab coat and extracted a little needle-like device.

“All right, hold out your finger,” she clucked, pushing a little button on the device that seemed to arm it.

“Uh, no, I don’t need to get my finger pricked,” I said, keeping my hands in my pockets.

“Sir, we need to find out what kind of malaria you have,” said the nurse sternly.

“No, you don’t understand,” I said. “I don’t have malaria!”

The entire room seemed unnaturally silent after that last sentence, and it felt like everybody was sort of staring at me. I felt like I was at an NA meeting, and I had just said the words, “Hi, my name is Patrick, and – well, actually I’m not really an addict. I’m just here because of a court order.” I half expected the nurse to stand up, point at my chest and shout “Denial! The first step is admitting that you have malaria!”

Instead, she said, “Okay…so what are you doing here, then?”

“Well, I’m headed far out into the jungle, and would like quinine, antibiotics, and other preventative medicines.”

“Heading into the jungle,” she repeated. Sighing, the nurse reluctantly disarmed her finger pricking device and told me to wait a moment. She vanished out the back door, while I rocked back and forth on the balls of my feet, feeling the sallow-faced malaria patient’s eyes staring at me from the plastic chair in the corner.

The nurse came back several minutes later with a tall man who introduced himself as “Dr. Jorge, malaria specialist.” I shook his outstretched hand and we walked back to his office.

“Now, what can I do for you?” said Dr. Jorge, sitting down next to his microscope.

“I want quinine,” I said matter-of-factly, and explained to Dr. Jorge my plans of rafting along the Crepori river.

“Hm,” he said, drumming his fingers on the table. “Interesting. Well Patrick, let me tell you something. I have been to creporição, and the river you are heading down is not as isolated as you may think. There are pockets of both mining and native settlements along the Crepori, and we like to make sure we have a malaria laboratory in every community where there are more than five or ten families present.”

“Hm,” I said. “Interesting.”

“The point is,” the doctor went on, “you will probably not need any medicines we can give you, since you will be able to seek help at one of our labs there, should you fall ill. And anyhow, there are rules that prevent me from being able to give you medicines if you do not actually have malaria.”

“How come?” I asked, confused. “Travellers take preventative malaria medicine all the time.”

“Yes, but what you are talking about – medicine to take only on the occasion of you talking sick – we cannot simply give out. This is because we need to know specifically which strain of malaria you have, in order to treat you.”

“You can’t just give me simple quinine?” I inquired.

“We don’t have simple quinine. We have many diverse malaria medicines designed for specific malaria cases.”

“Hm,” I said. “But – well, for example: I become sick with malaria when not very close to one of your labs. Soon I am too weak to continue downriver to safety. Do you have something for that could keep the malaria at bay for long enough for me to find the energy to flee to safety?”

Dr. Jorge thought for a moment. “Perhaps. There is a drug called cloroquina. You can buy it in pharmacies. It will not cure malaria, but will keep you from becoming debilitated for long enough to seek help.”

“How much is it, more or less?”

Dr. Jorge stood up. “Wait here.” I waited. He returned a few minutes later with a few packets of pills. He handed them to me and said, “Don’t tell anybody I gave these to you. Take six pills the first day and four the next. This is two doses, which should be enough for you to get downriver.”

I took the pills reverently. “Thank you, Dr. Jorge. Also, I was wondering about antibiotics…?”

“What about antibiotics?” asked the doctor.

“Well, say I sustain an injury and want to stave off infection. Maybe some penicillin?”

Dr. Jorge sighed, smiled, and left the room, coming back several minutes later with 50 pills of sulfametoxazol trimetoprima. “These will work as both an antibiotic and temporary relief from dysentery – should you be unfortunate enough to fall victim to that.”

“Excellent!” I said. “I don’t know how to thank you.”

He waved his hand in the air. “It’s no problem.” He stood up. “We should go and see the director, he is more familiar with creporição than I am. He might be able to give you moregood information.”

“Cool, sounds perfect!” I said happily.

“Oh, but before we go…” Dr. Jorge took a digital camera out from his desk. “A photo? If I see you on Aló Brasil someday I will tell everybody that I know you.”

I laughed, and snapped a picture with him.

————————————————————

We went to see Dr. Vargeus, the director of the General Hospital of Altamira, in his office. Dr. Jorge told the director all about the adventure I had planned in creporição, to which the director laughed and called me insane. He was plump, jolly, and friendly, and was happy to dispense more advice about the Crepori River.

“That area has a lot of waterfalls,” he said. “You might find navigation kind of difficult.”

“Well, so long as I can always detect them before going over, I’ll be able to portage around,” I said.

He nodded, “Yes, you could. But it only takes one to sneak up on you, and then you’re done.”

I nodded. “True.”

We then talked about settlements along the Crepori and Tapajós. Dr. Varegus agreed with Dr. Jorge’s ascertation that the Crepori was inhabited mostly by isolated pockets of miners and natives.

“However, the Lower Tapajós is home to almost exclusively native peoples. There’s more than 50 tribes down in that area. Oh, and you should watch out for the Maranhão Grande rapids. They’re on the Tapajós about 25 km before São Luis, and go on for about 23 kilometres.”

“Noted,” I said. Twenty-three kilometres of rapids? This expedition was getting more ridiculous by the second…

————————————————————–

I lingered in the office for a few hours, chit chatting with my new doctor friends. They requested a concert on the harmonica, which I gave. Dr. Varegus paid me $10 reais afterwards and filmed the whole thing while chuckling lightly to himself. Then around noon I left.

“Good luck, and let us know if you succeed!” said Dr. Varegus, shaking my hand.

“And remember, the medicines I gave you will not cure malaria, they will only slow it down. If you fall ill go to one of our labs!” reminded Dr. Jorge.

“I’ll remember,” I assured him, and then I was gone, packing a first-aid kit containing a few potent new weapons that I hadn’t paid a dime for. The goodness of the world never ceases to amaze me.

Next stop: creporição.

—————————-

Getting out of Altamira wasn’t too difficult, though I did get a little lost looking for the other side of the Trans-Amazonian highway. I wondered how, by following the directions I had just received from a welder, this narrow dirt track filled with goats was going to take me back to the BR-230. But in Brazil directions from just about anybody are better than the Chilean’s “go up that way like, 5 or 9 blocks, and there’s a grocery store next to another grocery store and a tire shop. Turn left, then right, then go straight ahead when you see the old broken down pickup next to the chilote resturaunt.” The city spread uphill from the Xingu River, and I sweated and slipped along the muddy path, causing the goats to bleat irritably at me.

I made it to the BR gas station, where it had been recommended I hitchhike, but giving my good luck so far on the Trans-Amazonian highway I went here just for rest and some water. I noticed a few buses that had apparently been ex-city buses in São Paulo (I knew this because I could still see the place where the lettering saying “Cidade de São Paulo” had been) parked on the other side of the gas station. They had been converted into cross-country buses on the TAH, and the decal on the side read hilariously, “ASS Turismo.”

Now, I’m sure ASS is an acronym for something I don’t know – but then again it could mean exactly what it sounds like. This is Brazil, after all – a country widely known for being home to some of the finest asses in the world.

I began walking out of the BR and down the TAH, which reappeared on the top of the hill cresting over the Xingu River. I set up just on top of it, with a nice view of the wild-looking islands of the Xingu. I didn’t have much time to appreciate them, however, as a mid-sized pickup screeched to a halt and I hopped in the back.

Hitchhiking, I noticed, is extremely common on the Trans-Amazonian Highway – but, unlike the other heavily hitched areas I have passed (i.e., Patagonia, most of Argentina), all the hitchhikers here were unquestionably locals. In Brazil the busses are very expensive, and anyways, they pass pretty infrequently on the TAH, so hitchhiking is a common mode of transport from town to town. It helps that most (if not all) vehicles I saw west of Altamira were pickups of some kind or another, most of whom had no problem with stopping every ten minutes and throwing another hitchhiker or three in the back. The truck I was in drove me about 150 km to Medecilândia, and in that two hour ride we picked up no less than seven other hitchhikers.

On the TAH, it’s always best to be the first hitcher in the back of the truck – because that means you get to claim your spot in the front of the bed, where you can stand and hang on to the roll bars. This, I’m sure, sounds incredibly dangerous, (and it is), but it is infinitely more comfortable than sitting in the middle or back. The TAH, while it is undergoing paving operations, is still dirt, and dirt is not smooth. After fifteen minutes of sitting while bumping along at 50 kph, your ass wishes desperately that you had claimed those spots up front, where you can use your knees as shock absorbers.

Perhaps another reason hitchhiking is so popular on the TAH is the fact that hitching is infinitely faster than the bus. Not only do people pick you up no problem – they drive fast. In Altamira I had seen a bus leave for Medecilândia while I waiting at the gas station and laughing at the ASS Tourismo bus. I hadn’t been picked up until a good forty minutes after that, but an hour into my ride in the back of the pickup (with four new companions by my side who also realized that taking the bus was totally not cool), we zoomed by the public transportation, which was plodding along at 20 or 30 kph. I never saw it again.

When we arrived in Medecilândia, I noticed telltale dark clouds forming to the south, and headed to a nearby gas station to wait out the coming storm.

After more than a month in the Amazon during the rainy season, I’ve become adept at predicting when the rain will come and how long it will stick around. Dark, almost black clouds on the horizon that are sporadically separated by spaces of blue sky are heavy rain which will come, drench everything for twenty minutes to an hour, and then disperse, leaving the rest of the day mostly rain-free. Black clouds which blot everything else out on the horizon and make it hard to see trees more than 3 km distant are rain which will arrive quickly, rain very hard for 20 minutes to an hour, and then slack off to medium to light rain that sometimes lasts for days. Grey, flat clouds on the horizon mean it will probably rain lightly a few times during the day, but will mostly be just grey and dry. Huge thunderheads and high wind are signs of violent thunderstorms which bring impossibly heavy rain for at least an hour and truly impressive lightning shows.

Of course, there are the times when you just don’t see the rain coming. One minute there’s high stratus clouds up there with the airliners, next all hell has broken loose, and you’re seeing cloud-to-cloud lightning that streaks across ten kilometres of sky and has seventeen separate arms, while raindrops the size of cigarette lighters pound down on everything and the only sound you can hear is gut-blasting thunder and the low hiss of massive amounts of falling water. That’s the Amazon for you, I guess.

In the case of that afternoon in Medecilândia, the rain was the type that would rain hard and then disperse. I drank a coffee at the station and smoked my pipe as I watched the water cascade off the roof of the gas station and carve rivulets into the dirt parking lot. I thought about how futile it was to try and fight the power of water, noticing that the parking lot had been paved, probably as recently as ten years ago, but had already deteriorated to a state of ruin and massive potholes.

Right on schedule, the rain stopped twenty-five minutes later, and I slipped down through the mud back to the TAH, setting my pack and helmet bag down in some wet grass where it would not become as hopelessly muddy as my aviator boots currently were. The third truck that passed stopped, and I hopped in the back, leaving great globs of mud everywhere.

We drove for awhile down the highway, passing many of the typical wooden bridges that gap the numerous small streams winding through the jungle. These bridges, at first glance, look alarmingly flimsy, and ceatintly not capable of holding the weight of the 50-ton semi truck barreling towards it down the muddy hill at 40 kph – but every time those tough little bastards somehow find the strength to hold up against the weight. I was certain that at one point, some those bridges had to have broken and sent a truck plunging into the creek – for in many places I could see the rotting, skeletal remains of an old bridge paralleling the one we drove across. Some bridges looked truly on the point of collapse, with large sections of wood missing, having presumably broken off and sailed down the creek into the jungle.

Speaking of jungle, the road was starting to become more of just that. Between Novo Repartimento and Altamira, much of the land on either side of the highway had been cleared, giving me the impression at times that I was not in the jungle at all. Here, however, the road was a bit narrower, and the trees had encroached to right up on the road, flush with either side.

I gripped the wooden struts at the front of the truck as we barreled down another hill at impossible speeds, and suddenly we arrived to a tiny crossroads, with two small dirt tracks leading into the jungle on either side of the highway where there lay, according to a decomposing old wooden sign, three borracharias (tire shops), and a place to buy cachaça.

These were something that there were no shortages of on the Trans-Amazonian Highway: borracharias and cachaça. The humor in the fact that in Spanish, the word borracho means drunk was not lost on me – and it seemed that many of the tire shop attendants along the TAH were oftentimes borracho, anyways.

One of the TAH's many "borracharias." Note the typical recycled tractor tire being used as a road sign.

Here was where I got off, apparently, and I thanked the driver in the manner I had seen local hitchhikers doing, by waving and saying falló patrão, obrigado! (meaning literally, “OK, boss, thanks!)

I observed my surroundings; not much was going on at this crossroads, it seemed. There was a small bus stop nearby and that was about it. I did notice a large, 80 foot balsa across the road, and in a nearby tree I heard the distinctive cackling of a flock of green parrots.

If you want to kill a good hour of otherwise uneventful hitchhiking time in the jungle, listen to parrots talk to each other. Along with the distinctive squaaaaaak that you would expect to hear in the rainforest, a myrid of other sounds are also produced, viz, whistles, clicks, pops, shouts, cracks, whispers, honks, claps, raspberries, and numerous other sounds I cannot even begin to describe in words. My favourite were the raspberries; maybe it’s childish, but I got a good laugh out of hearing a bunch of parrots make unmistakable fart noises fifty feet up a Brazil nut tree in the middle of nowhere. It felt like they were putting on a show, ‘specially for me.

It was now getting dark, and I figured that I would probably be spending the night at this lonely little parrot crossroads somewhere between Medecilândia and Uruará. After seven, I officially retired for the evening, choosing the bus stop as the place to hang my hammock.

Finally, I had a chance to use my tarp again. The roof of the bus stop could scarcely be called a roof, as it had numerous gaping holes in it, so putting up the tarp was definitely called for. The posts were perfect for hammock hanging, and I spent a pleasant, industrious fifteen minutes rigging all my para-cord up for the tarp and mozzie netting. The end result, I’m proud to say, looked very spiffy and waterproof.

I then curled up in my hammock, tied up the netting, smoked a bowl out of my pipe, and went to sleep in a good mood, listening to the sounds of the parrots saying their goodnights (in Parrot, the words “good night” seemed to be a long whistle followed by an African-sounding click).

Life was good.

————————————————————————————

The next morning I awoke to the sounds of “good morning” in Parrot (click-whistle-pop-pop), and found two bloated brown female mosquitoes and one Aedes aegypti, making a mental note to find that blasted hole in my netting and sew it up. I killed the mosquitoes, as is customary, and broke down camp.

It had rained steadily throughout the night, and quite a lot of water had leaked in through the faulty roof of the bus stop, which had rolled easily off my tarp all night long, without me getting the least bit wet. Pleased that I had worked out the tarp issue, I started hitchhiking around 0710 in a good mood.

As I waited I played with a bunch of plants known in Pará simply as “Maria.” They appear to be normal, grass-like plants with the vague appearance of a fern – but when touched, they immediately close up their leaves and shrink down into the ground, becoming practically invisible. These I found fascinating, and spent many hours hitchhiking in Pará touching Marias, watching them droop and seemingly die before slowly, cautiously, opening back up and turning to face the sun.

Igor’s older son had explained to me the origins of the name “Maria,” through a little children’s limerick.

“Maria received news that her husband had died,” the boy had said, squatting by a patch of Maria, “and Maria became saaaaad.” As he said the word triste he brushed his hands against the Maria and it shrank away into the Earth.

A couple of women and a few children going in the other direction came out and started trying hitching a ride, but were having no luck. I was having little luck myself; I killed mosquitoes and watched fire ants come haul their bodies away, as I eavesdropped on the women across the street.

“There’s no way she’s telling the truth,” said one of them, shaking her head.

“Yeah, but what other explanation is there?” said the other one.

“I don’t know, but I don’t believe it. She’s always been a liar, what makes this time any different?”

The woman shrugged “I don’t know. I believe her.”

She scoffed. “Then you’re a fool.”

It was then a truck came rolling west and stopped for my thumb, and I never got to learn anything more about who “she” was and what the issue in question might have been. I rode in the truck for about ten clicks until it turned off into a fazenda, where I waited for about two hours.

I theorized that there were three types of trucks on the TAH: Semis going to Santarém or Mato Grosso, who rarely stop; 4X4’s usually heading from one medium-sized town to the next, who sometimes pick you up, but more often don’t; and beat-up old fazenda trucks, who almost always pick you up and are sometimes going just a few kilometres and sometimes are going hundreds of kilometres.

After a long wave of 4X4’s apparently all on the “don’t pick up the hitchhiker” wavelength, the welcome sound of a rickety old fazenda truck echoed up from the opposite hillside, and, as if wanting to help prove my theory that fazenda vehicles are the best, drove me for three hours all the way to Uruará.

It was on this ride that I tragically lost my hat. I was standing in the front, hanging on to the roll bars like usual, when suddenly we crested a hill and began veritably flying down the next one to the bottom. The wind whipping past my face was suddenly at hurricane force, and I felt a brief tug at my hat and suddenly it was gone! I let out a cry of dismay and saw my beloved cap tumbling, free of my unruly hair, down the empty dirt road.

What I should have done was pound desperately on the roof of the cab and get the driver to stop – but we were just bottoming out at the end of the hill and were careening madly up the next one, and it seemed stopping might trigger some deadly navigational errors on the part of the driver. I saw a motorcycle come up behind us and spot my hat, and I signaled desperately for him to pick it up and bring it back. He stopped, turned around, and appeared to be on his way to pick it up when we crested the top of the next hill and he disappeared from view.

When we got to the next flat area about three kilometres further up, I pounded on the roof of the cab and we came skidding to a halt. I jumped out and went over to the window.

“I lost my hat!” I said to the vaquiero driver. He looked at me and said,

“Mm! Too bad!”

“Yeah, but there’s a motorcycle that I saw turning around to go and get it, and I tried to signal for him to bring it back for me, and I think he’s coming back in a minute or two.” I scratched my head; it felt bare and stupid. “Any chance you could wait a second?” I asked hopefully.

The cowboy shrugged. “Sure,” he said, lighting a cigarette.

Relived, I thanked the driver and squinted expectantly down the road, hoping to see the moto headed down the hill with my cap. A minute went by. Then two. Then five. Still no moto.

“Hey friend, I think that moto driver stole your hat,” said the vaquiero from his window, blowing smoke at the rearview mirror.

“But –” I stammered, “but I made clear signs for him to bring it up here!”

“He stole your hat, man.”

“Argh!” I snorted. “That’s my hat!”

“Hey amigo, it’s just a hat.”

“Yeah, but you don’t understand! It’s my hat! A hat is a friend!”

“Well, I that moto driver stole your friend, then.”

I paced back and forth for a second. “All right, I’ll stay here and wait, just in case he comes back. Let me get my pack out of the back of your truck.”

“You’re gonna wait here?” said the driver incredulously. “But there’s nothing!” He gestured to the surrounding jungle.

“It’s my hat,” I said. “I’ve got to see if that motorcycle comes back.”

The driver shook his head. “Where you going, anyways?”

“Itaituba,” I said, still looking down the road for the phantom motorcycle driver, with my goddamn hat.

“That’s really far man, I’m going all the way to Uruará, that will take you about 200 km closer. You shouldn’t wait out here, you’ll be stuck forever.”

I sighed deeply. I knew he was right. But damnit, this was my hat we were talking about!

“You’re hat’s not coming back, amigo,” said the vaquiero. “Come on, let’s go to Uruará.”

I sighed. It had been fifteen minutes, and I knew the motorcycle wasn’t coming back. “All right, let’s go,” I said, hopping back into the bed of the old truck. The gaucho gunned the engine and we were off, and I cursed for a solid twenty minutes and felt like crap, because I hadn’t just lost my hat – I had lost my friend.

——————————————————————

As soon as we got to Uruará, I went immediately off in search of a new hat – because I sure as hell wasn’t going to tackle the Amazon in a balsa raft with my head un-covered. I had decided, while wallowing in self-pity in the back of the truck for the past three hours, that I would look for some sort of boonie cap – since there was no way I was finding a beret in a little town in northwestern Pará. Ni pensar, as they say in these parts.

I walked around for a bit, asking about hats, but only found a bunch of mediocre baseball caps. Finally I found a grocery store with an impressive selection of vaquiero cowboy hats, and a few types of boonie caps, in black, white, and camouflage.

“How much for the camoflauge one?” I asked the lady behind the counter.

She looked up from her magazine “25 reais,” she said.

I balked. “25 reais? For a hat?”

“It’s a good hat,” she said – but that’s what they all say. I examined it more closely and found that it was of decent quality, at least.

“I’ll give you ten,” I said flatly.

“No way,” said the lady. “Twenty, at least.”

“Eleven.”

“Ninteen.”

“Twelve.”

“Eighteen.”

“Twelve-fifty, or I’m out.”

She scrunched up her face. “Can’t you do fifteen? Help me out here, alemão.”

I looked around. “All right, fifteen – if you throw in some of those chocolate bars.”

She sighed and rolled her eyes. “All right, bargain-hunter. Take your chocolate.”

“Don’t mind if I do,” I said, handing her the money and putting the boonie cap on my head. “Appreciate it,” I said, waving as I left and opening a chocolate.

“Yeah, yeah…” said the lady, going back to her magazine.

——————————————————–

In Uruará I got free range of a buffet after inquiring for pasta cookage at one of the churrascarias, and was back on the road by one pm with a full stomach and a covered head. I was still sore about losing my beret, but hopefully this boonie cap would serve me faithfully for many miles and adventures to come.

I also found a truck that bore my name on the windshield, along with, ironically, a no hitchhiking decal in the corner.

From Uruará I got a ride in the back of an unloaded semi for what seemed like endless hours all the way to Rurópois, another two hundred kilometres down the road. It was a hot, dry day and the truck kicked up massive amounts of dust. As a result, when I got off late that afternoon I had transformed into the dark red colour of Amazonian dirt. This, however, didn’t stop me from getting another ride in Rurópolis to a town my map didn’t mention.

—————————————————-

In Brazil, town names can be divided into four categories:

- Genuine names (Belém, Goiâna, Palmas)

- Named after saints (São or Santa something or the other)

- Ending with –lândia (Uberlândia, Açaílândia, Cafélândia, Matelândia, Medecilândia)

- Ending with -polis (Florianópolis, Rurópolis, Pirópolis)

The suffixes –lândia and –polis are most common in small, rural areas, and he who examines a map of Brazil with find many, many places ending with one of those two endings. Tonight, it was a –polis (which, fun fact, is Greek for “city”) and it was called Divinópolis – meaning, I supposed, “Divine City.”

Divinópolis didn’t look so divine – in fact, it looked much the same as every other town I had passed on my recent westerly pilgrimage through the jungle; one dirt road went through the middle of town, flanked by a couple of restaurants and bars, a place marked “Terminal Rodoviário” for the bus, and a run-down old gas station rusting away in the corner of it all. A couple of smaller dirt roads threaded their way a few hundred metres into the town and soon petered out in jungle or swamp. Welcome to Divinópolis, apparently.

—————————————

I was busy eating my dinner, which I had gotten once again from a buffet after another pasta-cooking attempt, when the owner who had just authorized my free feeding came and sat down next to me. He was a burly man with brown teeth, wearing a colourful Carneval muscle shirt, swim trunks, and flip-flops.

“You’re a traveller,” he stated.

“I am,” I agreed, chewing on a hunk of meat.

“You’re sleeping tonight – where?”

I gestured vaguely towards the dusty, practically derelict Divinópolis gas station. “Over there, maybe in the troco de oleo.” (oil change shop)

He shook his head. “No, no, why would you sleep in the troco de oleo? You know what, I’ll invite you to my place. You have a hammock, right?”

“Sure I do.”

“Wonderful, you can hang it at my place, no problem, no worries. Tá boa?”

I smiled and nodded. “Tá boa.”

He patted me amiably on the back. “When you finish eating, come to the bar over there, I buy you a cachaça, all right?”

“Falló, okay. Thanks!” I said, and he went off to the bar.

———————————————–

Estefan was his name, and he pulled up a chair next to him and gestured a bit too forcefully for me to sit down. It was obvious he was already three or four cachaças into his Wednesday night. We talked about his town (pop. 127), and my travels.

“Three years, you’ve been travelling like this?” said Estefan with disbelief.

“Something like that.”

“I’ll be you’ll never remember me,” said the burly man, chuckling and refilling his glass.

I disagreed, and told him I always remembered everybody – especially those who had helped me.

“Naw, bullshit Patrick,” said Estefan, refilling my glass. “I’m just another face! You’ll forget me by tomorrow!”

I protested, but had to admit I could see where his reasoning came from. I knew I had in fact forgotten many kind faces over the years – faces of people who had helped me. It was a shame, I thought, that I couldn’t always vividly recall every kind gesture and benevolent smile that I’ve come across during these years as an aimless wanderer.